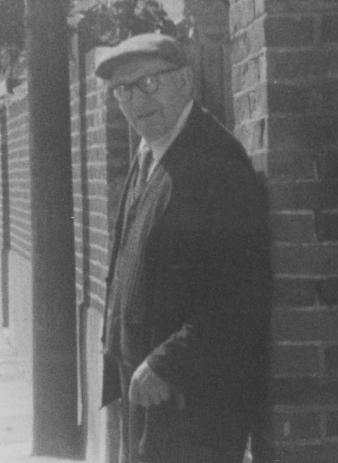

Father: Sam Wray (born 1905)

Sam (certainly not Samuel) was the thirteenth child of Alfred and Emily Wray. He was born at Back

Lane, Preston, Hertfordshire on 30 July 1905. Later, when retirement was looming, this was to be a

surprise to him. He sent for a short copy of his birth certificate which indicated he had toiled a year

longer than necessary! He thought he had been born in 1906. The 1939 Register also noted his birth

year as 1906. There were only three people in the household at the time, Sam, his mother and his

sister, Maggie, so it is likely that either Sam or his mother (or both) thought he had been born in 1906.

Like his younger sister, Maggie, he was not baptised despite there being a new church in the village,

which was within throwing distance. His older brothers Dick and Jack had been baptised together on

4 June 1904, so either the local curate was not now so interested in having his flock baptised, or it

was his parents who were disinterested. Sam was raised in Preston, living here until around 1947 and

even when he left, he returned each year for his annual holiday, which shows his attachment to the

village.

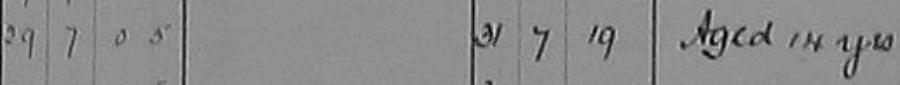

Preston School Register notes Sam being admitted to the school (Pupil No 633) on 4 August 1908

and leaving on 31 July 1919, the day after his fourteenth birthday:

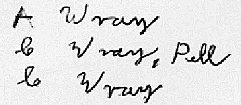

Sam appears not to have been interested in education. His writing was

poor (see right) and his spelling ability was challenged by words of more

than four letters. In later years, he struggled each week to complete the

work sheets of the gang of workers he controlled and it was painful to

see him write out betting slips - every letter was labouriously spelt out.

Yet I am convinced he had an agile mind. When enjoying card games or dominoes, he could remember

the sequence of cards that had been played and he never faltered when calculating the finish needed

for a darts victory. When he married my mother the ‘signatures’ of bride and groom and witnesses were

obviously written by one hand, probably my mother’s father (see later).

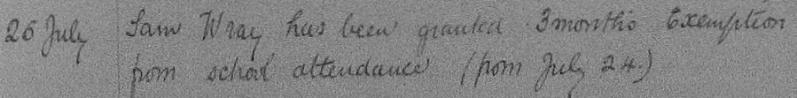

Perhaps a clue as to why he was so poorly educated is given by an entry in the School Log Book on

25 July 1918:

He was thirteen when he was given this special dispensation - and at a time when school attendance

was carefully regulated because of its impact on fees, it might seem that there were special

circumstances which were taken into consideration - not least that this was the hay-making season.

Sam was ‘taken under the wing’ of Ralston De Vins Pryor - quaintly known by the villagers as ‘RDV’ to

distinguish him from his brother ‘GIE’. My mother said that Sam was helped by a local squire who

taught him the rudiments of cards and billiards/snooker. To my surprise, in 2005, I discovered

confirmation of this relationship in my shed! I have an old woodworm-riddled fork that was used by

Sam which has ‘RdeVP’ etched into its handle.

The Pryors owned the Temple Dinsley Estate at Preston before moving to a house called, ‘The

Laburnums’ (now Pryor House) at Preston Green. RDV was a Preston school manager with an

interest in growing roses. The two Pryor brothers were also the driving force behind the village cricket

team after World War I.

