Wells and wind-pumps

In modern-day Britain, perhaps we take for granted that when we want water, we simply turn

a tap. Another article on this website (Link: Ponds) has highlighted how ponds served as the

lifeblood of a community, sustaining man and beast for centuries.

This page is devoted to the wells and wind pumps of Preston in the late nineteenth and first

half of the twentieth centuries.

The well at Preston Green, photographed above in the 1950s, is an historic, iconic image of village

life. Its picture appears on the header of today’s Preston Parish News letter and it is featured on the

title page of the Preston Scrapbook (1953). Yet the background to its sinking may be misunderstood.

The Scrapbook states: ‘The Well on the Green was the gift of William Henry Darton........It was dug up

in the hot dry summer of 1872 when most of the ponds had dried up.’ This may well be true, but

documents that have recently come to light paint a different picture. The first is a letter written by

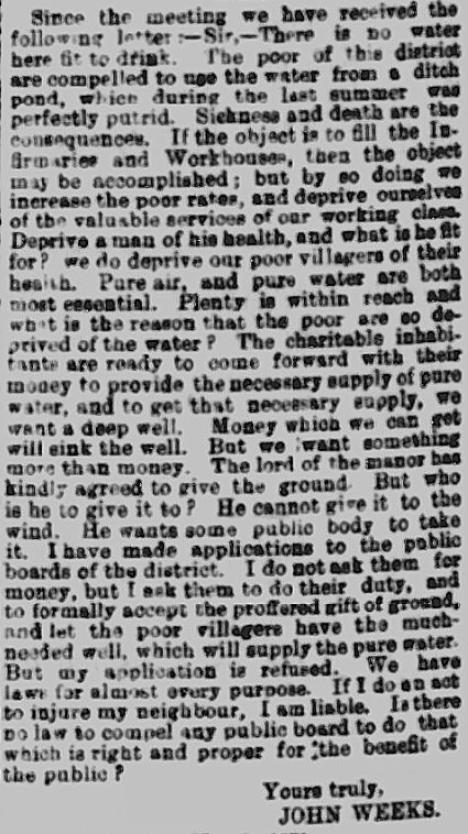

John Weeks, the resident of Temple Dinsley, to the Hertfordshire Express dated 20 September 1870:

This was followed by a letter written on 12 October 1870 by Weeks to William Henry Darton which

was couched in similar terms:

‘I have observed with deep regret that my poorer neighbours in the village of Preston

have no water fit to drink and medical gentlemen of the district have certified to me

that a large amount of illness results from the unwholesome and filthy water which

the cottagers are compelled to use.

I, with many other residents in the neighbourhood, consider it a duty we owe to those

who cannot assist themselves to use our utmost endeavours to procure such a

supply of pure water as is necessary to preserve the life and health of the inhabitants.

I therefore beg to solicit your co-operation in this desirable undertaking by giving

permission for the opening of ground on Preston Green on which to sink a deep well

and also granting a convenient place where the excavated soil may be deposited.

I shall be glad to receive any donation you may be pleased to give in furtherance of

the work which although urgently and undeniably needed, cannot be undertaken

without your sanction and consent.’

There was a further exchange of views between Weeks and the Hitchin Board of Guardians in

November 1870:

The newspaper added an editorial comment to the debate: ‘Probably the Board of Guardians are not

bound to accept the offer in the form proposed, but we believe that if the well was sunk the guardians,

as the Local Authority, would be compelled to take to it and maintain it. They would have the power to

lay all consequent expense on the parish in which the well is situated and to punish people who

misused or polluted the water’

Seven months later, the matter had still not been resolved. Then, on 1 July 1871, this news item was

published: ‘Hitchin Board of Guardians. More liquid poison. Mr Vincent produced a sample of

foul water from a pond by the roadside at Preston from which many of the villagers get their only

supply. It abounded with organic matter, embryo tadpoles and living animalculae and was

pronounced very bad. It was further stated that the water would become much worse if the weather

got warmer. In reply to Mr Bartlett, the Chairman, repeated the circumstances under which the

Guardians last summer thought proper to refuse to entertain Mr Weeks offer to provide a well on

Preston Green with the permission of the Lord of the Manor. He said the Board did not consider it

their duty to take to the well when complete. No order was made.’

