Introduction - Methodology

This history of Preston has been compiled after collecting every available historical reference to the

hamlet. Most of these have then been added according to their historical context. Inevitably, using this

method of research, conflicting views have been found. These have been included.

Since the twelfth century, Preston has been dominated by Temple Dinsley in its various incarnations.

Many of the Preston’s work force, male and female, worked for the incumbents. Hardly surprisingly,

much of the history of Preston is bound up with the history of Temple Dinsley.

The text, like so many historical narratives, is sprinkled with words such as, ‘likely’, ‘possibly’, maybe’,

‘perhaps’ and so on. History is not an exact science and the reader may choose to apply the

occasional pinch of salt to what has been written. I have also occasionally added my observations,

which are just that - personal observations.

This web-site is a filing cabinet of information. Links to relevant articles about Preston’s history are

provided which add considerably to the account. The articles have not been included here as they

would render this history article even longer.

To access a link, simply click the words that follow ‘Link’.

Preston’s topography and location

Preston’s topography, it’s natural features, has been unchanged for millennia.

Preston is perched on a chalk ridge of the Chiltern Hills. Over the chalk, there is a skim of clay with

flints. This drains poorly but, when ‘puddled’, ponds are formed that hold their water. This feature was

probably a crucial factor for this location being chosen as a settlement. In some places, such as Kiln

Wood, ‘brick earth’ is to be found.

The uses to which Preston’s fields were put reflected the topography. Early crops would not flourish

because the land took weeks to warm after the chill of winter. But it was worthwhile to grow root

vegetables such as turnips. Summer sowings of wheat, barley and oats were rewarding. The land was

also used extensively for grazing sheep.

Hitch Wood, Wain Wood and West Wood are today the remnants of more extensive forests which

provided fuel and food for families as well as hunting and shooting opportunities for the gentry.

One of Preston’s charms is that the village is not overlooked or dominated by hills or high ground. At

143 metres, the village is only ten metres below the highest point in Hertfordshire. The flip-side to this

sense of spaciousness is Preston’s exposure to the bleak easterly winds that sweep in seemingly

unchecked.

The first known historical reference to the place-name Preston in Hertfordshire was during an inquest of

the Knights Templar in 1185: ‘In Villa de Prestune sunt quatuor caracatae in dominio ex dono Bernardi

Balliol et partim ex dono Oliveri de Malvoier, etc.’ Translated, this reads, ‘In the village of Preston are

four carucates (although a calcucate was not a measurement of area, many authorities suggest that

this equates to around 480 acres) given by Bernard de Balliol and Oliver de Malvoier.’

To illustrate of the extent of this gift, below is an area around present-day Preston which measures

about 480 acres. But this is not intended to represent the actual dimensions of the gift - although it does

roughly conform to what many would regard as today’s Preston and its environs.

Several authorities agree that ‘Prestune’ was an Old English word. They conclude from this that this

hamlet predates the Domesday Book of 1086. Thus, Prof. Tom Williamson writes that as Preston is

derived from an Old English word, then the hamlet existed at the time of Domesday: ‘The parish of

Hitchin contains four subsidiary hamlets (including Preston) and these to judge, from their names

(which are of Old English type), were almost certainly in existence in the time of Domesday although

not mentioned in it’. He added, ‘the priest tun suggests that it was originally the portion of the estate

(of Hitchin) reserved for the sustenance of its minister priests’.

Hitchin historian, Reginald Hine, concurred. He wrote that ‘Preston’ was ‘derived from the genitive

plural of the O(ld) E(nglish) word, preost’. This meant ‘a priest’. He went on to state that it may refer to

(1) a ‘tun’ where there was a resident priest (which was such an unusual situation as to justify the

place-name, ‘Preston’ being adopted) or (2) a community of priests dwelling beside a church (which

was afterwards formed into the Preceptory of the Knights Templar) or (3) an outlying portion of the

two hides belonging to the minister of Hitchin referred to in the Domesday Book.

Thus, one may say that, historically, the hamlet of Preston probably existed before 1086 and had a

religious presence.

As to why a community became established at this location, perhaps there were two fundamental

reasons. Firstly, there was an unusual preponderance of ponds in the district because of the chalk

and clay topography. As a consequence, there was easy access to water for households, farmers and

travellers. Secondly, the hamlet was perched on the edge of the Chilterns and was therefore at one of

the highest locations in Hertfordshire. The 150-metre contour line passes through the present-day

Castle Farmhouse.

