A detailed history of Preston: Part three

The Manor of Minsden from Domesday to the fifthteenth century

Lest we become obsessed with the domination of Preston by Temple Dinsley, it is time for a reminder

that the district around Preston was also governed by other manors. One such was Missenden or

Minsden.

Domesday reported that ‘King William holds Mendlesdene. It is assessed at 4 hides (around

480 acres). There island for 8 ploughs. In the demesne (the Lord’s holding) there are 2 hides

and 2½ virgates. A priest with 8 villeins and 2 cottars have 3 ploughs between them and there

could be 2 more. There are 6 serfs.

Meadowland there is sufficient for the livestock of the vill. There is woodland to feed 30 swine.

The manor belonged and still belongs to Hiz (Hitchin). Earl Harold held it.’

Thus, significantly, a priest lived at Minsden together with around thirty-eight other people in sixteen

homes. We might conclude that there was a church at Minsden in 1086 (although Bishop suggests

that Minsden Chapel was built in around 1300).

The manor comprised mainly of meadows and included a compact wooded area. Gerry Gingell

described it as ‘a very small hill-based community which struggled for survival up until the

seventeenth century.’

The hilltop of Minsden. The chapel is to the right of the copse

All that remains of Minsden is the ruined chapel of St Nicholas. It was a chapel of ease to St Mary’s at

Hitchin and served villagers from the village of Langley. As it lay near the pilgrims’ route of St Albans

Highway and being clearly visible from the road, perched on a hillside, it also attracted travelling

worshippers.

Did Preston people worship at Minsden? As we will see, there is no doubt that they attended services

there in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. However, from before Domesday, there had been a

religious house at Preston and the Templars had established a preceptory in the hamlet from the end

of the twelfth century. Was this for the exclusive use of the Templars, excluding local folk? Probably

not - as already noted non-Knights (albeit august personages) such as the de Balliol family

worshipped at Dinsley. Perhaps Preston worshippers only drifted to Minsden when regular services at

Dinsley were interrupted several centuries later.

Minsden manor was owned by Guy de Bovencourt until the King claimed it back in 1204. Then,

Minsden was included in the holdings around Hitchin which rested with the de Balliol family until

1295. Robert de Kendale assumed ownership until was ousted by the King on a point of law – of

which possession was not nine points in this case.

In the fourteenth century, Minsden was conferred upon John de Beverle ‘for services rendered’. Then,

it was passed down to his wife and two daughters. In the early 1400s, the manor was sold to the

Langfords, Robert then his son, Edward, followed by later generations of this family. We will return to

Minsden later.

Introducing the Knights Hospitaller

(the Order of St John and the Knights of Malta)

If anything, the origins of the Hospitallers slightly predated the Templars as their Order was

established in the 1070s.

If the Templars kept the routes to the Holy Land open, then the Hospitallers tended those who who fell

by the wayside. They opened a hospice (as distinct from a hospital) at Jerusalem which ministered to

sick and injured pilgrims – they eased their plight rather than treating them.

They were a quasi-religious Order who took vows, donned distinctive clothing and existed to provide

a positive service for others, together with an emphasis on spirituality.

In 1113, their role was acknowledged by the Pope when he issued a papal decree granting the

Hospitallers protection and privileges. They were supported by gifts from crusaders and from well-

meaning donors in Europe, who had an eye on their own salvation earned by their ‘charitable’ gifts.

Increasingly, the Hospitallers became involved in the Holy Land war effort – prevention of injuries was

as important as curing them. Instead of concentrating on the after-care of the wounded and dying,

they sought to protect travellers from attack in the first place by providing an armed escort.

This stance evolved so that in the third crusade (1189 - 1192) they played a major military role for the

first time. As mentioned earlier, there was rivalry between the Templars and the Hospitallers – the

Templars alleging that the Order was created in their image. When the Christians were repulsed from

the Holy Land in 1291, both sets of Knights were criticised for their rivalry which it was considered

contributed to their defeat - ‘...divided they fell’

The Hospitallers were not included in the witch-hunt against the Templars, however, and when the

latter were dissolved, the majority of Templar estates (except those on the Iberian peninsular) were

given to the Hospitallers. They were required to to find ‘yearly two chaplains to celebrate divine

service in the chapel of the manor’ at Temple Dinsley.

The occupants of Temple Dinsley from 1312

There was an interval between the disbanding of the Templars in 1312 and the granting of Temple

Dinsley to the Hospitallers in 1348. R P Mander asserts that in 1307, Temple Dinsley was given to a

money lender, Geoffrey De La Lee probably in settlement of an outstanding debt. The Victorian

County History states that after 1312, the manor was ‘occupied for some years by the lords of the fee’

and that it was then let by them to William de Langford for an annual rent of twenty-seven marks. He

was still a tenant in 1338.

