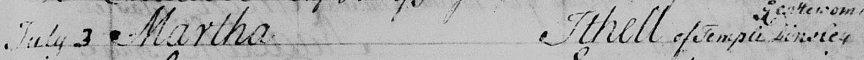

Benedict and Martha Ithell of Temple Dinsley

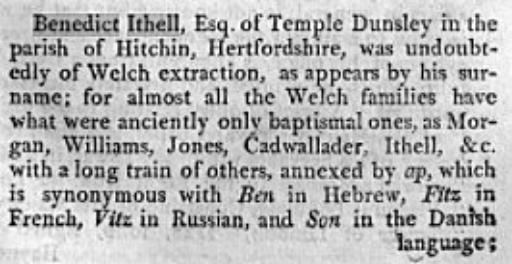

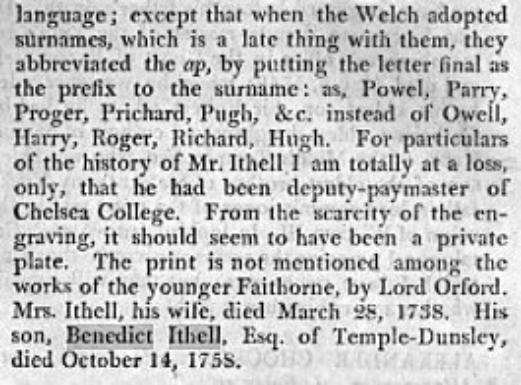

In 1806, Rev. Mark Noble suggested that Benedict Ithell was of Welsh extraction (his estate included

holdings in Herefordshire) - Biographical History of England. (See below - the engraving referred to

therein appears to be the image of Ithell shown above):

The Ithell coat of arms

There was a further comment about Ithell’s family by Ralph Churton, Dean of St Pauls, in 1809,

“…kinsman perhaps (to Dr Ithell Master of Jesus College) as the name is not uncommon to Benedict

Ithell Esq. of Temple Dinsley who is mentioned as having a curious portrait of Dean Colet, founder of

St Pauls School”.

In view of what happened to Ithell’s estate after his death, it is perhaps as well that these comments

were perhaps not in the public domain at the time.

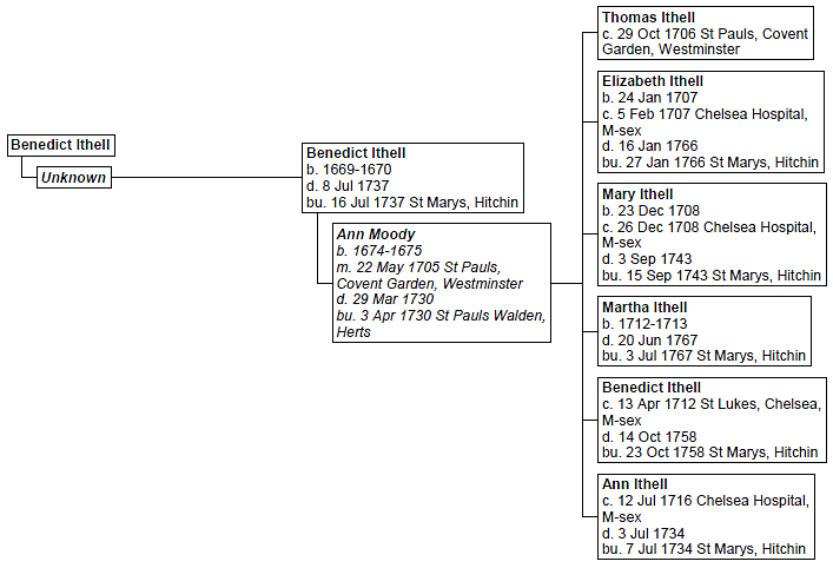

It is of interest that Benedict and Ann had two sons - Thomas, born in 1706, is not usually mentioned

but he is recorded in the International Genealogical Index (IGI). I cannot find a note of his burial. Also,

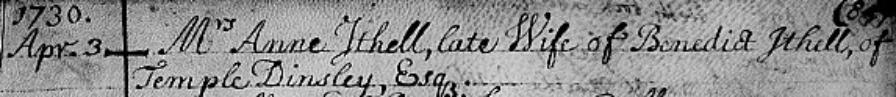

that Ann, Benedict’s wife, was buried at St Pauls Walden, Herts, in 1830 - the rest of her family were

laid to rest at St Mary’s, Hitchin.

