John Weeks - Temple Dinsley tenant, 1869 - 1879

It might be thought that the first reference to horticulture and gardening at Temple Dinsley

is the rose garden which was created by a Lutyens/Jekyll collaboration for the Fenwicks.

(Link: Rose Garden) However, there was an earlier connection when the mansion was

rented by John Weeks FRHS between 1869 and 1879.

(FRHS means Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society.) This is the story of his life.

The widow, Maria Elizabeth Darton, lived at Temple Dinsley in the 1860s. However, when she died in

April 1869, her young son and heir, Thomas Harwood Darton (born 1848) chose not to live in the

mansion – indeed he sold the estate four years later. Instead, the house was quickly rented to John

and Lucy Weeks. He was described as a ‘retired builder’ in the census of 1871.

More details have emerged about John Weeks, ‘the builder’. More precisely, he was a ‘horticultural

builder’. The Victoria County History in its section given over to ‘Farm Gardening and Market

Gardening’ in Middlesex, devoted three out of twenty-five paragraphs to John under the heading,

‘Leading Nurseries and Nurserymen’.

Of John’s parents - Edward and Catherine Weeks

John’s parents were Edward and Catherine Weeks and he was born at Chelsea in about 1808. By

1818, Edward had established a nursery on the Kings Road, Chelsea. He designed and developed a

system of heating horticultural buildings.

In July 1821, Edward, after years of manufacturing horticultural buildings, announced that he could

heat them ‘using STEAM’. He was able to supply plans for cherry houses, conservatories, graperies,

green-houses, peacheries, pineries, melon-frames and hot wall lights. As Edward narrowly avoided

bankruptcy in 1846, when it was ‘superseded’ or set aside and as later hot water, and not steam, was

used to heat Weeks’ buildings, maybe it was found that steam was not the most effective means of

warming structures.

By 1836, Edward had more fully developed the design and heating of horticultural buildings.This

branch of gardening had become popular among the rich – to place a home-grown pineapple on the

dining table or display rare plants from foreign climes was regarded as an impressive status symbol.

At Heligan in Cornwall, exotic fruits were grown using heat from decomposing straw. To have a

greenhouse heated by hot water pipes feeding from a boiler was a far more reliable option. And it

wasn’t only tropical fruits that could be produced using this method - flowers that hitherto could only

be seen in far-flung jungles could be coaxed into bloom by a combination of coal, glass and iron. New

plants grown with new technology held a fascination for the Victorians.

Under glass

In 1850, Joseph Paxton managed to persuade the giant water lily of the Amazon (with its six-foot-

wide leaves) to flower at Chatsworth House. It was grown in a glasshouse over a warm water tank

which had a paddle wheel to simulate the flow of the Amazon. The lily was christened Victoria Regia,

such was the significance of his achievement.

The specialised industry of constructing hot houses was given a huge boost in July 1851, when the

cripplingly heavy tax on glass (viewed as daylight robbery!) was abolished. Now, glasshouses need

not be small and narrow and the property of only the super rich. The ‘green shoots’ of glasshouses

and conservatories advertisements began to sprout in building supply catalogues and gardening

magazines. Now, the year round cultivation of exotic and tender plants was within the grasp of

amateur horticulturists.

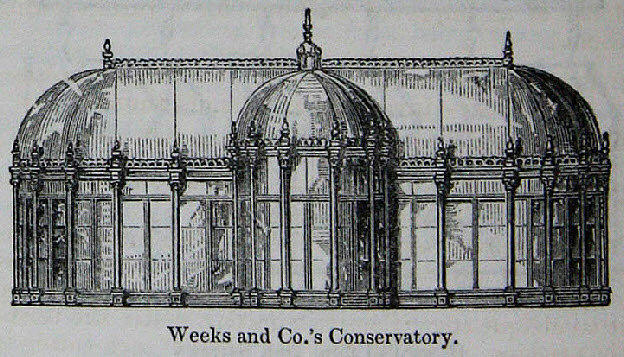

Based on his lily, Paxton designed a huge glass and modular structure to house the Great Exhibition

of 1851 – the Eden Project of the nineteenth century. Crystal Palace was opened by the Queen - and

John Weeks had his own more modest, but still impressive exhibit there. He was trading as J Weeks

and Company from the north side of Kings Road, Chelsea, at Nos. 124-126, and describing himself

as a ‘Horticultural Builder and Hotwater Apparatus Manufacturer’ – he built hot-houses and heated

them with boilers that he also produced.