The basis for this observation was a report dated 1338 by Prior Philip de R Thame to the Grand

Master of the Hospitallers, Elyau de Villanova. It stated, ‘there is a manor of 3 carucates of arable

land at a rent of 100 shillings per annum, 60 acres of underwood destroyed by the occupiers of the

Temple. The worth of the aforesaid manor with all outgoings beyond maintenance for the services of

a chaplain for the chapel – twenty-seven marks.’ This was ‘remitted to William, the farmer of

Langeford, who says that the manor was occupied of the Lord’s fee and he who seized it had

occupied it for many years after being annulled by the Templars. The rent – twenty-seven marks.’

During this period the Hospitallers became owners of property by virtue of a statute of 1324. As they

now had access to the fund-raising activities which were one of the main reasons that the Templars

had so much land, in effect the two Orders were merged, despite the fact that the Knights Templar

had fallen from grace. The Hospitallers continued to fight Muslims in the Middle East and the line of

battle-fronts ebbed and flowed - but the cost of warfare escalated as innovations were introduced -

plate armour being more expensive than chain mail, for example.

From the viewpoint of the folk at Preston, probably little changed when the Hospitallers became their

lords and masters, apart from the personnel at the mansion. Indeed, the Hospitallers inherited the

debts and obligations of their predecessors. However, as we will see, although owning Temple

Dinsley, the Hospitallers let the estate to a succession of tenants and the holding of religious services

became less important.

There is one curious historical note that features the Lord of the Manor of Hitchin from 1348, Edward

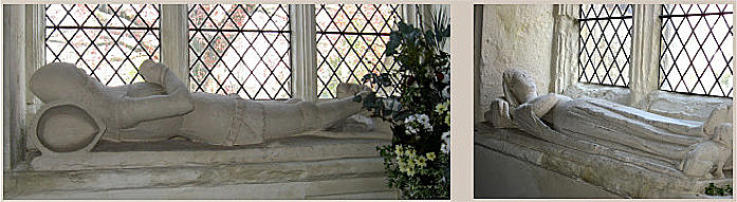

de Kendale and his wife, Elizabeth. The effigy of Bernard de Balliol in St Mary’s, Hitchin has already

been featured, but there are also two other effigies there - of Edward (below left) and Elizabeth.

I have found one comment that both effigies were ‘said to be brought from Temple Dinsley’. If true,

this is an indication of the continuing prominent part Dinsley played in the history of the region.

The Manor of Maidencroft is created from part of the Manor of Dinsley

There is a connection between Edward and Elizabeth de Kendale and the manor of Maidencroft.

Maidencroft manor did not exist at the time of Domesday, as it was then part of the manor of Dinsley.

However, by the middle of the fourteenth century there had been a partition of Dinsley and the new

manor of Maidencroft (which was also known as Dinsley Furnival) had been established. Thus, in

1347, it was recorded that when Margaret de Kendale died, she owned ‘a tenement (or house) called

Madecroft in the manor of Dynsle Furnival’. Edward de Kendale then became the new Lord of

Maidencroft manor.

It follows from this that the size of manors was not set in stone. Indeed, when the Hitchin manor of

Welei ceased to exist, its land was incorporated within its neighbouring manors which included

Temple Dinsley.

Maidencroft manor lay within the parish of Ippollitts, although Salmon noted that it also extended into

the parish of Hitchin. In 1427 it was assessed at 287 acres of arable land and 193 acres of pasture. It

included fourteen houses, five cottages and a dove house. It encompassed land to the north and east

of Preston.

Preston and the plague of 1349

Preston, indeed the whole of Hertfordshire, felt the virulent grip of the Black Death. It was so severe

in Hitchin that everyone died in one district and ‘a street became known thereafter as ‘Dead Street’.

The BBC documentary, Christina - a Medieval Woman, described the remorseless march of the

contagion across Hertfordshire. It travelled at a rate of a kilometre a day and struck Codicote, which

is almost five miles south-east of Preston, on St Dunstan’s Day, 19 May 1349. It embraced Preston a

few days later. Graffiti on a stone pillar of Codicote Church describes the pandemic as ‘pitiable,

ferocious and violent. Only the dregs of the people are left to bear witness’.

As an example of the local impact of the plague, Hine, when writing about Stagenhoe (which is a little

more than a mile from Preston) said ‘the tenants dwindled to a mere handful and the Lord’s demesne

was left derelict and untilled. The villeins and serfs forsook their manors and with fear of death in their

eyes wandered over the country living in woods and hillsides like wild beasts’.

