Site map

A History of Preston in Hertfordshire

A History of Stagenhoe: Correspondence between

Michael Dewar and Reginald L Hine 1934/35

1811c

At Hertfordshire Archives and Local Studies (HALS: Ref 71038A) there is a bundle of letters

between Michael Dewar (MD), his secretary D Curwen (DC) and Reginald Hine (RH) between

1934 and 1935 which describe how the History of Stagenhoe was commissioned and produced.

It outlines a valuable description of the steps necessary for a successful business proposition

which may be of interest to those who wish to follow a similar path.

Included are comments which may explain or highlight what was written.

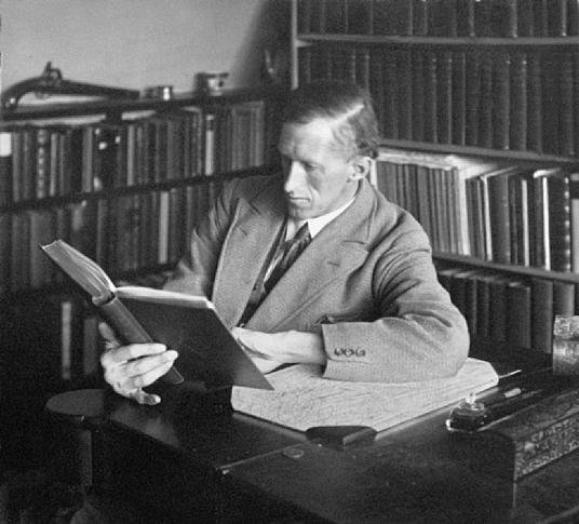

Michael Dewar (l), Reginald Hine and Richard Whitmore

Some background information

In 1932, Dorothy Dewar, Michael’s wife purchased

Stagenhoe House (shown right) and estate in Hertfordshire.

Michael was Chairman of British Timken which manufactured

bearings which were used in a variety of applications and

which prospered in the late 1930s (Link: Dewar) .

Hine’s (Link: Hine) situation in late 1934 was that although a

member of the legal profession, until July 1933 he had been

earning a modest wage as a solicitor’s clerk dividing his time

between his work and his interest in history.

The opening gambit and Dewar’s reply

From a later comment it seems that Hine had not met Dewar before they exchanged letters. However,

it is possible that their wives were acquainted as both were local Girl Guides District Commisioners in

1935. The first known contact between Dewar and Hine was on 28 October 1934, when Hine sent

Dewar a letter and some of his books. Maybe what he wrote was the catalyst for Hine’s writing the

History of Stagenhoe. Although a copy of that letter is not in the bundle at HALS, because its contents

are mentioned in other letters, some, if not all, of the items which were sent with it are known.

A listing of the printed sources of the history of Stagenhoe was included in the letter, together with

‘particulars of History of Hitchin and Hitchin Worthies’. As the letter and its contents appear to have

resulted in the commission to write the history, it is possible that securing that work was a reason for

Hine sending the package. Rather than this being in some way vulgar, it was common practice in

those days for solicitors and writers alike to look for work, which was acceptable.

Hine was quite capable of bringing pressure to bear on people when it suited his purposes. Whitmore

relates an occasion when Hine submitted an early book, Dreams and the Way of Dreams, to a

publisher, only to be told that a report by literary critic, Darrell Figgis, led to the publishers rejecting his

book. In Confessions of an Uncommon Attorney, Hine wrote that he ‘was furious’ and caught the first

train to London to confront Figgis in his home. According to Hine, the result of this meeting was that

Figgis wrote a ‘much more acceptable report - one that was to ensure the publication of my book’.

After mulling over the matter for around two months (and possibly over Christmas), on New Year’s

Day 1935 Dewar expressed his interest in the History of Stagenhoe being researched and written -

this, despite the increasingly important business affairs that he oversaw.

Despite recently publishing the three books that made his name, he then declared that he had ‘made

no money whatsoever from his books’. When Natural History of the Hitchin Region (of which he was

essentially editor, contributing only an introduction) was published in late 1934, with expensive

production costs including a special map which cost almost half of the total cost of the book to

produce, it was sold for 7s 6d. This was approximately a third of its real cost, the shortfall being made

up by the Ransoms and the Seebohms, prominent Quaker families at Hitchin.

Hine inherited no real wealth from his family. It was his wife, Florence, who enjoyed any inheritance,

being the grand-daughter of George Pyman, founder of the Pyman Shipping Group who made his

fortune from shipping coal. In July 1933, Hine passed his law examination and was admitted as a

solicitor, but he was not invited to become a partner at Hawkins, becoming instead a salaried

assistant solicitor.

Whitmore suggests that in 1932, after the publication of the trilogy of books, History of Hitchin - Vols 1

& 2 and Hitchin Worthies, Hine was ‘on the brink of a nervous breakdown’. During the 1930s, Hine’s

major works had been completed and he appeared becalmed as a writer, content with copying and

pasting various sections of History of Hitchin in a revamped booklet form.

In addition to this brief appraisal of his situation, he and his family had moved house to Willian, Herts

in the early 1930s and his only daughter, Felicity, had obtained a place at an Oxford University.

