The Knights Templar arrive at Preston

A detailed history of Preston: Part two

Many, influenced by movies and novels such Daniel Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and Angels and

Demons, associate the Knights Templar with treasure, mysterious symbols that point to its location

and a frenetic race with opposing ruthless secret societies to discover it - with disfigured corpses

strewn along the way.

As a result of this frenzy of interest, students of the Knights Templar subdivide the many books about

them into two categories: ‘Orthodox’ (above left) and ‘Speculative’ (above right). This ‘history’

concentrates on the orthodox view of the Knights, but, tantalizingly, a little speculation may creep in

later.

In the eleventh century AD, many devout Christians from Western Europe undertook the long

pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Among the revered, holy sites at the city were the Garden of Gethsemine,

Mount Calvary and the tomb of Christ. Pilgrims made their journey to sight-see, worship and

ultimately to have their sins forgiven

However, what was already a gruelling trek became increasingly dangerous and impossible.

Jerusalem was in the grip of non-Christian Turkish overlords who blocked the approach of

worshippers to the sacred shrines. Pilgrims were attacked – many were slaughtered; others were

sold into slavery.

Responding to this religious hostility, in 1095, the Pope launched a popular and powerful campaign to

free the Holy Land from the infidels by using soldiers of Christ. The Crusaders were born. These

rampaging knights were later distinguished by the scarlet cross emblazoned on their coats. After four

years of bloodshed the Turks had been ousted and Jerusalem was in Christian hands. The first

Crusade of 1099 had been a satisfying success for Christians.

With the promise of a safer journey, worshippers again streamed towards the Holy City - but other

perils lay in their path: ambushing robbers, marauding Muslim Saracens and voracious wild animals.

Matters came to a head in the Easter of 1119 when 300 pilgrims were massacred by Saracens near

Jerusalem. As a reaction to this butchery, nine knights (most, if not all, were French) pledged to

protect Christian travellers. The recently-installed King of Jerusalem provided a home for the knights

in the Temple – these intrepid few became known as the Knights Templar.

.

The Knights Templar - Monkish Knights or Fighting Monks?

This subject is relevant as it may explain why the Templars decided to establish a preceptory at

Preston.

We return to the field of conflict at Jerusalem - the Templars needed reinforcements and money to

wage their war. In 1127, the first Templar Grand Master, Hugh de Payens, after visiting Normandy,

crossed the Channel to England and was ‘welcomed by all good men. He was given treasures by

all...’. He called for people to go to Jerusalem. His recruitment drive was a success. This was the first

mention of the Knights Templar in Britain.

The Templars were also brothers in a religious Order who led a monastic life. ‘They dedicated

themselves to God, taking vows of chastity, poverty and obedience’. In fact, the foremost aim of the

Knights is debatable – were they warrior monks or monkish warriors? Where should the emphasis to

be placed?

These descriptions may appear paradoxical as monks eschew the spilling of blood. But the Templars

viewed fighting infidels as an act of devotion. War was a version of prayer. Their battle was just and

righteous as it defended the Holy Church. So, ‘onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war’!

Their attire was symbolic - they were commanded to wear white mantles and cloaks to show that they

had emerged from darkness into the light of purity. The red crosses on their mantles were added later

to distinguish them from other fighters. The knights kept their hair short - but they did not shave their

beards.

To understand the impact on Preston of the Templars, one should discern their religious aspect

because (as we will see) this explains both how they acquired their land in the hamlet and also their

manner of life there.

The Knights Templar and Preston

How did Temple Dinsley become established?

As the Templars were a significant religious body, they were bestowed grants of land in return for their

awarding redemption of sins and absolution to the donors. These awards eased the recipients

conscience and gave them confidence of being accepted in heaven after their demise. Thus, spiritual

well-being and deliverance was effectively purchased by the gift of land. The gift of Temple Dinsley

was a spiritual back-hander.

There is documentary evidence which indicates that the Templars had a foothold at Dinsley before

1142, and then during the seven years between 1142 and 1148, there was a flurry of five separate

grants of rights and land to the Templars at Dinsley: (These were described in Part One of this

history.)

Why Dinsley at Preston suited the Knights Templar

Given that Dinsley was a grant, the most likely reason for the Templars establishing a base there was

the site’s seclusion. Preston is perched on an elevated ridge of the Chilterns. Even today, there are

swathes of woodland in the area at Wain Wood and Hitch Wood. Nine hundred years ago, the forests

in the district were even more extensive. Today, the site nestles in a natural hollow (see modern-day

photograph below) – it ‘stands at the head of a long ravine that slopes gently toward the east in the

direction of Minsden Chapel’.