I’ve been told some stories about Sam and RDV. Firstly, David Peters wrote, ‘The Laburnums had a

fine billiard room (across the courtyard from the house)….. I now remember that your father tended

the kitchen garden.’ Typical of several news reports is this from 1913, ‘In Class 1 for twelve distinct

roses the first prize was carried off by Mr R Pryor of Preston who had in his collection the best bloom

in the show - a very beautiful specimen of Yvonne Vacherot.’ I mention this because after he retired,

Dad tended the gardens of local residents and Mum and I would joke about his method of pruning

roses - which was to ‘cut ‘em hard to the ground’. It would now appear that he had a good teacher!

I was also told that when he was dying, RDV asked to see Sam, but his protective/jealous

housekeeper didn’t pass on the message.

The 1921 census revealed that Sam was working as a farm labourer for Joseph Priestley at Tatmore

Place, Gosmore. This was news to me! (For more information about Sir Joseph and Tatmore Place,

see Link: Sir Joseph Priestley)

Sam’s relationship with his parents is clear. He was close to his mother, who doted on him as her

youngest son and it suited him to stay at home and enjoy her ministrations. When she broke her hip,

he made a ‘Heath Robinson’ crutch from a broom which she used constantly - she was known as

‘Grannie with the broom’. But he heartily disliked his father. ‘Not a nice man’, was his stark, bitter

comment. One can feel a lightening of the atmosphere at Chequers Cottages when Alfred died in

1934.

Sam was also very close to and protective of his younger sister, Maggie. They were partners playing

darts and tended the local tennis court together. He got on well with Maggie’s husband, Ron Whitby.

They shared an interest in cricket and poached together. Ron would check whether the local

gamekeeper, Frank Harper, was in ‘The Red Lion’ and, if so, the two would poach rabbits and sell

their haul in ‘The Bull’ at Gosmore. Ron was to be Sam’s best man. Even today, local folk tell me that

Sam was a poacher. He would often recount stories of his poaching when he would outwit the police

constable and the gamekeepers. On one occasion, he was hunting with two ferrets which were put

down different rabbit-holes. The two groups of fleeing rabbits met head-on in the burrow and Sam lost

his ferrets.

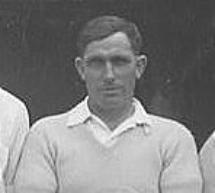

Sam in the 1920s

In August 1932, Sam was involved in a minor traffic accident:

‘Doctor Motorist Fined: Doctor Robert Colson Williams of St Davids, Moreton Avenue,

Harpenden was fined £3 for driving motor car without due care and attention at Gosmore,

near Hitchin on June 16. The defendant pleaded not guilty. Evidence was given by Mr Fred

Andrews of The Chequers, Preston who was cycling towards Preston from Hitchin in

company with Mr Sam Wray of Preston after a visit to Purwell Greyhound racing track.

Mr Andrews stated that a car driven by the defendant shot out in front of them at the Gosmore

crossroads and both he and Wray collided with it. Witness heard no hooter or warning of any

description. Mr John Payne. gardener, employed at Tatmore Place who was chatting with the

licensee of The Bull public house at the time of the accident which he witnessed also gave

evidence for the prosecution. Mr Ottaway for the the defence submitted that his client did not

dash onto the crossroads at a speed of 20 mph as had been estimated by a witness. His

client’s car was only lightly scratched which showed it was only a slight collision. Dr Williams

and his fiancee, Miss Edna Claridge (who was a passenger at the time) gave evidence. Miss

Claridge stated that Dr Williams could have done nothing to avoid the collision. The Chairman

in announcing the magistrates decision said that although the defendant had shown some

caution, he had not taken sufficient precaution in view of the dangerous nature of the

crossroads.’

View of crossroads travelling from Hitchin

Even after leaving Preston, Sam regularly went to Greyhound races at Portsmouth, enjoying the

experience and especially the betting. He (aged, 27) and Andrews (a forty-four-year-old gardener)

cycled a round trip of around eight miles to the Purwell track.

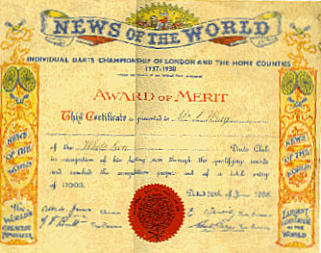

Returning to Sam’s work, at some stage he was labouring for Mr Maybrick at Preston Hill Farm - when

married, in 1946, he and Mum lived near the farm in one of its associated cottages. However, maybe

he also worked at Castle Farm - the photograph below portrays him in his familiar slouch with Reg

Darton of Castle farm, who ‘won prizes for ploughing each year since 1948’. I was told that this image

was taken ca.WW2 - in 1939, Reg was living with his patents in one of the Jacks Hill cottages and

although a game-keeper there is a note: ‘at present tractor driving’.