I should mention that I am not aware of any other new commissions being accepted by Hine. It is also

surprising that Hine’s biographer appears to have been unaware of the Stagenhoe piece and the

correspondence which accompanied it. He makes no mention of it or Dewar in The Ghosts of

Reginald Hine.

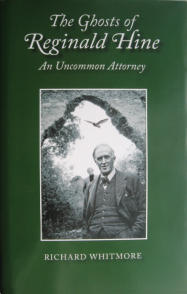

This article includes several references to Richard Whitmore’s biography

of Reginald Hine, The Ghosts of Reginald Hine - An Uncommon

Attorney.

Despite the sometimes candid, personal and unflattering image of Hine

which is portrayed therein, it was published with a chapter written by

Hine’s eldest grandson, Andrew McEwen, who wrote of the desire to

understand his grandfather better. One might assume that what

Whitmore wrote was acceptable to McEwen.

I have dipped into Whitmore’s well-written and detailed book because

perhaps his comments explain and embellish some of what occurred

during Hine and Dewar’s interaction.

Those who are inclined to write family or local history might find it useful to consider the important

question that Hine next raised with Dewar. He asked, what form should the history take? Should it be

1) a collection of copies of documents in chronological order that related to the estate and then

bound within a Book of Stagenhoe or 2) would Dewar prefer Hine to write an historical account of the

estate which could either be bound up in typescript, or printed for private circulation? The answer to

these questions was essential to be agreed upon before even an estimate of cost could be given.

It will be noted that there was no discussion whatsoever of the assignment of copyright re: History of

Stagenhoe and there is no ‘All rights reserved’ notice in any copy that I’ve seen. This, despite the fact

that Hine was legally trained and that Dewar owned a printing press.

It is worth noting that Hine was sometimes criticised for the order in which he presented the subjects

of his books and what he included and excluded. For instance, W Branch once opined, ‘...the general

arrangement of the two Hitchin volumes are curious echoes of the Victoria County History of

Hertfordshire...the manor, church, the priory, all receive their separate chapters...to bind them

together into a coherent picture of Hitchin development’.

Hine also requested sight of the title deeds of the estate. He wrote that Dewar’s solicitors may have

custody of these, especially the earlier ones, and (even more) especially the relevant Court Rolls

which would be important for the information they contained. However, these were often retained by

the vendor or their solicitors.

He also suggested that he might ‘turn up early drawings and paintings of the mansion and its

owners’. Might Mr Bailey Hawkins help here? In addition, Hine submitted that he could obtain the

view of Stagenhoe in Chauncy’s History of Hertfordshire and also a ‘careful’ enlargement of Buckler’s

drawing dated 1832 which was in St Albans Abbey. This is a reminder that in 1935 it was not as

simple as it is today to make a copy of an original document.

From his office at 10 Mayfair Place, London W1, he wrote ‘I should very much like to have some

research work done on Stagenhoe. Could you give me some idea as to what it would cost and

whether you would be prepared to undertake it? I should like to try and find some old drawings and

prints there are of it, and its real history. I hope in the summer to open up the secret passage which Mr

Baillie Hawkins tells me exists, and if possible to follow it to its end.’

Dewar’s early enquiry as to the cost involved is not surprising. This is often the concern of those

requesting that research work should be started and is maybe a sign that they do not fully understand

the complexity of the research task. It also perhaps demonstrates Dewar’s cautious, business-like

nature - which was to manifest itself more than once, as we will see.

At the same time on 2 January 1935, Dewar’s secretary wrote to Hine asking from whence he could

obtain History of Hitchin and Hitchin Worthies because they appeared to be unobtainable - a request

with which many writers of local history will be familiar even in these days of Abebooks on the internet.

The speed displayed by Hine’s response to Dewar’s interest is a testament not only to the postal

service of the day, but also how he was drawn to the research task ahead. The day he received

Dewar’s letter, on 2 January 1935, he replied ‘I am glad you feel disposed to have some research

done into the history of Stagenhoe and of its successive owners. It is a work that should have been

undertaken years, if not centuries ago; and the results should add to your enjoyment of the property

and be of definite value if ever you decided to sell’.

Hine was here expressing a genuine desire - even a passion, to carry out this research. He highlighted

the potential economic benefits of documenting Stagenhoe’s history and was evidently attempting to

persuade Dewar to complete the commission while also reassuring him of his capability to undertake

the research.

Hine then addressed the subject of his fee, saying that it was hard to give even a rough estimate

because he didn’t know precisely what Dewar wanted and therefore suggested a meeting ‘…either in

Town or at Stagenhoe itself. Preferably on a Sunday morning or afternoon when I am more my own

master, or at Mayfair Place almost any evening after 6.15, or at or after lunch time at Stagenhoe any

day’.

One might conclude from this classic ‘either/or’ approach to securing an appointment, that Hine’s diary

was less than full and that he was keen to clinch the assignment. Dewar’s secretary had mentioned

that Dewar would like copies of the printed sources of the estate’s history to add to his library and Hine

would be pleased to assist him ‘if he was still of that mind’.