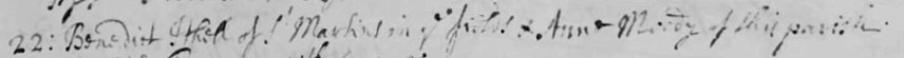

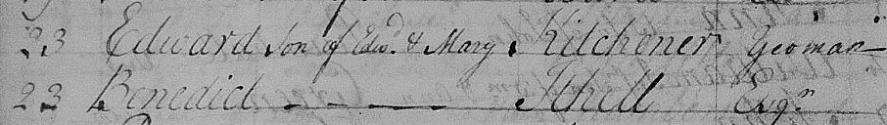

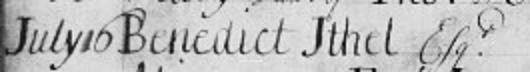

What follows are the records of Benedict and Ann’s marriage and Ithell burial records to support the

tree shown above. (Note that Benedict senior was living at St Martin in the Fields, Middlesex, when he

married and Benedict jnr was buried on the same day as Edward Kitchiner, the son of Edward and

Mary.)

Benedict Ithell jnr was Deputy Treasurer of Chelsea Hospital. His estate included holdings in

Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Bedforshire.

In August 1712, Benedict bought Temple Dinsley for £3,922. Possibly he purchased the estate for the

hunting potential of the land surrounding the building rather than for the house itself. The Sadleirs had

evidently not been able to maintain the house in a good state of repair because two years later, in 1714,

Ithell built a new mansion close to the old Temple Dinsley (evidently, the old house was left standing

until the 1790s). The house had a heraldic badge in the form of a rising bird and the inscription ‘1714’ on

rainwater heads. The new mansion was just to the south of the old building.

Ithell also restored estate cottages in Preston. He was appointed as Sheriff of Hertfordshire in 1727 and

was made a trustee of Hitchin Grammar School. He formed a bond with Ralph Radcliffe of Hitchin

Priory. The pair drove to St Mary’s Church at Hitchin on Sundays in a style guaranteed to upset the

church wardens. Their gilded coaches were ‘emblazoned with arms and their crests glittering in silver

radiance from every part of the harness where a crest could possibly be placed’. They swung through

the south gates and along the gravelled path of the graveyard to the entrance of the porch to the

accompaniment of the tolling church bells. The pageant was ‘brought up in style with straining and

struggling of horses, cracking of whip, glistening of harness and flashing of wheels through gravel,

horses fretted into a foam, dashing the pebbles against the poor pedestrian people’.

This ‘flaunting parade of petty lordings’ so incensed a churchwarden, Richard Whitherby, that without

consulting the vicar or his fellow churchwardens, on Saturday night (9 November 1734) he drove a

great beam into the centre of the gravelled way and girdled three chains and padlocks around the

entrance gates. That would fix their little games!

He reckoned without the resourcefulness of Radcliffe. He sent his carpenter to break the chains and

saw down the offending beam - all this just in time for Ithell to drive through in triumph. Whitherby still

had some cards to play. On the Monday morning, he summonsed both the carpenter, for malicious

damage, and Ithell’s coachman, for trespass. They escaped on the grounds that no apparent

annoyance had been visited on the corpses in the graveyard! While this makes for a good story, if this

was typical of the man, one wonders how such a squire behaved towards the ‘poor people’ of Preston.

Carriages and Benedict also featured in another historical tit-bit: he ordered the manufacture of a

carriage from London. The makers requested a measurement of local ruts so that his carriage should

run smoothly.