Sam in around 1942. Although I am speculating here, Mum first went to Preston in January 1941.

remembering this is in wartime, perhaps this photograph (clearly a studio shot) was one she sent

to her parents of the man with whom she had a relationship.

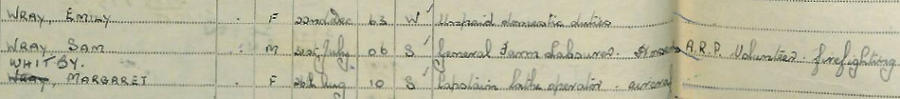

Since we have arrived at 1939, below is the entry for Sam in the Register of that year. He was living

at 5 Chequers Cottages with his mother and sister, Maggie, working as a general farm labourer

(horses) and was an air raid warden with fire-fighting duties:

Summarizing his life to date, Sam’s formulative years can be simply summed up - he worked for local

Preston farmers, developed a thirst for beer and a talent for cricket, football, billiards/snooker, cards,

dominoes and darts (to which we will return).

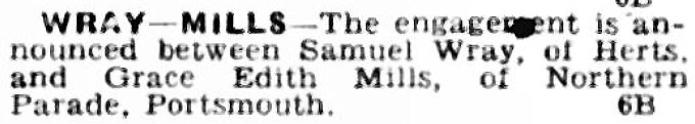

Then, on 28 September 1943, the Portsmouth Evening News carried this announcement:

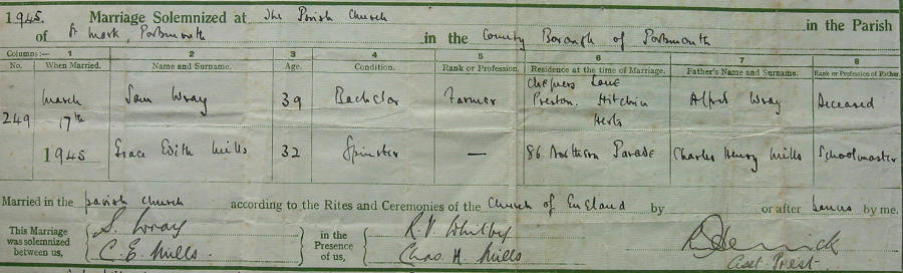

There is an undertone here. His middle-class, future in-laws (who doubtless placed the piece) gave

his name as Samuel. The wedding duly took place on 17 March 1945 at St Marks, North End,

Portsmouth - but that undertone was still lurking - Sam was a ‘farmer’ (certainly not the first time and

ag lab’s status had been elevated) and, curiously, the ‘signatures’ were all written by Grace’s father,

Charles Mills in maybe a smoke screen to deflect attention from Sam’s writing capability.

It seems to have been a low-key wedding. There is only one extant wedding photograph, in which

Sam seems stiff and ill at ease. He was probably conscious of the difference between his social

standing and that of his bride’s family. His best man was his brother-in-law, Ron Whitby.

Grace is not wearing a wedding dress in the photograph - rather an expensive ‘two-piece’. She was

to wear this for later photographs with her young children. We should remember that this was after six

years of world war. Austerity was the new vogue.

I don’t know who attended the wedding. Her father was present - and signed the certificate as a

witness. Were Sam’s mother and Grace’s grandmother able to travel? Grace’s brother did not attend -

possibly because of his RAF commitments. Grace commented later, ‘Mum and Dad were very much

against my marrying Sam, of course’. Bearing in mind that she was thirty-three, distinctly on the shelf

and now profoundly deaf, perhaps there was an element of desperation in her decision. Sam was

almost forty years old and unalterably fixed in his countryman ways.

More than sixty years later, I heard several similar comments from Sam’s family and Preston villagers

about the suitability of the marriage. One said, “(Grace) was a lady”. Another, “(Preston village was)

not the right place for her...you’ve got no business taking her there”. The consensus on both sides

was that there was a social chasm between the couple.