A commitment to deep research and an accurate report

Hine emphasised the enormity of the assignment and also tacitly provided an assurance that the piece

would be accurate by explaining that this research would involve the labour and cost of sifting through

Hertfordshire’s stacks. He would search for manuscripts relating to Stagenhoe - ‘Patent Rolls, Close

Rolls, Domestic State Papers, Assize Rolls and Papers, Pipe Rolls, Inquisitions, Charter Rolls,

Quarter Session Rolls, Manor and Court Rolls, wills, feoffments and Title Deeds, Household Account

Books, Diaries, letters etc. It means turning over some thousands of documents, but I am inclined to

think it would be worthwhile and you would at any rate know that every possible avenue of information

had been explored. A mere casual or surface browsing over the obvious sources would hardly be

worth undertaking.’ Perhaps such a long catalogue of sources was unnecessary.

This passage is reminiscent of Hine’s comments when he penned the History of Hitchin. He wrote of

hundreds of thousands of documents ‘that had first of all to be discovered and disinterred; and not in

one parish or county and country, but in many parishes, counties and countries...the records of your

parish will be scattered over the face of the earth; and even in your own soil you need to dig not one

spit deep but two. Small things and tiny parishes, slipping more easily through nooks and crannies of

time, sink deeper into oblivion.’

He would become not an ‘historical artisan but an historical artist. Building up, if you can, an authentic

picture of the past; assembling your innumerable isolated facts of every conceivable colour, fitting,

joining, compacting them together into a preordained design’. Here, Hine is expressing a commitment

to the thoroughness and challenging nature of his research and a willingness to deeply delve into the

hidden crevasses of archives and museums. It is shorthand for, ‘this will be expensive, but

scrupulously veracious’.

It is therefore odd that History of Stagenhoe includes sections that contain incorrect details which

could have been resolved by properly conducted research. (For a detailed example, use this link:

Caithness’ car and scroll down to Addendum) Whitmore briefly comments on being ‘surprised to find

that, despite Hine’s claims of carefully wading through (thousands of documents), there are a good

number of factual errors in his books’. He offers no explanation for this. He merely quotes a curator of

Hitchin Museum saying that Hine, ‘frequently stretched the bounds of probability in the interests of

telling a good story’.

Is it sufficient to believe this was the reason for his imprecise prose? Perhaps he deliberately

described events erroneously because this version was what he thought his readers wanted to hear?

And, how does knowing that he was to be well-rewarded by Dewar for his work allow him to describe

events falsely? Perhaps the accounts of his hoaxes (of a buried ‘artefact’ supposedly of great antiquity

and the ghostly apparition at Minsden Chapel) reveal a conscious flirting with truth which contradicts

his publicly expressed desire to dig two spits to discover and divulge that truth.

The method to be used when writing the History of Stagenhoe

2 January 1935 - Hine’s reply and the ’fourth book of Hitchin’

A copy of Hine’s handwritten reply is included in the deposit. It reveals that the typing of his letter was

probably produced by some one other than Hine as ‘Chauncy’ and ‘Buckler’ were carefully spelt out

(by the typist?) in capital letters, thinking maybe along the lines of, ‘must not misspell these names’ -

Hine’s handwriting was notoriously hard to read.

Hine then added, ‘Now that I have finished ‘Hitchin’ (the fourth volume was published last month), I

could, I think, find time to undertake what you suggest.’

Taken at face value, it is not obvious to which book Hine is referring when he states that the fourth

volume of Hitchin was published last month. However, we are helped by a review of The Natural

History of the Hitchin Region in the Hertfordshire Advertiser which described book (first published in

December 1934) as “his fourth and last Hitchin book…the completion of a historical survey of Hitchin

which he undertook twenty years ago”. This appears to be the fourth book in a series which included;

A Short History of St Mary’s, Hitchin (first published in 1930, 40 pages), The History of Hitchin

Grammar School (1931, 68 pages), and The Story of Methodism (in Hitchin) (1934, 16 pages).

Natural History wasn’t Hine’s ‘last Hitchin book’ by any means. The Story of the Sun Hotel (Hitchin)

(1937, 24 pages) and The Story of Hitchin Town (Football Club, 1938) followed later. Two more

booklets were published in 1946, which largely contained photographs. Most of these books consisted

of re-hashed sections from his History of Hitchin.

As to the reason that these slim volumes were published, they may have been requested by

interested parties. They were far cheaper than the History of Hitchin (which meant that they were

within the means of more readers) and they kept Hine’s name in the public eye. Although Natural

History contained little of his writing, it was his name that was trumpeted when it was published. Luton

News commented, ‘Mr Hine’s only contribution to the book is the historical introduction…we wish he

could have written more…such as comments about ancient trees’.

If these booklets are taken out of the picture, Hine did not write any books apart from Stagenhoe for

the fourteen years between the release of Hitchin Worthies (1932) until Confessions of an Un-

Common Attorney (1946) - which further suggests that when he wrote to Dewar, he was actively

seeking a commission.

4 January 1935: Dewar’s reply, a meeting is arranged and a fee is discussed

The essential minutiae of the research process: collating relevant documents

Hine was aware that Dewar’s son-in-law would not be keen about Hine’s handling the more recent

deeds, so copies would suffice. In any case, it was the earlier documents that he particularly wanted

to see - they had only an ‘antiquarian value and could be safely entrusted to a Fellow of the Society of

Antiquaries like me’. Though Whitmore describes a later meeting which Hine attended when he was

stopped from leaving the room with a rare rolled-up map under his arm - ‘Well, bless me! I seem to

have it here under my arm’.