As a result, Dinsley was isolated – a most suitable location for a withdrawn monastic order and it

might be bourne in mind that Preston had religious roots as noted earlier. Despite its isolation,

Preston was a mere thirty miles from London and reasonably close to the major ancient highways of

the Great North Road and the Ichnield Way.

The birth of Temple Dinsley

Soon after acquiring the land (and before 1200, as a chapter or meeting was held there sometime

between 1200 and 1205), there was a preceptory at Preston - this was a cross between a monastery

and a chapel. Whether this was adapted from the original ‘priest’s tun’ at Preston or built by the

Templars is not known.

Huyshe writes, ‘The chapel would probably (my italics) be among the earliest of the buildings to be

erected for the fraternity’.

Whatever its background, there was now a community and religious house here and so Temple

Dinsley was created. The Victorian County History remarks, ‘Not much is known about the preceptor,

but it was perhaps fairly important’. The first historical reference to ‘Dynesle Temple’ was in 1294.

Its Master or Preceptor was answerable to the Grand Master of Templars. Preceptors at Dinsley

included Richard Fitz-John (c1255), Ralph de Malton (c1301) and Robert Torvile (1308).

Life at Temple Dinsley for the Templars

Although there are no plans of the original structures, if the normal practices of the Templars were

followed, there would have been ‘a large complex of buildings’. This is the picture surviving

documents convey. They included a chapel, hall, smithy, bake-house and a graveyard (after 1543, the

graveyard became the kitchen yard).

The Templars’ preceptories were guarded by strong walls and a gatehouse. Outside were the

demense (or lord’s) estate and their tenants. As well as the brothers, there was a resident bailiff, a

carter, four ploughmen, four labourers, a cook, a gardener and six pensioners. In the time of Bernard

de Balliol, fifty people were listed as holding land and cottages on the estate. They included a

cottager, a forester, a smith, a cloth-comber and a blood-letter.

The brothers lived simply in walled enclosures that had a hall in which they ate and which contained a

table, trestles and a washbasin. They also had chamber or bedroom that was furnished with beds and

clothes bags. Here, the knights slept fully clothed and silent in dormitories with lamps burning. If the

inventories of 1308 are accurate (they may have been listed after the preceptories were plundered)

the Templars lived a frugal life with few possessions or comforts.

The brothers were dedicated to prayer, observed their office day and night, fasted and preserved

silence. When they sat at their table, they observed rank. Theirs was a fairly elderly community as the

younger men were fighting overseas.

The precise location of the chapel at Dinsley is unknown, but its existence is confirmed by three

substantial artefacts. Firstly, at St Mary’s Church in Hitchin is the ‘battered effigy in Purbeck marble of

Bernard de Balliol’ (discovered in 1728) which would originally have occupied pride of place at the

(Dinsley) chapel’ (pictured in Part one). Herbert W Tomkins states that this is in the recess of one of

the windows of the north aisle of the parish church at Hitchin and describes it as ‘a mutilated,

featureless effigy’.

The figure was re-united with the second artefact, a foot (‘part of a sculptured foot bearing chain mail

and spur’) which was found at Dinsley in February 1899.

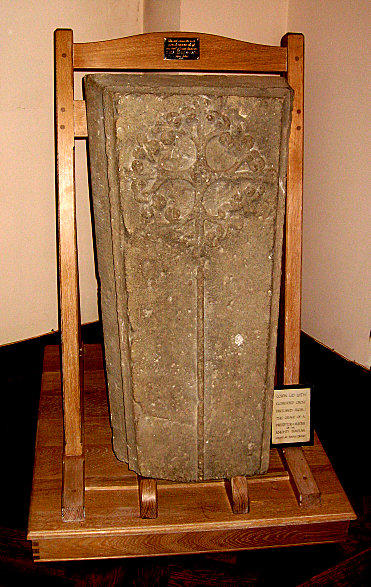

A third artefact from Dinsley is displayed at St Martin’s Church, Preston (below). It is a grave-stone

cover, ‘carved with a floriated cross that once marked the resting place of a Templar Master’.

In 1913, Tomkins added some information about this find: ‘Fortunately for me, a discovery was made

a few days back which has set others thinking once again of the men who held this manor so long

ago.

‘Leaving the village green, I obtained entrance to the private gardens of Temple Dinsley and here

lying upon the ground near the house, in a spot shaded by pines and guarded by an effigy of Father

Time with his scythe and hour glass, is a large stone coffin lid which was found by some workmen

when digging in the grounds. The coffin itself was missing. On that lid is a filial cross upon a rod or

staff with a central disc and foliated extremes’.