Yet the partnership endured. More than fifty years later, the couple were still together. In their

respective universes, both were well known and popular people. It was impossible to walk down the

street without their being stopped by someone who was within their orbit - it was just that they seldom

walked together.

The couple made their home in a farm workers cottage, Reeve’s Cottage (below), at Preston. The

cottage was probably the oldest home in the village with exposed wooden framework, low ceilings

and rather cramped - or so it appeared to me when the modern-day owner showed me around.

Without actually knowing, but rather imagining her feelings, although Grace was familiar with Preston

and knew some of the local folk, village-life after living in Portsmouth and then London must have

been hard to which to adapt. The cottage was isolated, being almost a quarter of a mile from

neighbouring homes. There was one shop in the village. The nearest town was three miles and a

bus-ride away. Her husband’s family were country people and his two sisters who lived locally had

personalities which wouldn’t have drawn Grace into the bosom of their family. Probably, she threw

herself into caring for her home and husband and found relative normality in the local country church.

But it’s likely that Grace struggled to come to terms with her new life. She loathed Preston and

refused to return in later years.

Married life in Preston, Hertfordshire

Reeves Cottage in 1977 (left) and 2020. It appears neat and cared for - with its carefully tended

lawn and flower bed. I’ve seen a photograph of the exterior of the cottage a short time after

Grace and Sam lived there and it looked like a typical farm labourer’s home - a little run-down,

unkempt and small (without the extensions which have obviously been added since).

I now attempt to reconstruct Sam and Grace’s movements immediately after their marriage from

available evidence (including photographs):

April 1945 - living at Hill Farm Cottage, Preston

January 1946 - son born at Southsea, Hants. Following this, Grace stays at Portsmouth for several

months while Sam lives at Preston. He is in the team cricket photograph from the summer of 1947.

Grace and son join Sam at Preston sometime before Xmas 1947. (I have a definite memory of being in

the village when a toddler). Sam played cricket for Preston on 22 May 1948

October 1948 - Grace’s mother dies at Portsmouth.

April 1949 - daughter born at Portsmouth.

Sam joins Grace and his two children at Portsmouth probably soon after April 1949.

Summer of 1949, Sam and Grace take son and new baby to Preston to show daughter to his family.

Son and daughter at Portsmouth, Xmas 1949.

Sam was definitely at Portsmouth before the summer of 1950. Grace’s brother recalls an almighty row

when the family arrived at Portsmouth

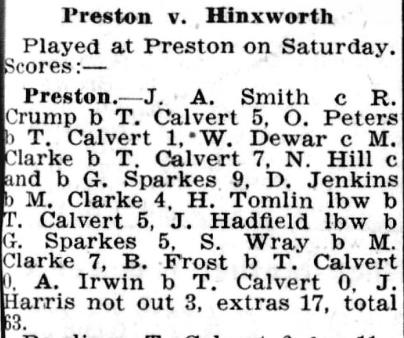

But there is a red herring as Sam played cricket at Preston on 18 August 1950 (see the following

scorecard):

So was Sam living in Preston at the time?

The clue to the circumstances of this report is the date, which is around the time he habitually took

his annual holiday and travelled back to Preston to help get in the vegetables and shoot a few

rabbits.

The move to Portsmouth was almost inevitable. Grace’s mother had died. Her father needed support.

There was room at her father’s house for Sam and Grace’s young family. So, after forty-four years in

a small rural community, Sam was pitched into life in a big city. In fairness, he seemed to adjust well -

particularly because he excelled at sports and pastimes, which were his entree to the local social

scene.

He found a labouring job with the Portsmouth Gas Board and rose to the dizzy heights of being a

‘ganger’ - which simply meant that he was in charge of a small group of men who caused traffic chaos

by digging up roads and tinkering with the gas mains. He would have a small breakfast in the kitchen,

drinking hot tea from a saucer and then be picked up by a lorry and taken to his latest assignment.