He was still focused on viewing the older deeds, and because of the concern of their holders

suggested that although he would prefer to work in his own library, possibly they could be taken to

Stagenhoe from whence he could collect them, giving a receipt for their safe custody. Unless there

were a number of Court Rolls, he would only need them for one month.

Hine also requested that Henry Whitehead’s collections should be sent to him immediately, so that he

didn’t ‘double up’ on his researches - he had already written to the British Museum and the Public

Record Office, where he would be working the following Saturday. This was no chore or hardship.

Whitmore commented that these places were ‘his favourite places of research and relaxation’ and

were ‘less than an hour’s journey by rail’ from his new home. There ‘he could occasionally meet some

of the literary figures of his day’.

In addition, Hine had written to the curators of the Museums of Hertford, St Albans, Welwyn Garden

City and Letchworth asking that a list of their holdings relating to Stagenhoe found in their card indices

be sent to him.

From Stagenhoe, Dewar acknowledged receipt of Hine’s letter on 4 January 1935 and wrote a

lengthy reply the following day. He suggested the two meet at Mayfair Place either next Sunday

morning or, failing that, the following Sunday. He asked Hine to obtain copies of the works Hine had

previously listed and confirmed he wanted both the types of report that Hine has mentioned (1 and 2

above). He would seek the location of the title deeds and Court Rolls, adding that Sir Henry

Whitehead’s butler had said that his master had some work undertaken. Additionally, he was writing

to Whitehead’s solicitor to ascertain exactly what was done.

Hine attended the first meeting mentioned, remarking that it was a pleasure to make direct (and the

first?) contact with Dewar and his family. He went to considerable lengths to express his fascination

with Stagenhoe as a subject - he declined subjects that didn’t interest him as without that appeal

‘there can be no heart, no keenness, in any kind of work’. He had taken ‘an immediate liking to

Stagenhoe and its owner and the estate was beautifully placed’, all of which was perhaps intended to

be music to Dewar’s ears. Maybe the Templar’s treasure would be found, though he was sceptical

about the possibility.

Regarding his fee, Dewar’s good-natured consent not to “tie him down to a month or two” and his

evident interest in the history of the estate decided Hine to say, “Yes”. He would send a draft

estimate, and if both agreed he would draw up an agreement in duplicate which both could sign over

a six-penny stamp. After the contracts had been signed, they could be exchanged and both could feel

“legally bound”. The common sense displayed by Hine in taking this course is commendable - there

was no taking the word of an officer and a gentleman.

Serendipity smiles on Hine - always a welcome intervention

Hine also reported a stroke of luck. He had found a portion of the original account of the rebuilding of

Stagenhoe in 1660, in the handwriting of William Hale’s steward. This was in private hands.

With almost a hint of triumph, he outlined how he had recalled that papers had been purchased by a

dealer in Hove and had been subsequently disposed of. Hine had ‘hunted down these precious items

yesterday, and had them on loan’ and would seek instructions about acquiring them for Dewar.

With an eye to publication…

Hine wanted to dovetail original documents, coats of arms, photographs of charters into ‘your

Stagenhoe book’. This indicated that Hine was already contemplating how the History of Stagenhoe

might be presented. However, as we shall see, there was no attempt to incorporate any original

documents in the book. If there were any further copies of the History, then they would have to be

photographed.

If Dewar decided to print the History on his Broadway Press, the needed blocks could be prepared

from them. The following Saturday, he was hoping to see some thirteenth century charters and

recommended that they be reproduced as well as the Domesday Book entry. However, (having

evidently sized up his client) he assured Dewar that costs would be reported to him before any order

was made.

In Hine’s mind’s eye, it seems that he was considering the possibility of the Stagenhoe History being

‘properly’ published - not the two or three type-written works that we have today.

Hine then made an enquiry which is worth noting: he wanted to “humanise” his history of the estate

and “make it more readable” by using biographical notes of the successive owners and portray the

lives they led at Stagenhoe. As it happened, he had “a rich collection of Hertfordshire biography” and

was acquainted with the records of the Stagenhoe owners as Justices of the Peace, including some

handled cases in the Justices Room in the Stagenhoe mansion which made for interesting reading.

It will no doubt have struck the reader that these letters describe a master class of how to make the

initial preparations when writing local history, which is well worth reviewing. Such books should not be

‘dry’ historical pieces but ‘readable’ - a quality which was highlighted when his History of Hitchin was

reviewed. Country Life: ‘A very engaging story as well as a painstaking antiquarian document...The

past is vivid; the bones of old account books are clothed in flesh and blood, so they fill the stage as a

thrilling drama’. Spectator magazine: ‘Local historians seldom contrive to be both informing and

readable. Mr. Hine's new work on Hitchin is a brilliant exception to the rule. He has collected a mass

of most valuable details from the local and national records and other sources, and yet he never

forgets that a history is meant to be read by ordinary people.’ As his Stagenhoe researches had

expanded and were now coming to a conclusion, Hine felt that he could sign his part of the contract

immediately and invited Dewar to follow suit.

A lesson in making local history books more readable

Dewar’s secretary, D Curwen, becomes increasingly involved with the correspondence

On 1 February 1935, Curwen sent Hine his master’s signed agreement. He also confirmed that

Dewar’s solicitors did not hold any Court Rolls and wrote to suggest that Hine visited Mayfair Place to

see the Title Deeds perhaps on Friday, 8 February. In the meantime, did he want Curwen to send the

old Deeds or wait until he was next at Dewar’s office?