But shortly afterwards, a solution had been agreed upon, as this notice appeared in the Hertfordshire

Express in :

Thus, although Darton may have allowed and possibly partly financed the sinking of the well, the

prime mover in its construction was Mr Weeks.

When sunk, the well was 211’ 8” deep. Two people operated the winding mechanism and they toiled

for five minutes to raise the water. The villagers appear to have become attached to its drawn water:

‘The water from the new well was considered to be very good. One young man, ill in Hitchin Hospital,

asked his old father to bring some water from Preston as he could not drink the Hitchin water. His

father spilt it on the way down so filled up his can in Hitchin, never thinking the son would know, but

when he drank it, he just turned over and died!’

Another villager remembered ’collecting water from the village pump on the green, even after mains

water was piped to the houses, because people were suspicious of piped water.’

The well was gradually accepted as a source of water. It also served as a communal news hub used

by folk as they waited for their turn to draw the water. But not many years had elapsed before this

news snippet appeared in June 1906:

This is how the well was constructed: It had an octagonal well house open at

the sides with a steep-pointed octagonal slate roof and eight chamfered

stout oak posts which are raised on concrete pads from an octagonal

Yorkstone step.

The cast-iron well gear is arranged east-west over the top of the well. It

consists of an rectangular, openwork, moulded iron trestle with battered

ends. There are longitudinal bars at half height carrying the lower axle with

another near the top with another axle and a top member swept up in a

segmental curve. Moulded braces sweep in to support the lower bar and

then intersect as cross-bracing to the upper panel. It has two large four feet

diameter flywheels with handles, one at each end of lower axle. A cog of

fifteen teeth engages a gear of ninety-six teeth on the upper axle, which also

carries a flanged iron drawing pulley. There is a larger gear of sixty teeth on the lower axle. The king-post

roof is fashioned from softwood.

Photographs show that the well was disused and fenced off by around 1930 (see above,). The well in

2012 is shown below:

Preston well c.1920

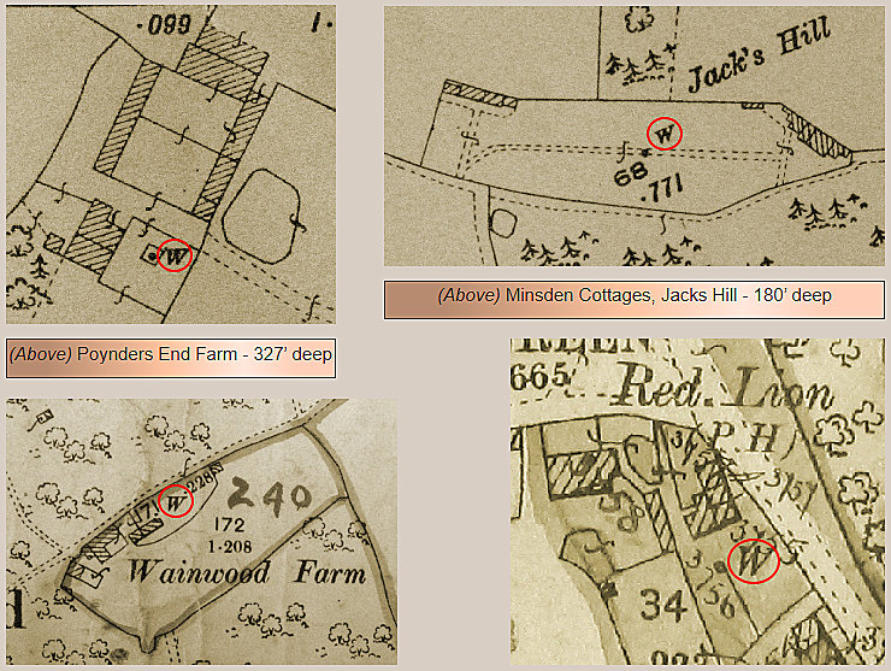

There were other wells dotted around the village which were noted on a map dated 1898:

Other wells at Preston

(Above) Minsden Cottages, Jacks Hill - 180’ deep

(Above) Poynders End Farm - 327’

deep

Bunyan’s Cottage

Cottage at School Lane

At various times there were also wells at Castle Farm, Ponds Farm, Austage End, Preston Hill Farm,

Bunyan’s Cottage and Temple Dinsley.

Robert Sunderland has kindly written to add ‘My family lived at The Wilderness from 1934 to 1961.

There is a well there not mentioned on your list. It has recently been recapped by the present owner. I

think he took my concerns over my grandfather’s concreting it over after we got mains water in 1947

seriously. ...(the well) was rough chalk-sided and about three feet in diameter. I remember it being 215

feet deep. Apparently, it was rediscovered in the late 1870’s after the then owner/tenant stuck his

pitchfork into the woodwork covering it. My guess is that it was covered over after someone fell in

many years before. Wells are rare in Preston (a long way to dig for water - ponds are easier) and the

well may be very old pre-dating the cottage and was a relic of nearby Hunsden House aka The

Castle. Butchers Lane is so-called because The Wilderness was a butcher’s shop, possibly after

being a tailor’s shop’.

Illustrating the potential dangers of sinking wells, in 1901 Edward Wilson died at Hitchin Hospital from

injuries received when he fell down a new well which was being sunk at Temple Dinsley. While he was

being lowered down, he by some means, fell off the chair and was very severely injured. He was

removed to hospital as quickly as possible and everything that could be done for him was done but he

never rallied. The deceased was a Luton man and left a widow and eleven children. The Luton Times

and Advertiser of 19 July 1901 printed this detailed report of the horrific accident:

‘An inquest held at Hitchin Hospital on Friday morning by Francis Shillitoe, Esq. Coroner touching the

death of Edward Wilson who fell down a new well while at work at Temple Dinsley on Wednesday. He

was being lowered into the new well which is over 200 feet deep. When about eighty feet from the

bottom, he either fell off or the seat came off the hook in some way. His back was broken by the fall.

The seat on which he went down is of the kind commonly used in such work. It is put on a hook at the

end of the lowering rope: and then a piece of cord is tied round the upper part of the hook so that the

ring of the seat may not be jerked out in case of a sudden stop for any cause - such, as for instance,

as the seat coming in contact from the side of the well. Wilson attached the seat himself; and it seems

that by some mistake he did not put the ring over the hook, but that it was only attached by the piece

of string, which was not strong enough to sustain his weight during the time needed to make the

descent.

The following evidence was given:

Henry Parsons said: I am a well-sinker and live at Luton. The deceased was my stepbrother. He lived

in Park Street, Luton and was employed as a well-sinker. On Wednesday I was at work with him at

Temple Dinsley, sinking a well. I had been employed there about six weeks. Two other men were also

at work there, David Crewe and John Kilby. Wilson had been working at the bottom of the well nearly

all the week. At about half past nine in the morning he was lowered into the well; he fixed the seat

himself, as he was in the habit of doing. The well is about 213 feet deep. When he was about eighty

feet from the bottom I heard him say, ‘Wo. Oh Dear’, and then he seemed to fall. When he had been

brought up, I helped to take him to the hospital. He had long experience in such work.

By the Foreman: I think he did not fall off the seat; the seat went down with him.

David Crewe said: I live in Luton and I am a well sinker. The deceased was engaged with me in

sinking a well at Temple Dinsley. He has been employed with me in similar work for about four years.

On Wednesday morning he went down at six o’clock and about half past nine he was going down

again - in doing so he fell of the seat. I was helping to lower him down. He was going down very

steadily. I do not know how he fell off. When he fell, Parsons went for help and I wound up the rope.