Sam also took up a new sport - bowls. Grace’s father was a keen bowler, organising major bowls

events at Portsmouth which attracted a large number of competitors and for which he received many

plaudits. Just across the road from where the family lived were two bowling clubs. Whether it was due

to his father-in-law’s encouragement, or male bonding or simply to score points over his father-in-law,

Sam quickly settled into a winning habit (note the mentions of Chas. Mills, Sam’s father-in-law):

Sam and Grace settle at Portsmouth

1953

1957

Ophir Bowling Club, Northern Parade, Portsmouth

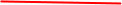

Sam was a renowned darts player - his skill being honed

while playing by paraffin light at Preston’s Red Lion. In 1938,

when playing for the White Lion, Hitchin, he won the local

area’s competition for the famous News of the World trophy

which had more than 17,000 entrants. He received a

‘cerstificate’ (right) for this which was one of the few pieces of

ephemera that he kept.

At Portsmouth, he played initially for the The Avenue, which

was just down the road from his new home. In September

1952, he was mentioned in the weekly dispatches:

It wasn’t long before Sam joined a ‘crack’ darts team at the small pub Wingfield Arms, Lake Road,

Portsmouth. In 1957, after 27 matches, they were second in their league and three of their players

were in the top four, having only lost five of twenty-seven games:

The victorious Wingfield Arms dart team with Sam, Billy Beasant (A) and Frank Crumlin (B)

A

B

When playing darts, Sam revelled in being in the limelight

and winning. He would slouch at the oche with one foot

against the bar and look sideways (with one eye narrowed) at

the board through a haze of cigarette smoke from the 98%

‘rollie’ he was smoking and lob the dart at the board. He

wasn’t using new age tungsten darts - the barrell was made

of brass with a point soldered in, the shaft was shaped from a

dowel and the flights were bought as cardboard cut-outs

which were glued on one side and stuck together and then

slotted into slits at the top of the shaft. In truth, Sam could

throw anything that even remotely resembled a dart. At one

Gas Board Sports Day, I remember him at a darts stall

winning box after box after box of chocolates until being told

to go away, he was too good. I saw him when he represented

Portsmouth in a darts match against Gosport when he

nonchalantly threw 180. At the age of sixty, he was Darts

Champion of Portsmouth (see right)

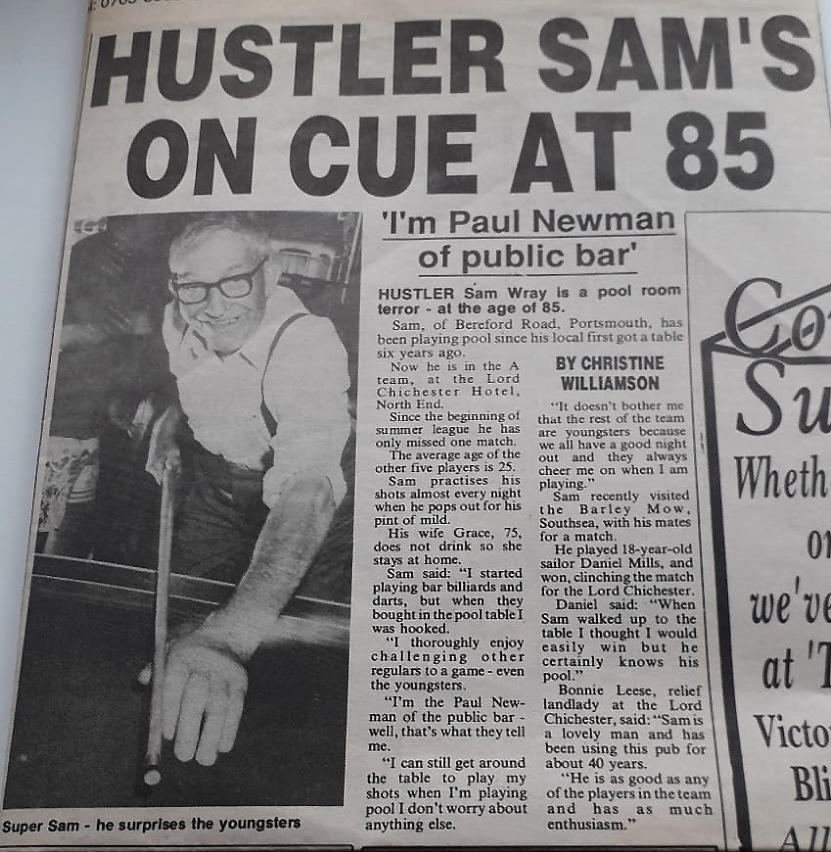

In the early 1960s, a pub game called bar billiards became popular

and local leagues were created. This was superseded by pool, to

which Sam took like a duck to water. He was in nine-ball heaven. It

was another opportunity to show his talents in public and to savour a

pint at the same time. He delighted in playing flash, young dudes. He

would shuffle around the table, very slowly, until they became

extremely frustrated and then came the canny positional plays and

the game was in the bag.