The catalogue of the 1851 Exhibition includes ‘Weeks, J., and Co – Inventors and Manufacturers’.

Their exhibit was described thus: ‘Cylindrical revolving furnace bars, consuming the smoke, and

diminishing the consumption of fuel. A slow rotary movement is given to each of the cylinders, which

presents cool bars to the heat of the fire about every fifteen minutes and equally distributes the fire

throughout the furnace. Model of an ornamental conservatory with improvements in ventilation. Boiler

for rapidly heating water. Glazed light, for a common forcing-house or pit of new construction, with

improvements in ventilation. Pedestal; for warming buildings by hot water, exposing a heating area of

70 superficial feet. Stack of pipes for warming buildings by hot water, exposing a heating area of 50

superficial feet.’

From his newspaper advertisements, Weeks’ target audience is easily identified. He addressed, ‘the

nobility, gentry and (oh yes!) the public’.

During the severe winter of February 1855, his prospective patrons were invited to inspect his 1,000-

feet-long nursery, divided into forty compartments, which was heated by but one boiler. It cost no

more than 3/8d in fuel and labour a day.

In the following month of March, he boasted a ‘brilliant show of plants in flower such as cannot be

seen elsewhere. Fully showing the superiority of the houses and the hot water apparatus’.

Two years later, he had opened, ‘The Grand Winter Garden at Chelsea – the second Crystal Palace

of the day’. Now, hot water heated the equivalent of 1,300 feet of hot-houses, circulating through

7,000 feet of cast iron pipes.

Determined not to limit his market to heating hot houses, in 1860 Weeks avowed that his company

had ‘for upwards of 30 years’ been extensively engaged in warming churches, mansions,

warehouses offices etc’ and could provide references in ‘any part of the kingdom’. (Indeed, a quick

scan of documents in archives reveals there are surviving plans by J Weeks and Co for properties at

Hereford; Suffolk; Ingestre Hall, Staffordshire and Tavistock, Devon.) Horticultural buildings could be

erected ‘upon an incredibly short notice’.

He exhibited at the Chiswick Horticultural Exhibition in the summer of 1860. His contribution included

‘every form of pedestals and stacks of pipes, showing that a hot water apparatus can be made

ornamental of various designs suitable for conservatories or entrance halls. Or even for a drawing

room’. Drawings of conservatories, ‘some of very elegant design’ were also on display. Perhaps this

wording hinted at some of the objections of the nobility to his products. At another exhibition two

years later the same theme was emphasized as attention was again focused on ‘his tasteful grouping

of pipes for heated buildings. There is a well-designed pedestus for a hall, formed of tubes, and what

is termed a medieval stack for churches. Some twenty-six tubes are braced together in a double row,

forming what looks like a Venetian screen’.

Also, in 1860, the public were urged to view ‘pineapples in all stages of growth and other choice

fruits’ at his premises.

In August 1861, Mr Glenny in his newspaper column, The Garden wrote that ‘stove plants’ might be

taken out for a brief period now and suggested that then was a good time to sort out boilers and

pipes particularly if gardeners were cursed with a boiler that needed constant attention. He

suggested persuading owners to change boilers and noted that he had a boiler from Mr Weeks that

would ‘heat Westminster Hall if necessary’ and if it was properly charged and damped it would keep

water going for twelve hours. The water was heated in ‘an incredibly short time’ and in day time

required less than three inches of bright fire.

Six years later, during the winter of January 1867, Mr Glenny described Weeks’ establishment at

Chelsea. The large conservatory was ‘full of vines and choice trees in pots and it was a glorious sight

when all the choice fruits were gathered. Miles of hot water pipes were heated from one boiler. The

place is now changed to a receptacle for valuable ferns and flowering plants’ but the fashion of

growing the richest of fruits in pots like ordinary greenhouse plants had taken root.