The assertion that most Prestons in England had post-Conquest foundations is at odds with the

comments noted earlier. I decided to check whether it was accurate. Wikipedia notes thirty-eight

Prestons in England - from Sussex to Somerset and to Northumberland. Bearing in mind that many of

these were small villages, how many were noted in Domesday? When I searched ‘Preston’ on the

Domesday Book on-line page of the National Archives, there were sixty-three ‘hits’, and although

several of these were duplicated, there were thirty-eight Prestons mentioned in Domesday (the same

number is a coincidence as the second set of Prestons didn’t correspond with the ‘Wikipedia thirty-

eight’). This contradicts the statement that most Prestons were “post-conquest foundations”.

I contacted Dr Tom Pickles (then Senior Lecturer in Medieval History at the University of Cheshire) in

2014 to clarify his ‘personal communication’. I referred to the document noted above and added, ‘I

would be most grateful for your further comments on this subject and any sources to which you would

direct me, please.’ He was kind enough to reply. These were his verbatim comments:

From these comments it is clear that the quote attributed to Dr. Pickles in the document was in fact

not his view - indeed, it contradicted his thinking. Therefore, in the absence of any other supporting

evidence, I suggest that the disputing document’s comment should be disregarded.

Dr Pickles also sent a copy of his 2009 academic paper (which ran to 107 pages), “Biscopes-tūn,

muneca-tūn and prēosta-tūn: dating, significance and distribution”, for which I was very grateful.

Several of his in-depth comments make for significant reading as we seek to understand the history

of Preston hamlet.

For reasons which will become obvious, I will now summarise Reginald Hine’s comments in History

of Hitchin which were based on fourteenth century manuscripts. In 758 AD, Offa fought three battles

around Hitchin. Following his final victory, he had a monastery built at Hitchin which was founded

according to the rule of St Benedict. Much of the monastery (and of Hitchin) was destroyed by fire in

910 AD. Little is known about what happened to the monks after the blaze and it is possible that St

Mary’s was built on the site of the monastery. The Domesday Book refers to the ‘monasterium’ (or

minister) of Hitchin which Hine says may refer to 1) the monastery, or 2) a college of secular priests

who served the spiritual needs of neighbouring churches, or 3) a large parish church. In any case,

Hitchin together with the Wymondleys, Ippollitts and Dinsley formed a deanery which was still in

existence in 1291 when a tax was collected to pay for a crusade.

So, from around 758 AD until at least 1291, there was a local community/communities of priests

around Hitchin - to which Dr Pickles was probably referring. There was, for example, a religious

house at Minsden, because it was mentioned in Domesday.

The thrust of Dr Pickles paper was to examine Margaret Gelling’s hypothesis that place-names

which ended in tun (such as Bishopstun, Monkstun and Prieststun) came into being in the later

Anglo-Saxon period - a belief that he declared he ‘ultimately’ supported. She suggested that this

type of place names was coined in the later Anglo Saxon period replacing earlier names for the

places to which they refer. She also asserted that a large proportion of these names were coined in

the late eighth, ninth, tenth or eleventh century as a result of the reorganisation of estates to provide

a separate endowment for bishops or for parts of a religious community.

Dr Pickles produced historical evidence that some places were named preosta-tun as early as the

seventh century. These communities might have been used for a range of purposes by the local

clergy - for food and clothing; or to provide income that would then be split into portions for individual

clerks; or it might be used as a source of communal land from which individual clerks could hold

portions whilst they were active members of the community. Dr Pickles concluded that, ‘a significant

proportion of these places, which came to be known as ‘Preston’, is known to have been owned by a

religious community or is likely to have been owned by a religious community; such associations

make an original name in the genitive plural very likely’.

In view of what is set out above as regards the religious history of the locality, it seems likely

that the hamlet of Preston, Herts was so called before Domesday - a name that reflected

religious activity in and/or around the village.

This article is not only about the place-name of Preston but when the hamlet came into being It may

have been in existence for years before it was so christened - hence Margaret Gelling’s comment

that place-names like Prestune replaced ‘earlier names for the places to which they refer’. Preston

may have been in existence for centuries before Domesday. Therefore, Wikipedia’s assertion that,

“The village grew up around the Templar holdings at Temple Dinsley” is probably incorrect.

The Norman Survey of Britain (1086) - ‘The Domesday Book’

Following the Norman invasion of 1066, it took twenty years for the government of England to adjust.