The local paper ran an article which featured Sam. It had the caption,

‘They call me the Paul Newman of the Pool Table’. The irony being

that I’m sure Sam didn’t have the slightest idea as to who Paul

Newman was!

But of all his sporting activities, it was cricket that was closest to Sam’s heart and the one about which

he reminisced the most - for ‘out of the heart’s abundance the mouth speaks’.

Sam had excellent hand-to-eye co-ordination. He wallowed in performing on a big stage when he

was supremely confident in his ability not only to throw accurate darts but also to do the quick

arithmetic needed to calculate his finishes without interrupting his play. I saw a countryman’s cunning

in his approach to darts and he was at his best when money was on the table for the winner. He was

painstaking in his approach to darts. He would only sup his “mild” from a tankard with a handle

because “straight” glasses might be tacky from spilt beer and this could make his fingers sticky which

might affect his grip when throwing.

He followed in the footsteps of his older cricketing brothers, Arthur, Frank and Bob, and apart from a

brief flirt with the Kings Walden team in 1929, he played for Preston from 1921 (aged 16) until he left

the village in the late 1940s, last playing for the team in 1950.

Sam was included in the ‘Preston All-Time Best XI’ - an accolade indeed! He regularly took 100

wickets in a season (when the team only played on Saturdays). As the photographs below illustrate,

he was (strangely) a left-handed batsman and a right-handed, slow, (again, strangely!) opening

bowler.

He regularly took a huge haul of wickets – 1930: 6 wickets for 26 runs, 1931: 6 for 18 and 5 for 7,

1948: 4 for 16 and 5 for 28. In 1924, a newspaper reported that ‘the Wray brothers (Frank and Sam)

were as usual on the wicket’ after taking four wickets apiece for less than ten runs. In the 1926

season, ‘the Wray brothers destroyed side after side’ and in the mid-twenties Sam was described as,

‘a brilliant youngster’.

Maybe the Preston pitch was a contributing factor towards Sam’s early performances. It was a

reclaimed meadow and was ‘a plantain patterned table’ - which implies that the playing surface was

affected by large-leaved weeds for several seasons! In 1928, it was said that the Preston wicket must

have improved because scores became higher.

Perhaps Sam was motivated by a desire to ‘get one over’ on the opposing batsmen. He often

delighted in telling us how one luckless cricketer made his exit to the pavilion muttering, ‘You cunning

little bugger!’ I replicated this scenario in 1962 when he told me to take my ‘whites and boots’ before a

holiday at Preston. I was playing for my school’s first XI (despite being younger than the rest of the

team). It transpired that he had arranged for me to play for Preston - the last time a Wray graced the

Preston wicket. I opened the bowling and took a wicket in my first over - the batsman, cursed me

saying I was a cunning little *******. Sam was so proud, not for my taking the wicket, but the manner in

which it happened.

Sam at the cradle of cricket,

Hambledon, Hants

Sam the man

When working, he had a simple daily routine. He got up at around

seven o’clock in the morning and had a hurried breakfast when he

drank hot tea from a saucer. Sam was collected by a lorry to go to

work and brought home just after five when he had his meal and a

‘snooze’ to recharge his batteries. I might get some attention for a

short time before he shaved and left for the pub at about eight

o’clock. He would return after closing time, have a small supper

and then to bed. Sundays had their own timetable which involved

a fried breakfast, a lazy morning, going to the pub at lunchtime,

‘sleeping it off’ in the afternoon and back to the pub in the evening.

As well as the sports and pastimes mentioned earlier, he went to

greyhound racing events at Tipnor, Portsmouth and also enjoyed

watching wrestling bouts and attended occasional football

matches at Fratton Park where Pompey were playing.

Then, came retirement and Sam became ‘a potterer’. His local pub, ‘The Pelham Arms’, was

refurbished, and he built a greenhouse from rescued wood and glass. He ran electricity to his palace

and there he spent much of his day pottering and smoking. He did some paid gardening work for

widows in the neighbourhood and then in the afternoons there was horse racing on television and in

the evenings there was the pub.