Tompkins claimed that this specific pattern was among the insignia of the Knights Templar. This

discovery reminded him of another find nearby, the ‘sculptured foot’, which was mentioned earlier.

Preston was agog: ‘...I find no small interest is evinced by them in those stories which they have

heard from time to time’.

Tompkins sat by this ‘old, old stone’ and listened to all that the gardener had to tell him. ‘...not far from

where I am sitting is the mouth of a subterranean passage. It has been opened, as I am told, from

time to time, but never fully exposed. The story runs that it leads from here to Minsden Chapel and

that, “once upon a time”, a second passage ran from the Priory at Hitchin and met that at Temple

Dinsley almost at right angles’.

Now, a note about the Templars and tunnels: National Geographic filmed a documentary about the

Templars which featured the tunnels they built at Jerusalem - the Templars were tunnellers. There is

also a rumour that beneath Hertford there is a honeycomb of passages dug by the Templars to

facilitate secret movement about the town. R J Pilgram wrote the following about Stagenhoe House

(which is little more than a mile from Temple Dinsley): ‘There has been recurring talk of a secret

passage at Stagenhoe to Temple Dinsley, nearby. Mr Bailey-Hawkins (owner, 1895 - 1922) tried to

investigate it with some of his men, but they were driven back by foul air. When Mr Dewar owned the

place he stated that he was extremely interested to reach the end of the tunnel, which had collapsed

in many places. It seems unlikely that he ever did so. Reginald Hine, author of a history of

Stagenhoe, did not regard the passage as having any significance.

It was moreover a danger and Mr Hawkins car, leaving the forecourt, caused it to collapse.’

However, when describing how Stagenhoe mansion was underpinned by girders in the cellars, Hine

wrote, ‘It was when these girders were being installed that a secret passage was discovered leading

(so it was said) in the direction of the Church. It is a pity that it was then bricked up, for speculation as

to its course, destination and purpose has been rife ever since. For the most part, one is inclined to

be sceptical about such passages...’

Two floor tiles dated mid-thirteenth century found at Temple Dinsley and given to North Herts

Museums by historian Chris Sansom. (Left) The Agnus Dei tile. (Right) The arms of a brother.

Images used by kind permission of NHDC Museums

Further evidence of the original Temple Dinsley has been discovered in the form of a few of the floor

tiles of the chapel, embellished with heraldic designs shown above. Skeletons of some of the monks

have been dug up in the kitchen yard. A skull was used by Lord Hampden, Henry Brand, on his study

table as a reminder of his mortality (a memento mori) when he was tenant of Temple Dinsley. Lodged

with the bones was a pewter chalice of the early fourteenth century. This was discovered on 17

February 1887. When Douglas Vickers owned the estate, a fourteenth-century bronze jug was

unearthed and presented to Hitchin Museum by Mrs Barrington-White.

Away from the main structure, there were farm buildings in the enclosure at Dinsley - which confirms

that the knights led both a religious and an agricultural life. The Templars owned a large holding of

land at Preston next to Dinsley. Only a quarter of the Templars land at Preston (27%) of land at

Preston was held in demense, (that is, set aside for the Templars’ use) and for centuries this was

referred to as ‘Temple Land’. The rest of the manor was tended by their tenants: freemen, villeins

(with holdings from a few acres to 1-2 virgates) and cottars who had a house and a small piece of

land and probably worked for the other two classes.

The Templars received further grants of land: thirteen acres in Kings Walden, some at Charlton

(1244-5 from Maud de Lovetot) and two marks rent in Welles at Offley from John de Balliol.

They also enjoyed fishing rights on the River Hiz and free warren (from Henry III in 1252/53) in their

demesne lands of Dinsley, Stagenhoe, Preston, Charlton, Kings Walden and Hitchin. This enabled

them to kill game in those districts. Even in the twentieth century, the Lord of Temple Dinsley had the

right to stand on the steps of Stagenhoe House on Christmas Day and discharge a shotgun.

The Templars also had the right to erect gallows. They hung a man at Baldock in 1277, which

indicates that their jurisdiction extended to this district. In 1286, they hung Gerle de Clifton and John

de Tickhill for stealing a silver chalice and four silver teaspoons from a Dinsley priest as well as Peter,

son of Adam, for taking and torturing a woman.

Religious services at Temple Dinsley from 1218

The niece of William the Conqueror, Judith, formed the Benedictine abbey of Elstow, Bedfordshire

towards the end of the eleventh century. It was seen as a royal foundation and its property, which

included St Mary’s, Hitchin, was large and scattered. These had the right to appoint a priest of the St

Mary’s.