It was then time for the victorious French to meticulously assess exactly what they had conquered

and how the country should be taxed. So, a survey was commissioned in 1086. This was later

irreverently called the ‘Domesday Book’ by the sardonic English – a reference to the extraordinary

detail that was amassed, such as the Angel would compile on the Day of Judgement or Doomsday.

The list included all the woodland, pasture, millponds and fish-ponds, towns and villages. Each place

was assessed in ‘virgates’ (approximately 30 acres) or ‘hides’ . David Hey in The Oxford Companion

to Local and Family History explains that a hide was the equivalent of a caracute and that they

equated to the area of land which a team of eight oxen could plough in a year, sufficient to support a

family. It was not an exact measurement because the quality of the ploughed soil and the nature of the

terrain might vary. Hey wrote that a caracute ‘normally covered about 120 acres’.

The residents of England were classed as either villeins (free men - tenant farmers who held land in

return for the services they provide to their lords to small landowners who owned their plots outright),

cottars (cottagers) or bordars (unfree peasants with little or no land) and slaves. Rents, labour services

and plough teams were assessed to see how much money could be squeezed from the nation. Also

included in Domesday were disputes over who held land.

Although the settlement we know as ‘Preston’ likely existed in 1086, it was not mentioned in the

Domesday Book. The challenge for us is to determine which section of the document included

Preston. To do this, the following place names of the time will be discussed - Hitchin, Dinsley (aka

Deneslai) and Welei.

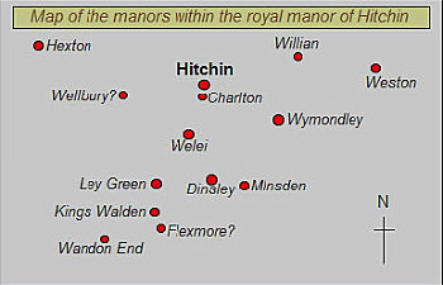

In 1086, Hitchin was a sprawling, royal manor. As well as being a manor in its own right, it was also

the centre of a cluster of fifteen smaller manors. These had a total area of more than 4,000 acres.

Here I add a clarifying word about manors - although these were administrative units, they did not

govern the same area as a parish. Manors may have been centred on a nucleus (for example, a

Manor House) but sometimes included other pockets of land some distance away.

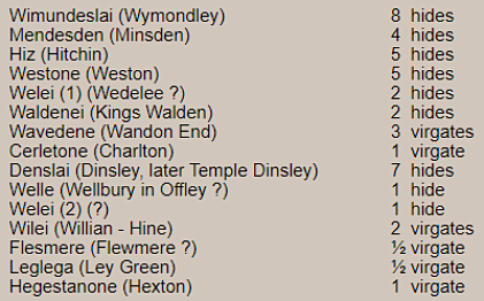

Now follows a list of the manors within the Royal Manor of Hitchin as recorded in the Domesday

Book. Please note that the second largest manor in the district was Dinsley. In brackets are the

modern place-names assigned by historian Wentworth Huyshe and agreed by Reginald Hine – the

queries indicate uncertainty of identification:

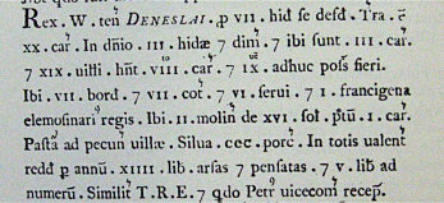

Re: Dinsley/Deneslai: The first mention of Deneslai is in Domesday. Professor Skeat asserts that

‘Dinsley’ is derived from the chieftain Dyne – Dynes Hill or Dynes Lea. However, the Hertfordshire

historian, Salmon, states, ‘Deneslai might be derived from the Danes Land, who were much in the

Hundred of Dacorum and nearer as the Six Hills (in Stevenage) convince me’. Glover attributes the

name to ‘Dyn(n)e’s clearing or wood’.

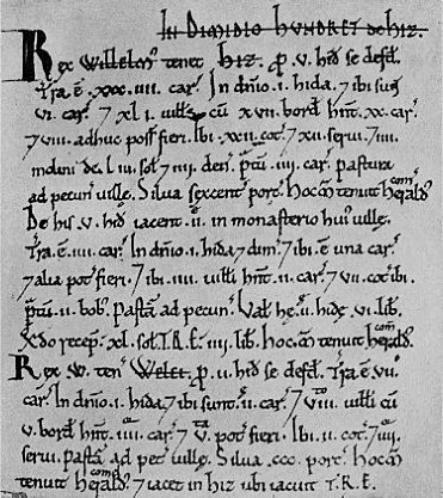

A translation of the Domesday entry for Deneslai: King William holds Deneslai. It is assessed at seven

hides (840 acres). There is land for twenty ploughs. In the demesne (the Lord’s land) there are three

and a half hides (420 acres) and three ploughs are on it and nineteen villeins have eight ploughs

between them and there could be nine more. There are seven bordars and seven cottars and six serfs

and one Frenchman (a settler from abroad, not necessarily French), a Kings almsman. Two sokemen

(free men) held this manor as two manors of Earl Harold in the time of King Edward and could sell.

