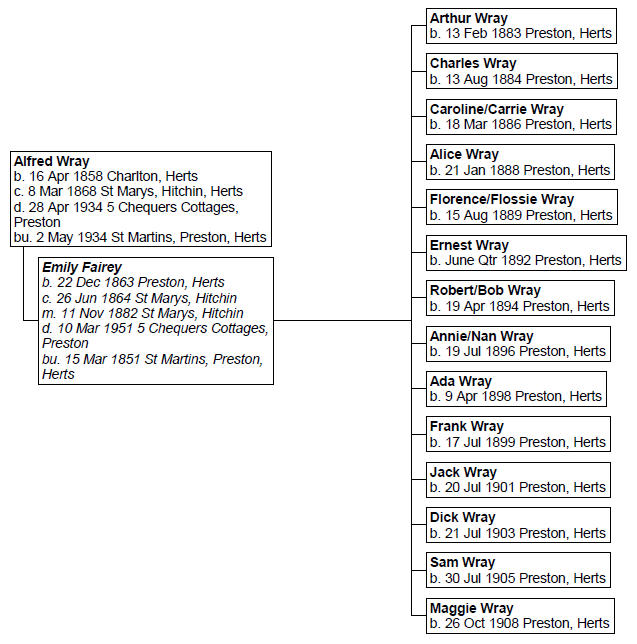

Grandparents: Alfred and Emily (nee Fairey) Wray

I didn’t know my grandfather, Alfred Wray. I remember asking my father what he was like.

Dad had drunk a couple of pints of mild but these hadn’t loosened his tongue. He didn’t

want to talk about him, ‘He wasn’t a nice man’, he said - end of conversation!

But I do remember my grandmother, Emily. As a young child I lived in Preston and later

spent summer holidays at her home when she was alive. I have an impression of an old

lady, dressed in black, sitting in a chair in the living room.

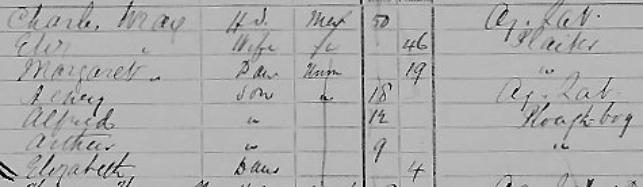

Alfred Wray was born on 16 April 1858 in Charlton, near Hitchin, the fourth child of Charles and

Elizabeth Wray. The Wray family was living at Austage End which is less than a mile from Preston.

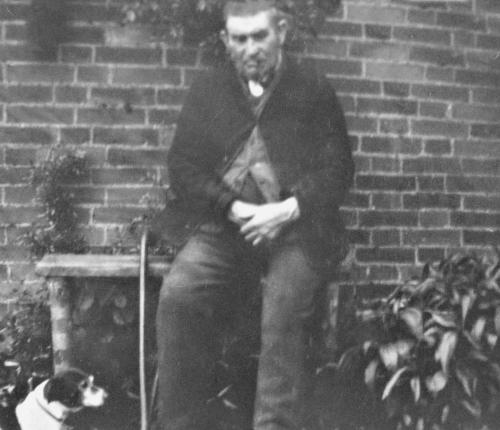

Ten years later, Alfred was baptised on 8 March 1868 in the parish church of Kings Walden as part of

a batch of births with his brother and sister, Arthur and Elizabeth Jane. He was noted as being ten

years old.

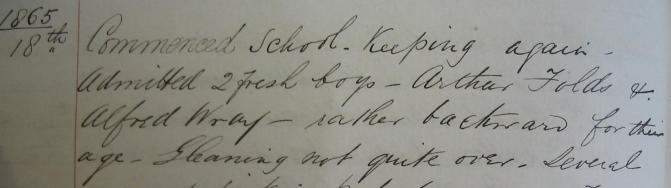

Alfred was admitted to Breachwood Green School, Kings

Walden (shown right) in the late summer of 1865 when

he was aged around seven years.

This probably explains the comment in the school log

book that he and another boy were ‘rather backward (in

an educated sense) for their age’

When the 1871 census was taken, the Wray family was still living at Austage End and Alfred and his

younger brother, Arthur, were working as plough boys. Arthur was reported to be nine years old which

suggested that Alfred was also working at that age. Perhaps he was educated for only around two

years.