Then, on 11 February, Curwen contacted Mrs Burke, Lady Whitehead’s daughter, at Ilkley, Yorks, to

ascertain whether Lady Whitehead had ever asked about investigating the history of Stagenhoe;

whether there were any portraits of previous owners of Stagenhoe available for purchase and whether

she knew of the whereabouts of the Court Rolls of Stagenhoe. Mrs Burke returned the letter with

pithy three ‘No’s beside the questions.

The following day, Curwen informed Hine of the letter that he had written to Mrs Burke and furnished

the addresses Hine had requested: of Lord Feversham (re: the Court Rolls) and Lord Caithness.

These had been copied from ‘Who’s Who’ - though one might wonder why had Hine had not used that

reference book at Hitchin. Curwen also wrote that he had been attempting to contact Sir Arthur

Sullivan’s executors and had been told that Sullivan had not married and had no descendants - a

nephew who was the only beneficiary having himself died.

The speed of exchange of letters was slowing now, as fewer issues needed to be resolved. Dewar

agreed that estate maps could be detached from the Title Deeds and framed; that the Revd. Henry

Rogers be visited at Norwich and wondered if photographs of the mansion and Domesday Book

facsimiles could be seen by Mr or Mrs Dewar before purchasing them. Dewar was taking other

photographs home to show Mrs Dewar.

In March and April 1935, only details needed to be discussed

As the letters begin to deal mainly with less important matters, only brief descriptions of their

contents in March and April 1935 will be presented:

7 March 1935 MD to RH: MD would like photographs of pictures of previous owners of Stagenhoe

but didn’t want to go to any unnecessary expense. He also wanted a meeting with Hine to ‘talk about

how things were going’.

7 March DC to RH: MD had kept three large and one small photograph - ‘put them on his account’.

He was returning four small photographs of the garden.

15 March MD to RH: Cheque sent for RH’s expenses - £7 2s 9d. His Expenses Book was returned.

This was an exceptional controlling of expenses. Was Dewar simply applying sound business

principles to their dealings or was he concerned about how far Hine’s enthusiasm might lead him?

13 April MD to RH: MD was returning the book of photographs borrowed from Henry Rogers. He

wanted eight copied together with three stereoscopic (sic) photographs sent with this letter.

17 April MD to RH: Lord Derby had no information. All the family’s papers were destroyed ‘at the

time of the revolution’. However, the next day Lord Derby’s secretary sent a list of documents that

referred to Stagenhoe.

26 April DC to RH: MD’s secretary notified Hine that he had sent a cheque for £5 2s 6d directly to

Latchmores, presumably in payment of photography work that had been carried out.

Now there is a break in the correspondence that has been retained and stored at HALS - though one

doubts that this reflected an actual cessation of letters. As Timken’s profits were growing, due to

dramatic advances in production techniques, it is possible that Dewar’s time was more occupied by

increased business pressures. But a press release around this time by Dewar tends to suggest that

this was not necessarily the case, as is next described.

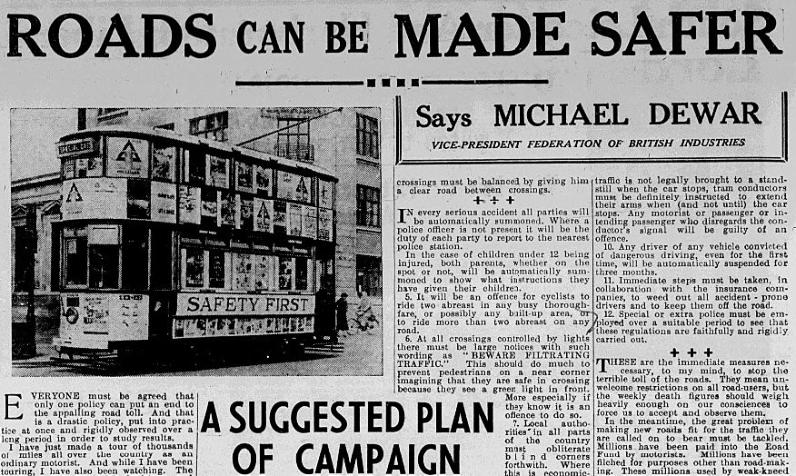

At the end of October 1935, Dewar had written an article about reducing road casualties as a result of

his observations of traffic and people on the roads of Europe. The historical context for this is that the

compulsory driving test was introduced in England on 1st June 1935, for all drivers who started

driving on or after 1st of April 1934. There is a Pathe newsreel film devoted to the new test which is

narrated by Sir Malcolm Campbell (who didn’t have a great record for driving safely). (Link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BbbERUEsQ4Q&ab_channel=FordHeritage).

October 1935 - Dewar’s newspaper article re: Road Safety

Dewar’s article was probably syndicated in several newspapers - examples have been found in the

Leicester Mercury and Glasgow’s Sunday Post. If he had time to write and arrange for its distribution,

finding time to deal with Stagenhoe history matters maybe was not an pressing issue for him.