Money wasn’t a problem. He had a small injury pension after an accident at work that affected the

tendons in his right hand. Sam had few, simple pleasures and there always seemed to be enough for

his beer, his cigarettes (hand rolled St Julian Empire tobacco in blue Rizla cigarette paper) and his

bets which were usually of the five pence double and cross accumulator variety. How the bookies

must have valued his custom! He had a small booklet which had tables of what was won at different

odds - and seemed to be able to work out exactly what he was owed, which is complicated when the

bet is an accumulator.

Sam took his annual fortnight holiday at the end of August when he returned to Preston, sometimes

with his children. There he would enjoy digging up and storing the household’s vegetables. He would

watch the harvest being taken in and shoot fleeing rabbits. The evenings would be spent in ‘The Red

Lion’ or perhaps his nephew’s husband, Freddie Angel, and Cyril Varral would drive over from Luton

and take him to another pub. At the weekend there was always cricket and the opportunity to

reminisce with old friends. He would also visit some of his relations like his sister, Maggie, his

brother, Dick and Phyll and Herbie Jenkins at Castle Farm. Sometimes his holiday would coincide

with visits by his brother, Jack.

Then, it was home with his spoils. A few freshly killed rabbits in a sack. I can still recall their smell

when I excitedly woke the morning after Dad’s return and opened the pantry door to see the sack on

the floor. Mum would be expected to prepare and cook them - which she must have hated. I find it

astonishing that Sam travelled by two trains, with a taxi jump across London, carrying dead rabbits.

These holidays ended in 1978, when his sister, Nan, died and the cottage was sold - the end of an

era for Sam. I drove him to Preston in 1977 when the photo below was taken:

Sam at Preston with (l to r): Mr Stanley, Percy Sharp, Dickie Jenkins (a cousin)

and Sam’s brother, Jack Wray.

Sam was popular with the outside world. He would be the life and soul of the

bar, showing his public face. To walk down the street with him was to be

constantly stopped for a chat. He seemed to know everybody. Even when we

sold the family house the estate agent remembered Sam and how he and his

friends tried to trick him when they were young - but Sam was equal to the

challenge.

He liked something for nothing which is probably why gambling was so

appealing. Being a natural niggard controlled the amounts he bet. When he

was walking, he constantly scoured the ground for lost coins and when he

found one - what joy!

He enjoyed more than his fair slice of good fortune. Time and again he would

gleefully bring home a prize won in a raffle. When he played cards, invariably

the right card for him would be dealt. He found his best darts at the critical

time. When playing pool, the ball would run on just that extra inch to improve

his position. It was maddening and uncanny for ordinary mortals. There

comes a point when skill replaces good fortune.

His inflexible attitude to clothes marked him as a country man.

He invariably wore a cap and cardigan. He favoured black

boots of a particular type and tweed jackets. The only

changes to his wardrobe were to replace items with new,

identical garments.

Sam’s rural heritage was also shown by his taste in food. He

loved brawn, chitterlings, pig’s trotters, salt beef and chicken’s

giblets. He also had an uncanny knack of keeping dry from

the rain. As he walked, he would deliberately seek the lee of

walls and used trees for cover. He also had a strange habit of

filing his nails using the bricks of a wall – which I associated

with his countryside background.

Beer flowed through Sam’s life - in the farmer’s fields and his

local pubs. On special occasions, like birthdays, he liked

‘shorts’ such as rum and blackcurrant. Yet, despite his love of

alcohol, I never saw him obviously the worst for drink or hung

over. His normal evening’s consumption would be three or

four pints. He drank mild with a lemonade ‘top’ in later years.

He had a healthy constitution no doubt reinforced fresh air and exercise. He had a bad bout of

pneumonia in the early fifties. He walked with a limp following a kick on the ankle while playing

football. He often suffered with painful cramp when in bed. In the seventies, after years of discomfort,

both hips were successfully replaced. He used two sticks after his operations. Later in life, he was

diagnosed as having an under-active thyroid gland. One of the effects of this can be a feeling of

lethargy and fatigue.

In December 1994, Sam had a small stroke. Then, on the fourteenth, at around nine o’clock in the

morning, Mum took him a cup of tea in bed. He pulled up his bedclothes, gave a little sigh and that

was that.

Postscript