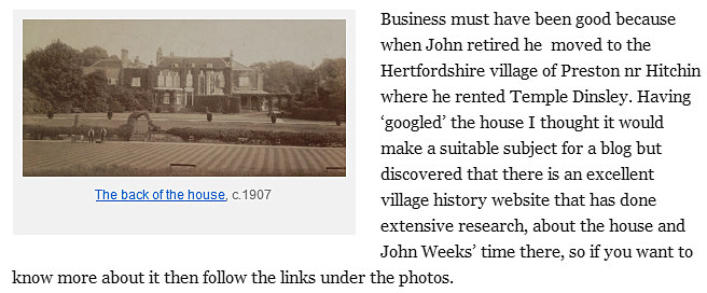

Retirement to Preston, Hertfordshire in 1869

This indication that John had interior work carried out at Temple Dinsley is of interest because when

the house was sold in 1873, it was noted that it had central heating installed. Was this by John? Do

the photographs of the interior of Temple Dinsley circa 1913 show examples of his company’s work?

(Link: Temple Dinsley)

John retired in 1869, but with his brother Alfred holding the reins, his company continued to trade. (It

became a registered company in 1897, but ceased trading in 1908.) John reserved the groom’s

cottage, coach-house and stables at the Kings Road to himself and his wife, Lucy for life but soon

after his retirement, he signed a twenty-one-year leasing agreement with Thomas Harwood Darton in

around the middle of 1869.

Map of area around Temple Dinsley leased by John Weeks

The Temple Dinsley gardens were then substantially developed by John Weeks. He was a qualified

gardener (being a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society) and designer of glass houses. He leased

the property from William Henry Darton for twenty-one years from 29 September 1869 for an annual

rent of £200.

Weeks leased about twenty-five acres which included the mansion, outbuildings, garden park and

grounds - but not Temple Farm and its fields or The Long Walk and Shrubberry beside the Hitchin

Road which led to The Cottage. These remained in William Darton’s portfolio.

The detailed map shown above has points of interest. Walls are shown as continuous lines, while

paths and two drives are shown as broken lines. Villagers working at the house had two paths to use

from School Lane. A well house beside Temple Farm is indicated and there are a cluster of

outbuildings to the north-west of the mansion. The few areas where trees are growing are depicted

and bodies of water such as ponds and the rectangular ornamental fish pond are also shown. Apart

from two small areas to the north of the house, there does not appear to be much garden planting.

Weeks’ servants and workmen were to be permitted to use the well at Temple Farm. Weeks also had

the right to shoot game, hares, partridges, rabbits and vermin. He was to keep the house ‘in a good

tenable state of repair, the gates and fences in good repair and preserve the stock of silver and gold

fish in the pond’. The garden and pleasure grounds were to be kept in good order and well stocked

with flowers, fruit and vegetables. He was not to plough any grass or meadowland (or he would incur

a fine of £100) nor cut down any trees (a fine of £20 a tree). But Weeks was not prohibited from

converting pasture, meadow or grassland into lawns and pleasure garden. He was also permitted to

make building ‘erections, fixtures and improvements’, although these would become the property of

the landlord.

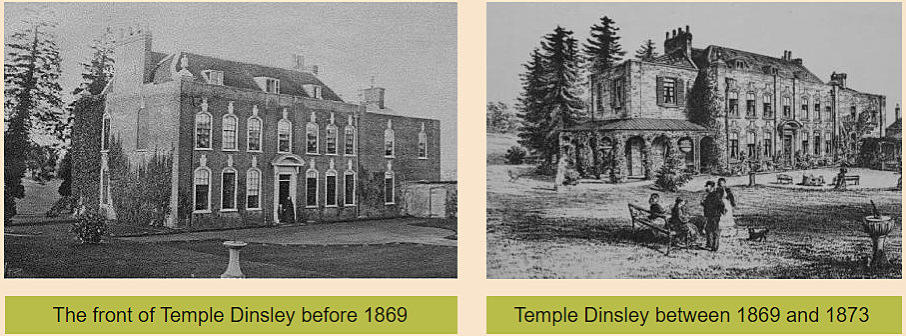

So, his was a ‘repairing lease’, and during the four years to 1873, Weeks added an extension to the

west side of Temple Dinsley, but there is no view of some of his other additions mentioned in the 1873

Sales Particulars. When Temple Dinsley was offered for sale, Weeks was still a sitting tenant.

On 2 July 1870 the local press reported a “Garden Party at Temple Dinsley”. “A brilliant and highly-

successful garden party took place on Thursday on the lawn and in the beautiful grounds of Temple

Dinsley which had been put at the disposal of a committee of gentlemen by Mr John Weeks, the

present occupier. That gentleman and Mrs Weeks, assisted by other friends, had made elaborate

preparations for the entertainment of the party which numbered about 150.