26 November 1935 - The focus is now on finalising details re: Hine’s report

26 November 1935, RH to MD: Hine wrote, ‘The good work on Stagenhoe goes forward and I get

so interested in it that I cannot keep it as short as I intended. It seems a pity to scrap many of the

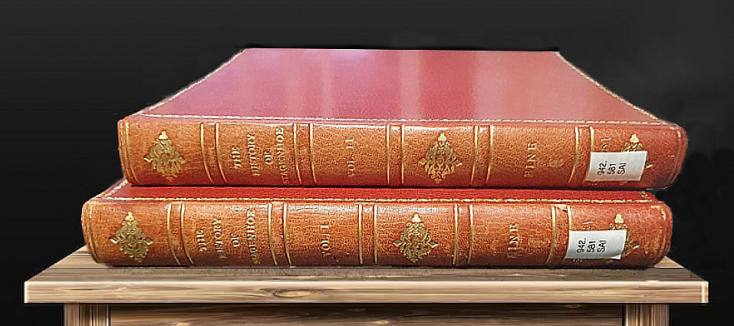

best finds I have made. I hope to have the typescript bound up in two volumes by my friend Douglas

Cockerell (who has just bound up Codex Siniaticus) and shall have taken delivery of Volume 1 at the

end of January, and Volume 2, at the end of February. 120 pages already typed. I have chosen

paper of the quarto size after all as it is easier to handle and to read, and to make it easier still, I

have typed in triple spacing and on good stout paper.’ Did Hine actually do the typing?

These are absorbing details. Hine was well-known for his interest in how his books were presented,

which was not appreciated by the printers. Whitmore observed that Hine ‘insisted on controlling

every step of the operation of publication’ of one of his books.

‘The typeface, the ornate drop letters at the start of each chapter, the expensive paper, the gilt

edges, the special inks, the presenting of illustrations and the elaborate blocking of the binding - all

were (Hine’s) personal choice and reflected his delight in the look of 17th-century books’.

There were more comments in this letter that invite consideration. Hine wrote, ‘Well, at the turn of the

year I am leaving Hawkins where I have been for thirty-five years and am (with the consent and

actually with the assistance of that friendly firm) setting up for myself at 109 Bancroft, Hitchin. I have

delightful offices in what is left of Frederic Seebohm’s house and though I shall spend the last week or

so dusting my office furniture (it will be worth dusting - period stuff!), I hope to succeed in time. I shall

at least carry with me the good wishes of my many friends.’

Hine’s language indicates that only one copy was bound at that time. He wrote, ‘I hope to have the

transcript bound up’. Chris, HALS Chief Archivist, has kindly informed me that Hine had two copies of

the History bound - one by Cockerell, the second by Paternoster and Hales of Hitchin. It is the latter

copy in two volumes (shown below) that has been languishing in the rare books stacks at HALS

since 12 December 1976, according to a note in a volume. Chris adds that there is a comment from

Hine (c.1940) that the original typescript was at Stagenhoe. Is one exhibiting an ignorance of 1935

binding techniques when one queries why two volumes were necessary? Or was this an unilateral,

executive decision?

Hine reported that on 26 November 1935, 120 pages had been typed. The final figure was 25%

more, weighing in at 150 pages - but the sum paid remained as agreed despite the additional work.

Hine’s comments re: leaving Hawkins solicitors for Harding, Hine and Co.

It is difficult to conclude whether here Hine was expressing a self-delusive viewpoint or presenting the

spin of a popular writer/solicitor. Whitmore devotes considerable time to discussing how Hine was

regarded by his Hawkins’ colleagues and their reaction to his leaving - a whole chapter in fact, Times

of Change. ‘I’m afraid Mr Hine is not very popular in the office. He had a room to himself and instead

of working for the firm he spent all his time on his books’. This is probably exaggerated, but conveys

frustration. Another blunt reflection; ‘In the end the partners got pretty sick of Hine…My

understanding is that he was virtually turfed out of the firm in the end’.

13 July 1936 C to RH: MD’s secretary sent a cheque for £250 for payment in full on completion of

History of Stagenhoe plus final expenses of £6 11s 0d. Hine had asked whether the book would be

offered for ‘private circulation and the somewhat curt response was that Mr Dewar was so

exceptionally busy that he couldn’t consider the matter but later on perhaps the matter would be

brought up again. Hine was thanked for the signed copy of his book which he had given to the

secretary.

While ‘the histories…took twenty years to research and write’, from its conception in early January

1935, to receiving payment (presumably at its birth), the History of Stagenhoe occupied less than

seventeen months to produce.

13 July 1936: Hine is paid for History of Stagenhoe and wonders how it will be circulated

I’ve been in this position myself on more than one occasion when, having spent a long time writing a

lengthy report for a client, I’ve learnt that they had only got around to reading it many months after it

had been delivered. Even when one has been paid for the work, the feeling that one’s efforts have not

been appreciated is not soothed. I wonder how Hine reacted to the news that Dewar had only just

noticed that photographs were not included in the book he had in his possession for three months.

Hine’s reply is not in the bundle, but on 21 October 1936 Dewar wrote to Hine, “Thank you so much for

securing me the photographs. I am paying the account direct. By the way, I did send the photographs

back to Miss Baillie-Hawkins. I have every intention of having the History of Stagenhoe printed next

year, provided I have got enough money. PS Would you mind letting me have back the cutting I sent

you of Lord Caithness’s ‘motor car’, as I have forgotten the address.” Hindsight indicates that it wasn’t

money that prevented the History being printed.