Yet they each found two averae and two inwards in Hiz; but this was by injustice and by force as the

Hundred (Court) testifies. These two manors Ilbert held as one and he was seized thereof by the

King’s brief for as long as he was sheriff as the Shiremoot testifies. But after he ceased to be sheriff,

Peter de Valongies and Ralf Tailgebosch took this manor from him and attached it to Hiz because he

refused to find the avera for the Sheriff. Geoffrey de Bech, Ilberts successor, claims in regard to this

manor to have the King’s mercy.

On the basis of this information, there were approximately 180 men, women and children living in

Dinsley, inhabiting around forty houses - which surprisingly placed it in the largest 20% of settlements

recorded by Domesday.

Re: Welei : The Domesday entry for Welei indicated that there were about eighty-six people living in

the manor, occupying nineteen homes. It occupied two hides or approximately 240 acres. The area of

woodland was extensive as it supported 300 pigs who fed on acorns and beech mast.

Of Dinsley/Preston Castle

The granting of the site of Preston Castle to the Prior of Wymondley) would seem to point

to the fact that it was then either dismantled or completely destroyed, and this of course

helps to explain the entire absence of any remains of the building, for in the course of

625 years its very ruins would perish, probably having served ...as a quarry for

subsequent buildings. Its stones and beams may still exist in the old cottages at Preston.

It is possible, however, that the castle was totally destroyed by fire…. If therefore Guy de

Balliol...built the castle ...at about the time the Manor was granted to him by William

Rufus, and if the reference to the Prior of Wymondley holding the site means that it had

been destroyed by that time, the castle was in existence less than 200 years. From it

many a time, no doubt, Bernard de Balliol went to the Templars’ Mass at the Preceptory

Chpel and knelt by his father’s tomb. It is natural enough therefore that we should find

him among the benefactors of the (Templars)”.

Why build a castle here? The structure was intended to dominate the area. Preston is on a high ridge

of the Chilterns - a 150 meter contour line runs through Castle Farm. A tall castle built here would

tower above the trees of Wain Wood and be clearly seen in Hitchin and the surrounding district.

Huyshe made these additional comments about Dinsley Castle:

Preston in the Domesday Book and the Manors of Dinsley and Welei

Above, transcripts of the entries for Hitchin (Hiz), Welei and Dinsley in the Domesday Book

Preston in the Domesday Book - in which Manor did Preston lie?

In which manor was Preston included for Domesday? The surprising, short answer is that no-one

knows with certainty - but there has been considerable debate on the subject.

Historian, Wentworth Huyshe, made this point in 1906: “Welei is mentioned immediately after Hitchin in

the Domesday Book. Hitchin and Preston geographically are close.” He argued that Preston was

Welei. Hitchin historian, Reginald Hine, agreed. However, it might be argued that other settlements

such as Ippollitts and Wellhead (which were also not mentioned in Domesday) were even nearer to

Hitchin than Preston and so could have been Welei if that argument is pursued.

The Victorian County History adds to the uncertainty by stating, ‘…..Welei cannot be identified with

certainty’.

Evelyn Lord cast further doubt about the location of Welei in The Knights Templar in Britain (2002).

She suggested that it could be represented by the modern place name of Wellhead (which is close to

Hitchin).

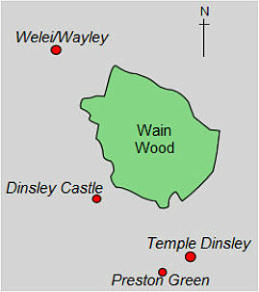

In 2002, Prof. Tom Williamson joined the discussion when he referred to ‘the vill(age) of Welei or Wilei

which comprised a large part of the later parish of Preston’. He included a map which showed Welei as

immediately south-west of Wain Wood and separate to, and to the north of, Preston.

He then added, ‘in the south of the parish of Ippollitts just to the north of the modern village of Preston

lies Wain Wood and the probable site of the lost Domesday vill(age) of Welei.’ (The Origins of

Hertfordshire). No reasons were offered for this location being assigned to Welei.