Benedict Ithell snr died on 8 July 1737, aged 67. He was interred within St Mary’s Church immediately

below a magnificent monument (shown below, left). This recorded details of the burials of himself and

his wife and children who had also been interred at Hitchin. Benedict snr’s will was proved on

14 September 1737. He asked to be buried ‘in the vault lately made by me in the Parish Church of

Hitchin’. He bequeathed to each of his daughters, Elizabeth, Mary and Martha, a legacy of £2,000. His

estate was left to his son, Benedict jnr and thence, if he died without issue, to his daughters. They later

died without marrying and were all buried at St Mary’s.

There was another significant clause to Benedicts will. He gave his son ‘liberty to commit waste’ except

in the homes and buildings in Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire - ‘waste’ being the harmful or destructive

use of property. And this arrangement was to be supported by ‘my cousin’, Samuel Clark and William

Ridge, a haberdasher. Here was significant confirmation (in the light of what was to happen when his

daughter, Martha’s, will was executed) of Benedict’s relationship to Samuel Clark, as we will see, and

may well have ensured that the old building of Temple Dinsley remained standing for several decades.

Benedict’s will also specifically mentioned the ‘dwelling house and gardens at Temple Dinsley’.

His son, Benedict jnr was buried at St Mary’s and a reader about his qualities which was composed by

his sisters, Elizabeth and Martha, is on a wall (see below, right).

Martha Ithell (1712c - 1767)

Martha’s older spinster sisters died in 1734, 1743 and 1766 and were all buried at St Mary’s, Hitchin.

It would therefore be reasonable to conclude that they lived at Temple Dinsley, a view confirmed by

the burial records of two which stated that the mansion was their residence at the time of death and

that it had been their mother’s home when she died in 1730. The Herts Militia List indicates that

Thomas Harwood was employed as a servant there from around 1758. After Elizabeth Ithell died in

1766, Martha was the surviving Ithell who therefore inherited her father’s estate.

Martha’s will was contested by a cousin, Benedict Clarke, a butcher from St Georges, Southwark,

London, who was seemingly unaware of the terms of Benedict Ithell’s will, knowledge of which would

have saved him from going to some lengths to attempt to establish his family relationship to Benedict

Ithell.

It has been written that Clarke challenged Martha’s soundness of mind, but from the bundle of

documents at Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies (HALS) which relate to the case, Clarke

actually claimed that as Martha had died without issue, he, as her cousin, was her true heir. There

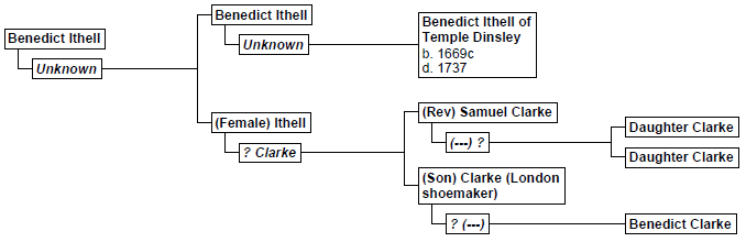

are some pages of scribbled and partial family trees, without dates or names which, if set out, would

look like this:

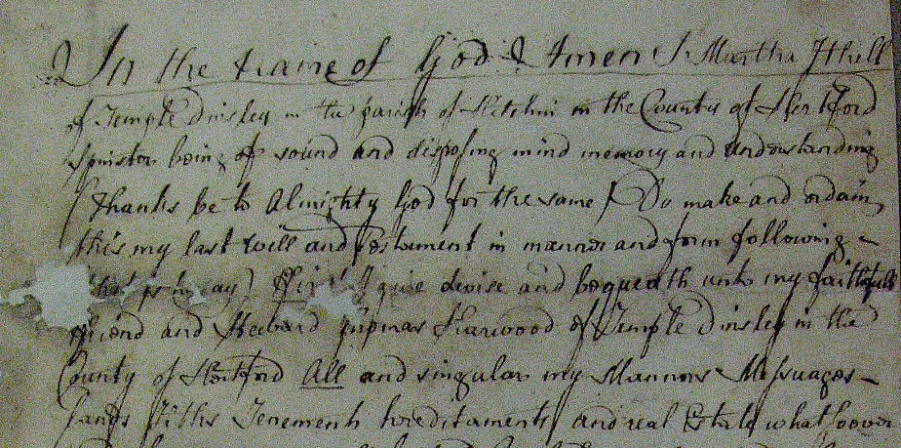

Martha Ithell’s will

Below is a section of Martha’s original will, dated 3 April 1787 and witnessed by Edward Kitchiner