12 October 1936: Dewar’s final concern

There the matter lay. Hine had moved on to new projects when he received a letter from a somewhat

agitated Dewar, dated 12 October 1936. ‘I have read and re-read the second volume of Stagenhoe

with great interest. To my horror, I find you say that all the nice photographs taken are being kept in

the Stagenhoe records. I am afraid that up to date they most certainly are not. I should very much like

to have them all put in a book so that they may be kept alongside your written record.’

In conclusion, this record of correspondence is fascinating on so many levels. Not least, Hine’s

working methods as he prepared, researched, wrote and finally had two copies typed and bound are

exemplary. Nina Freebody wrote that she was aware of three copies. No-one I’ve contacted among

Dewar’s descendants appear to be aware of its existence - nor did Whitmore or McEwen.

We do not know at present what happened to the original copy of the History which was delivered to

Dewar. This was a time of upheaval in the Dewar family. After his wife’s death and the end of WW2,

Michael soon left Stagenhoe. He re-married, but died shortly afterwards and his widow quickly

moved from their home. The History appears to have disappeared from sight . When another History

was commissioned by the new owners in 1982, it might be presumed that it was no longer at

Stagenhoe.

Conclusion

The History of Stagenhoe by Reginald L Hine

‘1. Derivation of the names Stagenhoe and Walden

It is a time-honoured custom amongst antiquaries to begin the history of a place with a dissertation

upon its name, and, if one hesitates at all, it is because so often one has to feel one’s way along and

write in a subjunctive mood. Those who have threaded the mazes of philology know there is no more

hazardous domain; each step is littered with the bones of early explorers.

Fortunately, with a name like Stagenhoe, one is not driven into a wilderness of guessing. One can

write out of a blessed assurance and in the indicative mood. There was a time when a wrongful

derivation was current in these parts. The Rev. H. Hall in his Names of Places in Hertfordshire (1902,

p 9) traced Stagenhoe from the Anglo-Saxon Staegar - a path and hoe - a hill, and a certain

plausibility lent to this theory by the fact that the ancient British track, later and still known as the St

Alban’s Highway, ran over the hill, and right across the estate. But soon a greater that the Rev. H.

Hall arose.

In 1904 there appeared The Place-Names of Hertfordshire by the Rev. W.W. Skeat, Prof. of Anglo-

Saxon in the University of Cambridge. In this more scientific work, which at once superceded Hall’s, it

is shown that the ‘g’ in Stagenhou, which is the Domesday form of the word, is hard, and must

therefore have been double in Angle-Saxon. The form suggests Stacgens - Staggens, the generative

plural of the weak Stacga or Stagga, meaning ‘a stag’. This place-name is of considerable

importance because the Anglo-Saxon word for stag is only known from a single passage in the Laws

of Cnut (No. 24) “Sed si regalem feram quam angli staggon appelant”.

The offices of Hawkins and

Co, Hitchin

109 Bancroft, Hitchin, the offices of Harding, Hine and Co

in the centre of the image

Whitmore describes the hoaxes in detail without examining the psychological reasons for playing

them. They are considered to be the deliberate acts of fabricating falsehoods to deceive others,

which reveal the hoaxer as often viewing their victims as gullible and their self-perception as being

intellectually superior - a form of narcissism. Hoaxers can minimise the harm caused by their actions,

by thinking ‘no one was really harmed’ which enables them to maintain a self-image as morally

upright individuals. Hine did not appear to have learned any lessons after being black-balled by the E

Herts. Archaeological Transactions Society because of his first hoax.

Stagenhoe lies in the parish of St Paul’s Walden, which before the Dissolution of the Monastries was

known as Abbot’s Walden, and in the pre-Norman period as simply Walden. Over the derivation of this

name also there has been a battle of the books. Some scholars, remembering that this part of

Hertfordshire was Royal forest held that Walden was so styled from Anglo-Saxon weald - a wood.

Others, with less warrant, connected it with A.S. Weall - a wall. But the spelling of the name as it

appears in the Hundred Rolls, viz Weledene, should have given them a clue. Weala is the genitive

plural of wealth - a stranger or foreigner, more especially a Briton or Welshman. The sense therefore is

‘Valley of the strangers’ or ‘Valley of the Britons’. Here as at King’s Walden and Walsworth (wealas-

garth) you find traces of the original inhabitants, Iberians, Celts, Britons, who by the successive

invasion of Romans, Saxons and Danes were driven out of their settlements into hiding places and

haunts of ancient peace; some of them as here, to lie down by the still waters of the Mimram or hunt

for food and climb for safety, like stags, upon the woodland hills.’

For a full discussion of this subject see Skeat’s work as cited, pp. 36-7; and Thorpe’s Ancient Laws

1, 429. The English Place-Name Society has not yet published its volume on Herts, but the Secretary,

Prof. Alan Mawer, whom I have consulted, states that he has nothing to add to or qualify in Skeat’s

derivation of Stagenhoe.

1

(NB This short transcription of pages from The History of Stagenhoe by Reginald L Hine is featured

for non-commercial research and to illustrate the essence of the volume, to encourage interest in it

which may result in its being read, should it ever be published.)