So, historians are divided over the identity of the manor which included Preston and, as the twenty-first

century has passed, the matter has become clouded rather than clarified.

However, I suggest that there is an obvious objection to the theory that Preston lay in the manor of

Welei.

A History of Preston in Hertfordshire

A detailed history of Preston: Part one

A pond near Castle Farm, Preston

However, the conclusion that Preston, Herts existed before 1086 because of the Old-English origins of

its place-name was challenged in 2010 by a locally-sourced piece which stated:

Preston in the Domesday Book and The Royal Manor of Hitchin

For this reason, Preston was likely included in the manor of

Dinsley (which was of seven hides or around 840 [7 x 120] acres).

This conclusion may be corroborated firstly by the names given to

In Domesday, Welei consisted of two hides which equated to

approximately 240 acres. But, as discussed earlier, around a

century later Preston occupied an area of four carucates or

around 480 [4 x 120] acres.

Thus, Preston was twice the size of the Manor of Welei which was

assessed at two hides in Domesday. Preston could hardly lie in a

manor which was half its size.

The reader will have noticed the use of words in this account such as ‘would seem’, ‘may’, ‘if’, and ‘no

doubt’. These comments appear to be his conclusions which may or may not be accurate and are

unfortunate as they may dilute the impact of the proof that Preston Castle existed.

Reginald Hine also indulges in similar whimsical wonderings in his Early History of Temple Dinsley by

writing in a typical flowery style: ‘These Balliols belong not so much to the parish of Hitchin and to the

castle of Dinsley as to this realm of England’. ‘...no cry comes across the centuries from those who

rotted in the dungeons of the Balliols...(who) cursed the cruel castle of Deneslai..’ ‘the castle of Dinsley

which, when the Balliols were banished, was brought into ruin and rented by the Prior of Wymondley at

a mere 10s by the year’. Again, we read a historical fact which is embellished with fanciful details.

Additionally, in the chapter of Hitchin Worthies that features Robert Hinde, Hine also asserted that

there was a manuscript, History of Hitchin, in St Albans Museum which mentions the remains of

Dinsley Castle and stated that ‘the keep, bastion and curtain walling of the castle’ could be seen in

Robert Hinde’s time (around 1750)’.

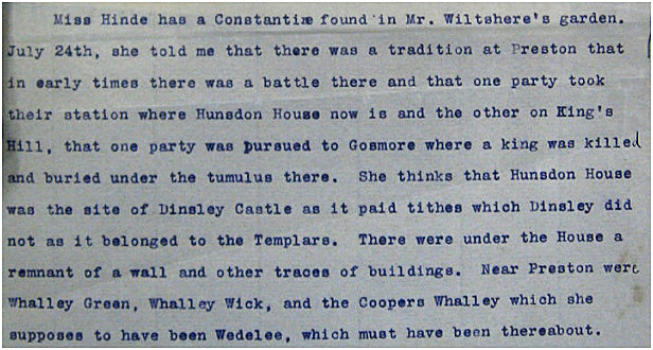

At the same time he wrote that there was a tradition related by a Mrs Hinde of Preston ‘that in early

times there was a battle there; that one party took their station where Hunsdon Hall (aka Castle Farm)

is now and the other on Kings Hill, that one party was pursued to Gosmore where a king was killed and

buried under a tumulus there.

Confirmation of this story is to be found in the London Guildhall library where in 1902 EA Downman

had lodged some plans of these earthworks.

After some email correspondence, this manuscript of collected notes was traced to Hertfordshire

Archives and the relevant part is now shown:

Finally, there is the possibilty of a well within Dinsley Castle to consider. It most certainly would have

had a well which, in addition to daily needs, would have provided water supply in time of siege. At

Porchester Castle, for example, there is the well in the keep of the Norman Castle (see below

left).There is a well on the Preston site - “a three-hundred-feet deep well which is thought to be the

original well of Preston Castle”. It is capped and hidden by a playhouse/shed, but if this is the well that

was within Preston Castle it is possibly the oldest existing landmark in Preston’s history (below right):

Bernard de Balliol 1130 - 1153

Earlier in this article, we discussed the gifts which were given to the French Baron, Guy de Balliol

following the Norman Conquest of Britain. On his death, these were inherited by his cousin, Bernard

de Balliol. The latter appears to have had considerably more dealings with Hitchin and Dinsley than

his uncle. This is illustrated by the gift at Preston that Bernard in turn bestowed upon the Knights

Templar (who will be discussed in the next part of this history).