When it came up, I noticed that the string on the hook was broken. I had seen him put the seat on the

hook; he seemed to do it in the usual way. From the time he fell to the time he was brought up was

about half-an-hour. He did not speak when he was brought up. The hook that was on the rope had

been in use for years. I have tried spring hooks, but found they did not answer. When he fell off, we let

the seat down to the bottom of the well and it may then have unhooked itself.

James Belton said: I live at Hitchin and am a plumber in the employment of Mr Francis Newton. On

Wednesday I was at work at Temple Dinsley house, three or four minutes walk from the well. On

hearing of the accident I at once went to the spot. I found that the rope was down the well; we tried to

get it up but could not at first, either because of the injured man sitting on it or holding it. After a while

we succeeded in getting it up. I put a seat on the rope and went down. On reaching the bottom, I

found him on his back with his legs and head out of the water which was about twelve inches deep. I

secured him on the seat and sent him up. He seemed to be quite helpless. When I began to pick him

up he said he was cramped and when I put him on the seat he made a remark that I was tying him too

tight, but that was a mistake. He called out, ‘Pull up’ when I had put him on the seat. The seat I went

down on was the one from which he had fallen; how it came up I do not know; I suppose he must

have put it on the rope himself. I noticed nothing unusual in the well; there were no projections of any

importance from the side. The well was 4½ feet in diameter.

Crewe recalled said he believed the seat on which the deceased went down did not come up until

after the last witness went down. Belton said the seat on which he went down was wet as if it had

come out of the well. Parsons, recalled, said they called down to Wilson, ‘Send the seat up if you

cannot get on’ and he did so. It was on that seat that Belton went down.

Mr Richard Shillitoe, surgeon, Hitchin said: I saw Wilson at the Hospital at half-past twelve, the man in

the meantime having been seen by young Mr Foster. I found that Wilson was quite sensible. He had

no feeling in the lower extremities, but complained of great pain in his back and chest. He was

somewhat collapsed. All the symptoms pointed to his back being broken which as Mr Foster told me

was his opinion. I asked him if he could give any account of how the accident happened. He said he

could not say exactly how it happened, but he thought the seat had let him down - that the ring was

not over the hook but only fastened to it by string. That idea seemed a very plausible one. His case

was hopeless and his wife was telegraphed for. He died at ten o’clock the same evening.

The jury returned a verdict of ‘Accidental Death’ and expressed the opinion that a spring hook should

be used in attaching the seat to the rope.

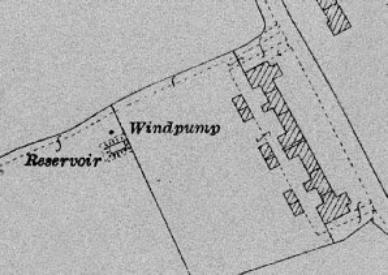

Wind-pumps

By the 1930s, the skyline of Preston was punctuated by pylonesque wind

pumps. They were used to pump water from a well into a storage reservoir

using a multi-bladed, wind turbine atop a lattice tower made of steel. They

had a large number of blades which turned slowly with considerable torque

in low wings and were self regulating in high winds.

There were wind pumps at the rear of the gardens of Chequers Cottages

(shown, far right), Poynders End, a short distance south-west of Tatmore

Place and Preston Hill Farm. They were still in use in the 1950s.

Chequers cottages

Addendum re: geological findings when Preston Green well was sunk

‘During the year 1871, a well was dug near this spot on the village green. The first sixty feet was cut

through a black gaulty soil, mixed with small particles of chalk, vegetable matter, and shells. At forty

feet below the surface, a piece of oak was found (now in the possession of Francis Lucas, Esq.), in a

good state of preservation; beneath the gault is a bed of about twenty feet of gravel and sand, after

which is the main bed of hard chalk, in which a good supply of water was found at about the depth of

220 feet.’

Handbook to Hitchin and the Neighbourhood - Charles Bishop (1875)