Sixty villages disappeared from the map of Hertfordshire as a result of the Black Death. Included

among them was probably the village and Manor of Welei.

Preston has its own reminder of this virulent pandemic - Dead Woman’s Lane. Local legend has it

that it was named after the plague victims that were buried at nearby Wayley Close.

Temple Dinsley from the middle of the fourteenth century

During the reign of Richard II (1367 - 1400), Hospitallers continued to reside at Temple Dinsley

because the preceptory is mentioned during this period. However, the holding of religious service

here appears to have become spasmodic and had probably lapsed by 1498. At this time, the manor

was leased for the duration of his life-time to John Tong, a preceptor, who undertook to find a chaplain

to perform religious services. Two years later Prior Robert Kendal and the Chapter granted a

chaplain, Robert Shawe, his board at Dinsley at the table of gentlemen. He was paid five marks to

perform services in the chapel.

But, just seven years later, in 1507, the manor was let to Thomas Hobson and then later to Reginald

and Dorothy Adyson, who were also asked to provide the chaplain – the implication being that Shaw

was no longer performing this duty. An inventory of the contents of the chapel was taken in 1514.

Among the items listed were: a high altar, and two smaller alters; images of the Virgin Mary and John

the Baptist; three mass books – one being new; two, old; various vestments; eight alter cloths; a

copper cross and a pair of censors. It seems that even if the will to worship was not constant, the

accoutrements were available. Another tenant was John Docwa. He asked to be buried at either

Temple Dinsley or St Mary’s, Hitchin.

In 1525 there was a bizarre incident which indicates that Temple Dinsley was moving from its

monastic life to a regime of hunting which continued into the nineteenth century. ‘Henry VIII visited

Hitchin and stayed several days hawking and then went to Temple Dinsley. While following his hawk,

he leapt over a ditch with a pole, the pole broke, so that if the footman, Edmond Moody, had not

leaped into the water and lifted up his head, which was fast in the clay, he would have been drowned.’

The involvement of the Hospitallers at Temple Dinsley ended in 1540 during the dissolution of the

monasteries by Henry VIII. They had owned the manor at Preston for almost two centuries. Because

of the lapses in providing divine services at Dinsley, apart from the change of ownership, there was

probably little difference to the daily routine at Dinsley.

The Sadleir family - owners of Temple Dinsley

Henry VIII evidently was uncaring of the religious privileges of his subjects at Preston – he sold them

to a principal Secretary of State and Privy Councillor, Sir Ralph Sadleir (1507 - 1587), together with

Temple Chelsin, for £843 2s 6d - one twentieth of a knight’s fee. He paid an annual rent of £4 9s 4d.

Sadleir was employed in dissolving religious houses such as Temple Dinsley and was wealthy. He

was a diplomat who was frequently employed at the Court in Scotland. He was entrusted with Mary

Queen of Scots while she was a prisoner at Tutbury Castle but was rebuked by Queen Elizabeth I for

taking Mary hunting beyond the environs of the Castle.

As Sir Ralph had been granted the Manor of Standon, Herts by Henry VIII, he lived there rather than

at Preston. However, his son, Edward Sadleir lived at Temple Dinsley. Following Ralph’s death,

Temple Dinsley then passed via five members of the Sadleir family over the next 170 years: Sir

Ralph; Anne (Sir Ralph’s daughter-in-law); Thomas (grandson of Anne); Sir Edwin (son of Thomas)

and Sir Edwin jnr.

Thomas Sadleir (a baptist) was at Dinsley during the time of the English Civil War (1642 - 1651). At

this time, many in the country were deeply dissatisfied with their monarch, Charles I and supported

the Parliamentarians organised by Oliver Cromwell. After Charles was executed in 1649, England

was ruled by a republic until 1660 when control was wrested back by Charles II.

During this period of turbulence, Hitchin (despite its having been a royal manor) and its

neighbourhood were solidly behind the Parliamentarians - it was a Parliamentary stronghold. Thomas

Sadleir was an ardent supporter, not least because Sir Ralph Sadleir had been received into the

family of Thomas Cromwell. However, one of his younger sons at Temple Dinsley on the outbreak of

war, fled from his father and joined up with Royalist, Prince Rupert.

Hertfordshire saw more of the organisation of the Parliament’s armies than any other county in the

Eastern Association (formed by five counties including Hertfordshire) which was created to raise an

army and prevent war from encroaching on their districts. Thomas Sadleir as the grandson of a

famous military engineer, Sir Richard Lee, was part of the Council of War for Hertfordshire and

served on the Committee of the Eastern Association.