Here is a catalogue of gifts bestowed on the Templars between 1142 and 1149:

1142. King Stephen granted rights and privileges (but not land) on the Templar’s

holding at Dinsley. As it was only rights and privileges that were bestowed, it is

probable that Stephen had already given some land to the Templars here – remember

that Dinsley was in the King’s hand, being described as a ‘royal manor’ in Domesday.

1142. King Stephen confirmed an earlier grant of an acre at Dinsley (called Smith

Holes) that John Chamberlain had granted to the Templars.

In late 1142, Stephen gave the Templars 40 shillings worth of land at Dinsley as well as

two mills and ‘the men of the land’.

April 1147. Bernard de Balliol gave the Templars 15 librates of land (about 450 [15 x

30] acres) called Wedelee which was in his manor of Hitchin. This grant took place at

a Chapter of the Templars in Paris around Easter-time. Present were the King of

France, four archbishops and one hundred and thirty Knights who were ‘arrayed in

white cloaks’ in what must have been breathtaking assembly. Alluding to the practice of

smoothing the way to heaven, Bernard declared that, ‘....for the Salvation of my Soul, I

have given...(to the Templars) fifteen librates of my land...Wedelee by name which is a

member of Hitchin; fields rough and smooth, streams with woodland.’ ‘This grant

was.... made under unusual circumstances which seem to emphasize the importance

of the gift’.

April 1147-49. King Stephen confirmed a gift of uncultivated land (‘waste’) in Dinsley.

Now, for the first and only known time the place-name ‘Wedelee’ is introduced. The location of this

place has been the subject of more debate among historians interested in Hertfordshire.

In 1906, Wentworth Huyshe pointed out that thirty-eight years after this gift, in 1185, the possessions

of the Knights Templar included Preston (which amounted to four caracates, about 480 acres). He

argued, that on the basis of this, Wedelee and Preston were one and the same place. Reginald Hine

agreed.

Victorian County History states that, ‘Welei is possibly (my italics) Wedelee in Preston, but both this

and Welei cannot be identified with certainty’. It adds that Wedelee was ‘a name used elsewhere for

Dinsley’ (although no footnote is included to support this statement).

In The Place Names of Hertfordshire (1936) J E Glover claims that Wedelee is one and the same as

Welei, because ‘the medial ‘d’ in Wedelee is a common Anglo-Norman eccentricity’.

In 2002, Evelyn Lord suggested that Wedelee could be represented by the modern place name of

Wellhead (which is close to Hitchin).

I agree with the Victorian County History that Wedelee is one and the same as Dinsley (ie not

Preston, but including Preston) simply because of the extent of the land (about 450 acres) it

encompassed. Remember that in 1185 the first historical mention of ‘Prestune’ stated that it had an

area of approximately 480 acres - considerably less than the 1147 gift. So the additional land mass

bestowed on the Templars may well have included other local property - in later centuries, the Manor

of Temple Dinsley included Wayley (sic) and parts of Wymondley and Offley. Research!

The importance of this gift (and therefore Dinsley and Preston) to Bernard is shown by the occasion

of its being given and the audience who witnessed it. We have already mentioned that Bernard’s

interment was in the chapel (at Temple Dinsley) and that he was probably often in residence at the

castle at Preston which, Huyshe believed, was built by him.

A picture thus emerges of Bernard’s attachment to Dinsley. It was fitting that his effigy be lodged so

close to this area in the Church of the the Royal Manor of Hitchin, St Marys (see below).

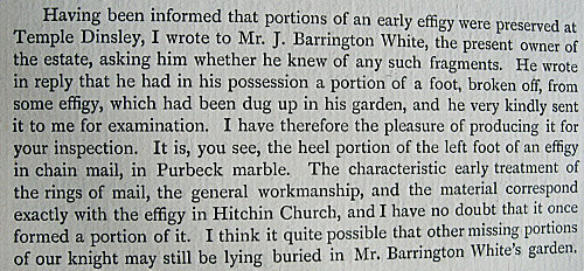

Huyshe had much to say about this effigy in 1906. He writes “If you enter Hitchin Church by the south

porch and cross over to the north aisle of the nave you will see, lying on the sill of the westernmost

window, a mutilated, recumbent effigy of Purbeck marble, the face ground away, the legs broken off

below the knees…it is one of the earliest (effigies) in England, much resembling…some of the

famous effigies in the Temple Church in London.