Link: The Nuns of Elstow

In 1218, the Templars agreed with the nuns of Elstow that they should provide a resident chaplain at

Dinsley who would celebrate matins, mass and vespers on Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays in the

morning, followed by vespers in the afternoon. The nuns thus provided a silver mark each year and

four pounds of wax for the candles in the chapel. The Templars paid for services rendered by the nuns

by giving a tithe from all the land that they ploughed in Hitchin, as well as any land that was ‘newly

broke up and sown’.

However, if we imagine Temple Dinsley as a complex populated by knights in resplendent armour, this

would be a mistake. Reginald Hine has been taken to task for painting a romantic picture of the

preceptory in his Early History of Temple Dinsley. This was triggered by his observation that there is a

meadow close by called Pageant Field. He suggested that ‘we shall do wisely, I think, to follow the

prompting of that word (pageant)’. He then dreamed of standing on Preston Hill and watching a

‘procession of the ages’ looming through ‘the mists of time and standing out in bright armour’.

Along came (spoilsport, but correct) Evelyn Lord in 2002 and dumped a douche of ice-cold water over

this fanciful whimsy – she wrote dismissively, ‘Pageant Field did not get this name until 1729...holding

tournaments would have been against the Order’s Rule as encouraging competition and pride’. Do get

a grip, Reginald!

Rather, Temple Dinsley had the trappings of a trapist-like monastery.

The importance of Temple Dinsley

Temple Dinsley at Preston is recognised as ‘the most important preceptory (of the Templars) in the

British Isles outside London’. The preceptory ‘became the most important in South East England’.

(BBC History)

The administration of the Templars outside London was through provincial chapters. By the end of the

thirteenth century, these important assemblies were held at Temple Dinsley. Chapters (or AGMs in

today’s parlance) were held between 1200 -1205;1219 - 29; 1254 - 59; 1265; 1292; 1301 and 1310.

As a result there was an impressive list of visitors to Preston. These included Henry III and the last

Grand Master, Jacques de Molay. In 1270, the last English Master, William de la More was received

into the order at Preston. Twenty year later, in 1290, the following dignitaries graced Temple Dinsley:

Robert De Torvile (master), Thomas de Bary (chaplain), Robert Daken (preceptor of Scotland),

Thomas de la Fenne ( from Bisham), Robert le Scrop (from Dandford), Robert de Barrington (from

York), Roger de Cranford (from Bruer), Robert de Gloucester (preceptor of Ireland) and Thomas of

Toulouse (preceptor of London).

Treasure and the Templars

The Templars are often linked with hidden treasure. In the twentieth century, a girl from Princess

Helena College (PHC) was found at class-time wading ‘up to her middle in the lower pool in the sure

and certain hope that at any moment her toes might touch the bars of gold and the fabled iron

casket’. Hine reported in the 1920s that men and women in ‘agonies of baffled expectation have been

digging for 600 years the buried treasure’ that still eludes them. Why was this fantasy of buried bullion

believed?

The Templars evolved a system of banking. This was due to practical necessity. It was simply not

feasible to travel any distance, let alone thousands of miles to the Holy Land weighed down with gold

- a tempting target for any bandit. So, the Templars evolved a monetary system which allowed money

to be transferred between their preceptories on paper. As a result, an amount written in France or

England could be drawn upon in the Holy Land - it was effectively a credit note.

It wasn’t only the Templars who needed this facility. Their services were used by kings and noblemen

to collect and store taxes, pay ransoms and act as money couriers. The Templars offered a safe

deposit service and were trustees for the payment of annuities and pensions. Of course, large

amounts of money still had to be carted around, against which paper could be raised and the

impression was given that the Templars were incredibly rich to those witnessing this ancient

Securicor-like business in transit . They missed the point - the hefty bags did not contain the

Templar’s money – the Knights were mere custodians. They were akin to the security guard, earning

the minimum wage, who carries £100,000 into a bank: that is not his money. The revenue that the

Templars earned was sunk into the bottomless pit of financing their army in the Middle East.

It was this misconception of their part in the banking world that created the fiction of their wealth and

hidden treasure. The reality was that they were poor (that is, financially poor) monks. When the

Templars were attacked in the early fourteenth century, little of worth was found, not because it had

been spirited away, but because it had never been.

Even the King of England was not immune from accepting as fact enticing rumours about treasure

troves. After Dinsley was wrenched from the Templars in 1309, a commission was issued to ‘inquire

touching goods of the Templars in the county of Herts’. Nothing was found.

In the fourteenth century, believing that possibly Temple Dinsley had a complex of underground

passages and buried treasure, Edward III sent a team to Preston to dig for the buried fortune – the

foragers were to have a half share of the spoil. Another blank.