Although battles swirled around the Hertfordshire borders, the county saw only a few skirmishes.

When the Royalist army led by Rupert threatened Hitchin in 1643, a force of three to four thousand

Trained-Band Volunteers were mobilised which, in view of Sadleir’s involvement, may well have

included men from Preston. Several of this force were killed in the fields around Hitchin.

During the winter of 1643-4, the army was billeted at Hitchin, much to the town’s people’s annoyance

and Sadlier was in the party dispatched to Parliament to lobby that their soldiers be removed and that

the taxation for their upkeep levied upon Hertfordshire, be abandoned. Thomas himself, despite his

mansion and 600 acres of land, was no longer able to maintain his son because of these dues.

Cromwell raised another army of 3,000 men from Hitchin, Cambridge and surrounding villages. His

recruits came in with ‘incredible speed and alacrity’ and fought during the Roundhead’s victorious

battle of Nazeby. Afterwards, the attention of the Parliamentarians was drawn to Ireland where

Sadleir served as Adjutant-General with some of his Hitchin soldiers. He stormed Ballydoyne,

Graney, Dunhill and Clonmell and was made Governor of Galway.

Present-day Preston may retain a memorial of these days. Hine wrote of ‘the village green at

Preston, then known as Cromwell’s Green’ in 1691. I do not know the source of this information, but

suggest that Hine may have meant what is known today as Crunnells Green - an area in the village

adjacent to the grounds of Temple Dinsley. It was known as Cranwells Green in 1713.

Meanwhile, at Temple Dinsley after 1540, without the patronage of the nuns of Elstree, the chapel at

Preston soon fell into decay and ruin. By 1714, it was replaced by another mansion and was finally

demolished in the late 1790’s. Link: The changing face of Temple Dinsley

In the first few years of the eighteenth century, Sir Edwin Sadleir was forced to sell Temple Dinsley to

offset his debts.

Link: During this period, the independent religious spirit of Preston villagers was demonstrated by

events at Minsden Chapel. These are documented in detail at Minsden Chapel

Views of Temple Dinsley circa 1700

The houses of Preston seem to be shown to the left and outside of the mansion’s grounds. On the

right are a collection of buildings which probably include stables. It is likely that a mill is also shown

here in the right foreground - the building has a medieval hood-mould which may date from the

thirteenth century.

From 1700 to 1900, the history of Preston is more detailed and is described in stand-alone

articles. They are linked below:

The changing face of Temple Dinsley (1700 - 1907)

Benedict and Martha Ithell of Temple Dinsley (1713 - 1767)

Thomas Harwood of Temple Dinsley (to 1787)

Robert Hinde of Preston Castle (1750c - 1786)

The Darton’s of Temple Dinsley - Part One (1787 - 1852) and Part Two (1852 - 1885)

Preston’s schools (1818 - )

Thomas Halsey, tenant of Temple Dinsley (1840 - 1844)

Preston’s Chapel (1850 - 1899)

John Weeks, tenant of Temple Dinsley (1869 -1879)

The sinking of Preston’s well at The Green (1872)

Bunyan’s Chapel (1877 - 1987)

The Pryor family of Temple Dinsley (1874 - 1901)

For the articles describing the history of Preston from 1900, please refer to the Site Map.

History of Hitchin (two volumes) - Reginald Hine

The Early History of Temple Dinsley - Reginald Hine

Hitchin Worthies - Reginald Hine

Highways and Byways in Hertfordshire - Herbert W Tompkins (1913)

The Royal Manor of Hitchin - Wentworth Huyshe

Victorian County History - Hertfordshire

History of Hertfordshire - Robert Clutterbuck (1815 - 1827)

Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire - Sir H Chauncey (1700)

The History of Hertfordshire M N Salmon (1728)

The Knights Templar - Helen Nicholson

The Knights Templar - Dr Evelyn Lord

The Manor House of Temple Dinsley - R P Mander

The Origins of Hertfordshire - Prof. T Williamson (2000)

The Writings of Nina Freebody, Back Lane, Preston (Link: N Freebody)

The Place Names of Hertfordshire - J E B Glover (1936)

The Penguin Translation of the Domesday Book - Prof G H Martin (2002)

Handbook to Hitchin and the Neighbourhood - C Bishop

History of Hertfordshire - J E Cussans

Stagenhoe and the Spanish Countess who Dipped into Spiritualism - R J Pilgram

The History of Stagenhoe - Reginald Hine (1936)

Hitchin and its Neighbourhood

Bibliography