“Salmon, writing in 1728, says of the early effigy in Hitchin Church and of two others…’They are said

to have been brought from Temple Dinsley when the Chapel was pulled down’….Mr F S

Clarkson…comes to the conclusion that it was executed somewhat earlier than the close of…1189

and that whether the effigy was brought from Temple Dinsley or not ‘all the local circumstances are in

favour of its being the memorial of Bernard de Balliol who founded the House of the Templars there.

“Since Mr Clarkson wrote in 1885, the discovery in the grounds of Temple Dinsley of a fragment of

the foot of a knight in chain mail seems to set the matter at rest once for all….in 1903 I made the

following observations upon it:

“I made diligent enquiry as to the precise place where the fragment was found, but without success.

Mr Frederick MacMillan, who lived at Temple Dinsley before Mr Barrington-White, tells me that in his

time it was one of several fragments of worked stone which were in the garden on the surface

forming part of an ornamental rockery”

Kings Hill Plantation at the bottom of

Preston Hill illustrates the local chalk strata.

The flints and clay in this field beside the

Kings Walden Road are typical of the area

The origins of Preston and its place-name

the Temple and Castle which were built in the vicinity of Preston in the twelfth century - ie Temple

Dinsley and Dinsley Castle and secondly, by the fact that much of Preston was still in the Manor of

Temple Dinsley in the seventeenth century.

“Subsequent gifts from King Stephen, who confirmed the Balliol grant, and others in Kings

Walden and Charlton created a substantial estate, and a Preceptory was established at

Dinsley, hence Temple Dinsley, by 1185, at which date the adjacent place-name Preston (the

Priest’s farm) is first mentioned.

There is no discrepancy in Preston being a Post-Conquest foundation despite the Saxon

name (it is not mentioned in Domesday, though Wedelee (not so, PJW) and Dinsley are);

there are many Prestons in England, and most have been shown to be Post-Conquest

foundations (pers comm Tom Pickles) (ie from personal communication with Tom Pickles).”

1. Coining: I think a lot of the place-names Preston (preosta-tun, 'the estate of the priests') were

coined in the later-eighth, ninth, tenth or early-eleventh centuries, i.e. pre-Conquest in the Anglo-

Saxon period. I think this was so because it was common for abbots/abbesses of religious

communities to hold all the land before the later eighth century, when we start to see groups of

priests holding some of the community's land for their own use; because the majority of these

names existed by Domesday Book (1086 - 1088); and because very few applied to estates in the

hands of priests after 1066. So they seem likely to belong to the period between the mid-eighth

century and the mid-eleventh century. But some may be post-1066, of course.

2. Meaning: I think they referred to land set aside for the use of priests - I explore some

possibilities for their use in the paper.

3. Social Context: I think the land was set aside and the names were coined for it when an

existing religious community was taken over and reorganised, often by a king or bishop.

4. Hitchin: Though I did not consider Hitchin as a case study, it may be a pre-1066 community of

clergy, part of whose land (the preosta-tun) was set aside for the priests for a specific purpose. I

seem to recall off the top of my head that Hitchin was a small community of priests in the

Domesday Book?

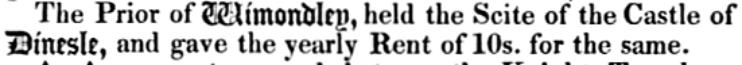

A historical document confirms that there was a castle at Dinsley or Preston. This is an indisputable

fact. Chauncey in his Historical Antiquities of Hertfordshire (1700) wrote:

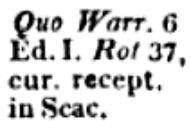

This refers to the ‘site of the Castle of Dinesle’. Chauncey also cited a reference to this document:

When Edward 1 returned to England in 1274, he ordered a general enquiry

into the misconduct of local government and the misuse of franchises. All

owners of property were required to prove their right to it after being served

a writ of Quo Warranto. ‘6 Ed 1’ refers to the Statute of Gloucester 1278

and ‘Rot’ means that the property was restored by the king, the precise

reference being ‘37’. A copy of this is held in The National Archives.

It is probable that Wentworth Huyshe in The Royal Manor of Hitchin (1906) was referring to this

document when he wrote, “(Bernard de Balliol II, Junior) would no doubt have been present at his

father’s interment in the chapel (at Temple Dinsley) and was probably often in residence at the castle

at Preston which, I believe, was built by him close to the Templars’ establishment. The site of Preston

castle is about 650 yards distant from Temple Dinsley. I find it on record that in the year 1278, the

Prior of Wymondley was in possession of the site of the Castle of Preston at a yearly rent of 10/-” He

added, “I have not been able as yet to find any direct reference to Preston Castle except that which I

have mentioned, in the year 1278”.