Wentworth Huyshe in The Royal Manor of Hitchin described an conversation with Mrs Anstruther who

lived with her husband (most appropriately, a Lord of the Treasury) at The Cottage on the Hitchin

Road at Preston, which was part of the Temple Dinsley estate:

‘Rumour murmurs a half-forgotten tale how somewhere in that garden, perhaps beneath

the straight grass walks, perhaps beneath the sunflowers and the pansies, the clumps of

daisies and of dahlias – somewhere in that garden – lies a wealth of hidden treasure;

jewels, rich and rare, rubies and diamonds, emeralds and sapphires and gold and silver

galore hidden centuries ago by desperate men whom the King was despoiling of their

own..But the exact spot where that treasure lies, no man wots of today, though some of

the old folk in the village babble still of a certain oak tree, so many feet to the eastward

of a certain pool; yet despite their babbling it is a fact that whereas men in the course of

their daily labour have dug and trenched every inch of that garden, nothing have they

brought to the surface, except some human skulls and bones which seem as though the

bones of men. But never yet the treasure.’

Why the Knights Templar fell from favour

In 1291, despite all their support and battling, the Christian armies were repulsed from the Holy Land.

This created a fundamental crisis for the Templars: their essential raison d’etre was non plus pas.

Furthermore, the recruitment stream was drying up and theirs was an ageing force. Their rock (petra)

in this time of need was, appropriately, the Pope.

The military problem in the Holy Land was exacerbated because the Christians had splintered into

separate armies – each rivals, yet with the same aims. Among the contenders of the Templars were

the Knights Hospitallers, who were to feature later at Preston. The Grand Masters of the Templars

and the Hospitallers met the Pope in 1306. The two main bullet-points on the agenda were how to

merge the two orders and the launching of a new crusade.

However, there was another more influential power struggle brewing. The Pope’s authority was being

challenged by Europe’s kings, notably Philip IV of France. As many of the Templars lived in France,

they were squeezed between their king and their increasingly weakened protector, the Pope. Added

to the cauldron were the jealous glances Philip directed toward the Templars’ supposed wealth and

his perception that they were religiously corrupt and evil and that he was Mr Right.

Matters came to a head at dawn on 13 October 1307. Philip ordered the arrest of all the Templars in

France. They were accused of terrible crimes: of sodomy, heresy and apostasy. Permitted to torture

his victims in France, under extreme duress some ‘confessed’ that the charges were true. This gave

Philip still greater power to spread his attack abroad. The ‘Rock’ crumbled. The Pope issued a Bull or

edict against the Templars.

This spiritual tsusami created a wave of attack even in the heights of secluded Preston. Despite his

reservations, the King of England, Edward II, had no choice but to also arrest the English Templars

because of the papal Bull - to ignore it was to put the well-being of his very soul at risk.

Thus, on either 9 or 10 January 1307, the rural calm of Preston was shattered by the arrival of the

Sheriff of Hertfordshire’s men at Temple Dinsley. They seized six Templars and dragged them away to

face trial. (Perhaps Reginald Hine would have been on surer ground if he had pictured this wintry raid

while standing on Preston Hill.) Two of the brothers were taken to the Tower of London and the other

four were escorted to Hertford Castle. The known Templars arrested at Dinsley, included Henry Paul,

Richard Peitvyn who had been at Dinsley for forty-two years), Henry de Wicklow and Robert de la

Wold.

At the time, there were six other men living as pensioners at Dinsley, together with two priests,(who

acted as chaplains) and three boarders. Little wealth was recovered during the raids on Templar

property in England.

The inquisition of the English Templars was held in the Tower of London. By English law, torture was

not an option for the interrogators, however they were chained in solitary confinement. Temple

Dinsley came under the spotlight when Stephen of Stapelbridge gave evidence that, when he was

received at Dinsley and pressured by a ring of Knights with drawn swords, he had been told to spit on

the cross and deny God. He claimed that this was a common practice at Dinsley. Stephen’s testimony

was corroborated by Thomas de Tocci who added that the Master at Dinsley, Brian de Jay, had

denied that Jesus was the Son of God many times.

Although the charges described against them were trumped up and not clearly proved, the result of

this probably unjust persecution of the Templars was that they were found guilty and disbanded by the

Pope on 22 March 1312.

What was the effect of this on Temple Dinsley? The Templars had been given property to help them

defend the Holy Land. They were discredited and the raison d’etre for their holding land no longer

existed. The Pope decided to give the majority of the Templars property, including Dinsley, to their

rivals, Knights Hospitallers.

Link: Part three