The afternoon was spent in croquet; archery, skittles, quoits and other amusements with occasional

dances on the velvet lawn. Later on, a ball took place in a magnificent tent which Mr Weeks had

caused to be erected for the occasion in front of the house and which was replete with every

accommodation; here tea and supper were served, the supply of provisions being extremely bountiful

and all excellent.

The tent and grounds besides being tastefully decorated with flowers and shrubs were lighted up at

night with many hundreds of variegated lamps and Chinese lanterns imparting a fairy-like aspect to

the animated scene. After supper, the health of Mr and Mrs Weeks was enthusiastically drunk on the

proposition of Mr Whitbread Roberts and everyone appeared delighted with the party, the pleasures

of which were prolonged without flagging until long after the day had dawned yesterday morning.”

In the census of 1871, John’s entourage at Preston included a footman and three maid servants, his

married sisters, Sarah Doyle and Rose Gainsborough and a niece, Louisa Walker. He appears to

have fallen out with the Sharp family of Preston Green. In 1870, John Sharp, (who ‘has not got as

much wit as most persons’) was charged by John with threatening to assault him. The case against

him was dismissed, not for the first time, perhaps again due to his mental deficiency. Then three

years later, John’s gardener, William Morrow was charged with assaulting John Sharp’s brother,

William (aged 16) who had worked at Temple Dinsley for 4½ years.

As John and Lucy modified the mansion another case arose: LEGGATT (plaintiff) vs. WEEKS

(defendant)

This was an action for assault and false imprisonment. There was also a count in trover for seizing

the plaintiff’s property and another for services rendered. The defendant pleaded not guilty and, as to

the assault, that the defendant was trespassing and he used no more violence in removing him than

was necessary. He also paid 15/-into court.. The plaintiff was a painter and decorator living in Little

George Street, Portman Square and the defendant formerly carried on business in Chelsea as a

builder of conservatories and greenhouses, but had now retired. In September last the plaintiff was

employed by the defendant as journeyman to assist in decorating a house at Temple Dinsley in

Hertfordshire of which he had taken the lease of a residence for his family. It seemed that a

misunderstanding arose between them and that the defendant gave the plaintiff into custody for

stealing some stencil-paper patterns which the plaintiff alleged were his own property. Having been

locked up for some time, he was brought before Mr Dashwood, a magistrate at Hitchin, by whom he

was immediately discharged.

The defence was that the plaintiff refused to leave the house when told to do so and that a policeman

was called in to remove him but that the defendant gave the policeman no authority to take him into

custody. The defendant appeared before Mr Dashwood but said he made no charge for stealing or

any charge at all against the plaintiff. The jury gave a verdict for the plaintiff – damages £50.

The images below illustrate the garden changes implemented by Weeks between 1869 and 1873 -

and also how sparse the planting was around the mansion in 1869:

John died at the mansion on 13 August 1879, leaving an estate of less than £10,000. The task of

discovering how long Lucy remained at Temple Dinsley was muddied by a reference that on

I November 1891 she also died at Temple Dinsley , though the Brands are shown in residence there

in 1881 and Mrs Brand visited Preston School regularly between 1880 and 1886.

Closer inspection of the records showed that Lucy’s death was registered at Poole in Dorset and that

she had indeed died at Temple Dinsley as she had so named her new home at Branksome Park,

Bournmouth. Her estate was valued at £24,527. Evidently, John and Lucy were childless and their

estate was administered by their niece, Louisa Doyle nee Walker who was also living on the

Branksome Park estate. Louisa was at Temple Dinsley in 1871.

Addendum

There is an encyclopaedic blog about the life of John Weeks before he arrived at Preston which I

recommend to anyone interested in the life of one of Preston’s residents.

It can be found at this link: John Weeks - life before Preston

When the writer came to describe Weeks time at Temple Dinsley, he kindly wrote the following:

John had added the glass houses to the garden and probably a vinery by 1873:

“The kitchen garden contains three newly-erected double glass houses, two measuring

40’ x 12’ 6” each and the other 4’ x 18’ fitted with hot water piping upon the most modern

principles. (clearly a Weeks’ speciality). Grapes and cucumbers were grown in these.A

vinery 94’ long in three divisions, boiler house with two boilers and furnace, fuel house,

mushroom house and potting shed.”