(sic), James Whitney and James Ware. It clearly states that she left everything to her ‘faithful friend

and steward Thomas Harwood’ who was also to be her sole executor: Link: Harwood

The key person here is Rev Samuel Clarke who had died at East Dereham, Norfolk ‘7 or 8 years’

(before 1767) ago’ (there is a mural monument to him in the parish church) and who had been the

minister of Little Brick Kiln (sic - Little Brick Kiln is probably Little Brickhill, Bucks.), about forty years

ago (ie circa 1727). Samuel had an older brother who lived in London, whose son was Benedict

Clarke. It was said that Samuel called an older Ithell, his ‘second or third cousin’. (By a sweet

coincidence, a Thomas Harwood was installed as a curate at Little Brickhill in 1672!) There was no

dispute about this, particularly in view of the wording of Benedict Ithell’s will, which mentioned his

cousin, Samuel Clarke. However, Martha’s will was properly drawn up and witnessed by men who

knew her. Thomas’ claim to the Ithell estate was water-tight.

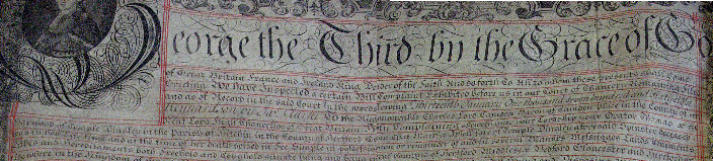

As a means of refuting any further disputes about his inheritance, Harwood arranged for Hitchin’s

Richard Tristram to interview the witnesses to Martha’s signature and draw up an affidavit which was

incorporated into an “Exemplification” of his rights as Martha’s legitimate heir, issued by the Court of

Chancery (partly reproduced below):

Tristram’s itemised bill is included in the bundle at HALS. It was £6 2s 2d well spent by Thomas!

This is an epitome of what was written in the Exemplification:

The three witnesses to Martha’s will were interviewed at The Sun Inn, Hitchin. They

confirmed that they had witnessed her signing the will in a room in the mansion of

Temple Dinsley.

They were: Edward Kitchiner of Offley Holes (aged about 40), yeoman, who had known

Harwood ‘many years’; James Witney, a butcher of Gosmore, Ippollitts, who added that

Martha had “expressed great satisfaction in having settled her affairs” and James Ware,

a gardener at Temple Dinsley (aged about 25) who had known Harwood for three years

and Martha for a year and a half. Ware said that he had seen Martha make her will on

3 April 1767 on one sheet of paper marked with a letter and that the signature was in her

handwriting.

Other witnesses were also interviewed. James Garth, a gentleman aged about fifty

years, who had known Harwood for fifteen years and Martha for ‘many years’ testified

that she had owned property at Great and Little Wymondley and that there was an entry

in the Manor Court book that she had ‘surrendered this property to the use of her will’. A

verified copy of this was shown. Tristam Lawrence Times, a gentleman of Hitchin aged

about 28 years (who had known Harwood for five years and Martha for four years)

testified to a similar entry in the Kings Walden Manor Court Book with respect to her

holdings there. This action confirmed that Martha intended her will to be invoked.

None of these five had known Benedict Clarke.

He claimed to be Martha’s ‘cousin and heir in law’ but the Court expressed their view

that there were ‘many uncertainties and imperfections’ in Clarke’s case; that he was not

‘able to sufficiently answer the will’ and that his claim was ‘uncertain, untrue and

insufficient in law’.

One further point of interest is that the full extent of Martha’s estate became a little clearer from these

proceedings as it noted that she had holdings in the counties of Hertfordshire, Middlesex,

Bedfordshire, Gloucestershire and Herefordshire.