Huyshe mentions Bernard de Balliol in his piece and the relevance of the Balliol family to Dinsley

Castle is now explained. The French baron, Guy de Balliol played a prominent part in the invasion of

Britain and was rewarded with swathes of land in the northern part of the new kingdom. One of the

first priorities for the conquerors was to impose themselves on the natives, to head off any retaliatory

uprising and cement their powers of administration. As a result, during the next fifty years or so, they

built castles - many so grand and so sturdily built that they survive a millennium later.

In 1094, William Rufus granted Guy de Balliol the enormous estate of Bywell in Northumberland. He

only occasionally spent time in Britain – enough to cause a writ to be produced prohibiting him from

hunting on another’s land – preferring to stay in France. It is reported that he ‘began the construction

of a ring-work defence’ at what is now Barnard’s Castle before the Castle was actually built.

As well as his northern estate, Guy was also granted land in Hertfordshire. Surprisingly, the only

reference to this is dated more than 350 years after the gift was made – and its content must be

inferred. The Cottonian Manuscript of 1463 records that previously, de Balliol’s widow gave the

brothers of St Albans monastery ‘one virgate of land in Hehstantune (ie Hexton, Herts)’. It has been

reasoned that if it was in the power of the Balliols to make this grant, then it follows that they must

have been given the land. Since Hexton was within the Royal Manor of Hitchin, it has also inferred

that the entire Manor was included in this gift, part of which was Dinsley and Preston. On a mere two

lines in a document written centuries after the event such suggestions have been hung hung!

There is some corroboration of this in Testa de Nevill (1234/35) in which Hugh de Balliol was said to

hold Hitchin – it being the gift of Henry III.

Meanwhile, Guy died on an unknown date. His heir was his cousin, Bernard de Balliol I (senior), who

succeeded to his uncle’s estates sometime between 1112 and 1130. Now we have the Preston

connection, for it is Bernard’s Purbeck marble effigy which was discovered at Temple Dinsley and

now reclines by a window at St Mary’s, Hitchin. Here we have concrete (or marbled) proof of

Bernard’s attachment to the area.

Returning to the subject of castles and their part in the

subjection of hostile natives (who included the Scots),

Bernard built one of the grandest Norman castles

overlooking the River Tees at what is now known as

Bernard’s or Barnards Castle (see right):

As the Balliols so imposed themselves in

Northumberland, they did likewise near Hitchin. They

built Deneslei/Dinsley Castle at Preston on the site of

what today is known as Castle Farm.

Here, there is only a mention of a ‘remnant of a wall and other traces of buildings’, and the words ‘the

keep, bastion and curtain walling’ are not included - but it makes for interesting, if misleading, reading!

Much as one might distrust folk-lore in general (such as the villagers’ belief that Joseph Darton was

the son of Miss Martha Ithell and Thomas Harwood), it would be unsurprising that stories about a

castle at Preston would be promulgated. In her Scrapbook History of Preston, Mrs Maybrick wrote,

“Dinsley Castle, which probably had previously been a pre-historic stronghold and stood on the site of

what is now Castle Farm, was held by the Balliols and the Templars, and from it they dominated and

overawed the countryside”. Sylvia Beamon wrote in The Royston Cave, “Dinsley Castle, which

probably had been previously a prehistoric stronghold and stood on the site of what is now Castle

Farm, was held by the Balliols and the Templars, and from it dominated the countryside.” It might be

suggested that she was either quoting from the Scrapbook, or that both had found the same authority.

Whatever the case, these statements are probably an echo of a long-standing tradition in Preston

that there had been a castle at the village, although the suggestion that it was “previously a

pre-historic stronghold” may be questioned.

Before we leave the subject of folk-lore and Preston Castle, volume 46 of Revue de Literature

Comparee comments of Robert Hinde, “...(he) remodelled his grandfather’s house to make it fit in with

the surrounding ruins of Dinsley Castle and probably also to gratify his own inclination for things

military (or perhaps for the dawning fad of things Gothic)”.

In summary, a case can be made that there was a castle at Preston on the basis of an existing

document dated 1278, there is a local tradition of folk-lore which refers to it and its well may still exist

One last aside: in 1869, Mrs Elizabeth Mayle of Dunham, Beds presented a medieval (ie dated 1066 -

1485) chafing dish to the Society of Antiquarians which was found on the site of Preston Castle.