A History of Preston in Hertfordshire

The Nuns of Elstow

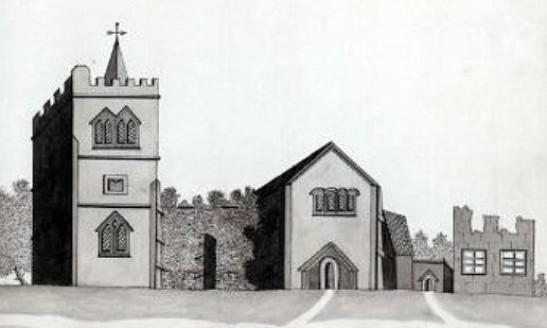

Elstow Church with the remains of the Abbey

To comprehend what happened at Preston/Dinsley a millennium ago, we need to time-travel back

further thousand years.

The title ‘early Church fathers’ perhaps conjures a mental picture of venerable old and very wise men

earnestly poring over Scriptures to distil their meaning in order to produce tenets by which generations

of Christians were to live.

Unfortunately, they were fallible. Some of their teachings were flawed.

Take for example Augustine of Hippo, an ‘influencer of influencers’ who is venerated as ‘one of the

greatest saints ever’. He was ‘a man constantly responding to questions from others about wealth and

the afterlife’.

These enquiries were related to texts such as 1 Timothy 6:17-19 and Matt 6:19-21 which encourage

the rich to put their hope on God, to do good works and share generously ‘thus storing up for

themselves the treasure of a good foundation for the future’.

The rich wanted to know what benefits might accrue to them if they transferred all or part of their

treasure to heaven. Augustine effectively groomed them. He preached the need to give alms for the

care of the poor, the support of the clergy and the building and maintenance of churches.

For many wealthy landowners this was interpreted as the need to gift swathes of land to monasteries

and nunneries in the hope that their own souls would be saved by the act of taking out these after-life

insurance policies. This was manna from heaven for monks and abbots as they received land and

therefore rent from their tenants every year which made them both rich and powerful. In The Common

Stream, Rowland Parker refers to this as ‘a misunderstanding or deliberate misinterpretation of the

Gospel message’. For many, this control was only broken by the dissolution of the monasteries by

Henry VIII several centuries later.

To illustrate the mindset of the wealthy, Parker draws on the example of the second wife of Edgar, King

of Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria who founded a Benedictine nunnery at Chatteris, Cambs in

around 975 AD because ‘of pure piety, or for the salvation of her soul, or because it was the

fashionable thing to do’. He adds, ‘Her case was typical of many. All over England, abbots, priors and

abbesses were acquiring…vast estates made up entirely of gifts “for the good of my soul and the souls

of my ancestors”’.

In the twenty-first century this teaching is now outmoded - Augustine’s doctrine has been diluted. A

quick trawl of the internet for explanations of how Christian’s may store up treasures in heaven include:

introduce yourself to a visitor or unfamiliar face at church; pay for the person behind you at the drive-

through; tell someone that ‘God loves you’; smile at a stranger and leave an especially great tip for

your server and an encouraging note. These actions are a far cry from Augustine’s stance but they

illustrate how difficult it has become for a person of today to understand the motives behind the

behaviour of the rich a thousand years ago.

Turning now to the nuns of Elstree, their acquisition of a nunnery was somewhat different because the

gift was partly made because of Judith’s loyalty to her half-brother, William the Conqueror. This is how

it came to pass:-

Countess Judith founded the Roman Catholic Benedictine Abbey of Elstow, Bedfordshire in 1078. She

was born in 1054/55 and was the half-sister of William the Conqueror and the widow of Waltheof, Earl

of Northampton and Huntingdon. She had holdings of land in ten English counties.

Waltheof and his brother conspired with the Danes to subvert the newly-established English dynasty of

William only three years after his conquest of England. When this uprising failed, he submitted to the

King who, in response, confirmed his rights as Earl and gave him his niece, Judith, in marriage. In

1074, he declined pressure to join with another conspiracy against the absent King but promised not to

betray the plotters. However, Judith learnt of the revolt, told William, and as a result Waltheof was first

imprisoned at Winchester and then beheaded in 1075. It was possibly as a reaction of contrition and

atonement for her part in the death of her husband that Judith built Elstow Abbey. The Abbey was

noted in the Domesday Book of 1086.

A Royal Charter was a formal document issued by the sovereign which

granted rights and privileges to individuals or organisations. Between 1124

and 1135, a Charter of William’s successor, Henry I, legally confirmed an

earlier gift of ‘the Church of St Andrew, Hiche (ie Hitchin) with lands and

liberties’.

Rev SR Wigram in his book, “Chronicles of the Abbey of Elstow” (on which

this article is primarily based) suggests that the Church at Hitchin was

undergoing the process of conveyance either to the Abbey or to Judith who

may have made them over to the Abbey at the time the materials for the

Domesday Survey were being collected. St Andrews Church was annexed

to St Mary of Elstow and its name gradually morphed from Church of the

Nuns of St Mary to St Mary’s Church.

Another Royal Charter passed between 1130 and 1160 during the reign of

Henry II confirmed several new gifts conferred on Judith in Hertfordshire.

These included:

A Benedictine Nun

37 “Of the gift of Maleverer and Cecilia his wife, the Church of Dumeslai (sic) and six

acres of land in the same vill(age).”

38 “Of the gift of Roger de Chandos and by Grant of Robert his son (who came to

England during the Conquest) the whole land which he had in Dineleshou”

‘Dumeslai’ and ‘Dineleshou’ likely refer to Dinsley - some decades later, in 1185, the inquest of the

Knights Templar recorded ‘In the village of Prestune are four carucates (around 480 acres) given by

Bernard de Balliol (who had died by 1167 and Oliver de Malvoier (sic).’

Then, during the reign of Henry III, there was an agreement between Almeric de St Maur, Master of the

(Templar’s) Temple and Mabilia, Abbess of Elstow for the provision of a chaplain for the chapel at

Preston. Three Charters alluded to this during the rule of Henry III in around 1218/19:

“Covenant between the Masters and Brothers of the Temple and the Abbess of Elmestowe

concerning tithes in Hichen (sic) and the annual payment of one mark of silver”. The

Brothers were to pay the Nuns tithes of corn in the parish of Hitchin and also the tithes of

all newly-tilled lands, men and assizes at the time of this covenant. The nuns granted that

the Templars at Preston in the parish of Hitchin have a chaplain to be selected by

themselves to celebrate divine service for them throughout the year at the appointed times

(ie three days a week - Wednesday, Friday and Sunday - celebrating Mass, Matins and

Vespers). The nuns for the support of this chaplain shall give the brothers one mark of

silver: one half at the feast of St Michael and the other half at Easter - and four pounds of

wax at the feast of St Michael.”

These documents are also of interest as they contain only the second-known historical reference to the

place-name, Preston.

By 1533, the holding of the Rectory of Hitchin, including Preston/Dinsley, accounted for around half the

income of the nuns. It was assessed at £66 13s 4d out of a total holding of less than £128. The Abbey

was a casualty of the Dissolution of Henry VIII and was closed in 1539, when it was transferred to Trinity

College, Cambridge. Thus, one monarch gave; and another, took away.

So, during four centuries from around 1086, the dominant religion at Dinsley, and therefore Preston,

was Roman Catholicism.

The ruins of the Abbey