To complete the story, a brief, transcribed extract of the History of Stagenhoe now follows as a

published work for the first time:

Conclusion

It is good to have ransacked the last library, to have scanned the last manuscript, to have filed the last

portfolio away. Even to a thorough-going historian there is more in life and history than these, and my

writer, once his labours are accomplished, will long to escape to the dense undergrowth of detail out

of the clearing and lift up his eyes unto the hills. To compose these valedictory lines I have stolen

away from my abode of books at Willian and have found a marvellously mossy bank on the edge of

Chalkley’s Wood. It is good to lie here in delicious ease and in a golden sunny haze to watch the

precession, the dream-reverie of Stagenhoe history as it winds slowly down the valley and away.

Looking upon the pageant of a thousand years, with all its colour, the rich mosaic of its past, the

chronicled memories of poignant happenings, one has a blessed feeling of content. Surely it was

worth while after all, to devote twelve hard but happy months to the history of such a place!

Sometimes I think one is more profitably employed on these works of smaller scale. You may write the

history of a market town, as I have done in several volumes, but it is difficult to marshal all your facts

and drive them before you like a flock of sheep, down the highway of the centuries. And towns

strangely even in a lifetime, as I sadly know.

With a little estate it is different. You can measure and master it. You can see it as I see it now, almost

in a glance. You can walk round it in the compass of an hour. You can grow familiar with every brick

and tile, every tree and every common bush. You can trace each footprint of its history. Moreover, you

will learn in time to love it, as you love a child, just because it is so small.

And then too, one has the blessed assurance that one has been writing all the time of something that

will not pass away. Men and women strut for their brief hour across the stage of life and disappear.

Towns are built, un-built and re-built. Land remains.

Land is real estate, and real not only in the legal connotation of that term, but in common parlance, as

of something that stands firm amidst the passing shows of this transitory life. It is not with land as it is

with houses and with those that inhabit them. Broad acres do not bear the scars of old unhappy far-off

things and battled long ago. The serfs and villeins and copy-holders who ‘swinked and sweated’ for

themselves and for their lords of Stagenhoe upon the open fields have in turn been harried by the

Danes, conquered by the Normans, oppressed by local barons, decimated by the Black Death,

disillusioned by the Peasants Revolt, suffered the pricks of wounds and death in the Wars of the

Roses, been persecuted for their religious faith , made to fight for their liberties in the civil war, have

impressed as soldiers for the wars in France an known the fears and doubts of these modern

disastrous days. In their records, as I have endeavoured to show, the historian can follow the

vicissitudes of the Verduns, the Pilkington, the Stanleys, the Hales, all of whom suffered the

ship-wreck of their lives.

But land is an almost incorporeal hereditament, in that nothing – no ravage of war, no violence of

man, no plague, no famine – can, save for a brief season, disturb its natural loveliness and

productivity. In the trade of armies, runs the proverb, are lean years, but seed time and harvest do not

fail. However bad the times, the peasant goes forth to his labour till the evening. Dame Nature smiles;

the spring returns; the winter of man’s discontent is gone.

Yes; fortunate are they who have such a piece of England for their possession. In a world too

dangerously civilised it should help them to get back a little to the wild, to roam the hills and dales like

the stag that first found its place of refuge at Stagenhoe, and in the midst of ‘Waldene - the valley of

strangers’, to settle down in an English home.

FINIS

Finally, one cannot leave this subject without describing a talk that Hine gave at Stagenhoe - at least

that is what it appears to be. It is a type-written Short History of Stagenhoe and includes his comment

of being ‘pressed for time’; his thanks to Mr and Mrs Dewar for allowing them to be at Stagenhoe

House and that ‘later today, in a few minutes, we shall be at St Paul’s Walden Church’.

In one extraordinary paragraph, he recounts the tradition ‘that the owner of Temple Dinsley has the

right to to stand on the front door-step of Stagenhoe on Christmas Day and fire off a gun. Next

Christmas Day, I intend to come over with Miss Prain (headmistress of the newly-arrived Princess

Helena College) of Temple Dinsley and re-establish that custom and, incidentally, I shall take care that

she holds the gun at right angles and does not blow Mr Dewar to bits’.

1

A consequence of writing to all and sundry when gathering information is the

occasional, sharp riposte. On 15 January 1935, Dewar was duly informed by

Lady Whitehead’s solicitor that the only historical facts of which she is aware

was a list of people who had inhabited Stagenhoe Park since 1102. A list of

these was sent to him when he purchased the estate. (Ouch!) However, the

letter had an enclosure of a drawing of the stained glass window which was

described at the end of the list of occupants, a second copy of which was sent.

As Hine had re-visited the matter of an agreement, on 21 January, Dewar wrote

back to say that he would like a clause inserted about expenditure on travelling

expenses and research work that would ‘protect’ him. One might wonder why he

felt the need for such protection.

The next letter from Hine (shown right) was dated 29 January 1935, as a result

of which Dewar’s secretary, Curwen, sent a list of deeds held by the bank,

asking which ones Hine required. The reader may have noticed that Curwen is

featuring more and more in this correspondence. This time, a reason might

have been that Dewar was occupied with arrangements for his daughter,

Joan’s, wedding at Marylebone, London on 31 January 1935.