St Marys, Kings Walden, Herts

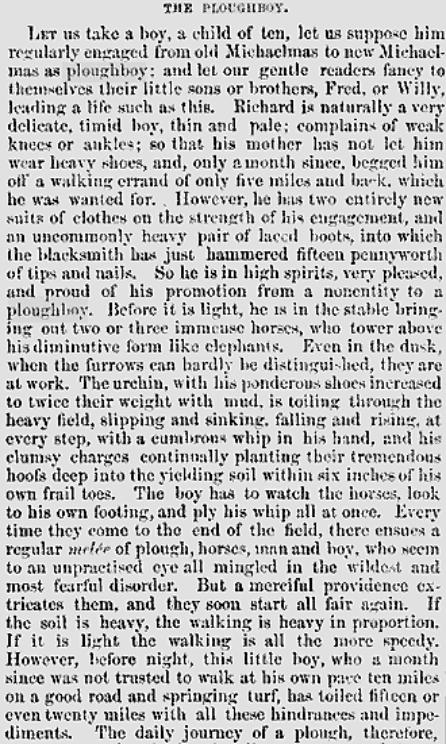

The plough boy’s day started early as the

horses had to be readied for work and fed

before 7.30 am. He would work until 4 pm with

two short breaks and would plough about three

quarters of an acre. When he got back to the

farm it was time for dinner and then he

unharnessed and settled the horses down for

the night. Finally, he would trudge wearily

home arriving about 7.30 pm. When he went

to bed, he would sleep ‘pretty firm’.

In 1886, a farmer bemoaned the introduction

of schools because he now had to pay plough

boys 5/- a week, whereas before it was 2/6d.

It was common for a boy to work as a plough boy on leaving school. It was leg-aching work, trudging

beside or behind horses and doing his best to keep them going - cracking his whip or talking

encouragingly. He had only ‘ a short stop to eat his bread and cheese,or bacon with a bottle of cold

tea.’ The plough boy was controlling the horse(s) and the plough and the clogging nature of the clay

and flint at Austage End must have made his work heavy.

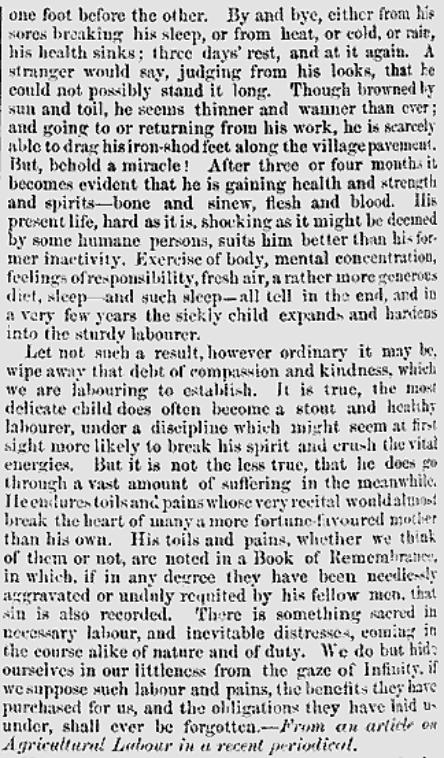

The following is extracted from Sharp’s London Magazine (1846):

Emily’s childhood

It wasn’t until 1939 that The Register revealed Emily’s birthday as 22 December 1863:

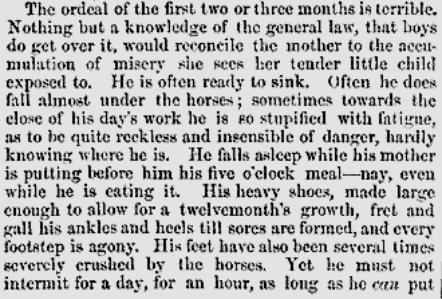

She was baptised on 26 June 1864 at St Marys, Hitchin as the illegitimate daughter of Mary Feary (sic):

For years I believed that Emily’s father was Thomas Currell - and she grew up in the household of

Thomas and Mary at Gosmore after they married on 2 November 1867. However, a chance sighting of

a newspaper report of an affiliation order awarded in favour of Mary disclosed that Emily’s father was in

fact the agricultural labourer, William Cox.

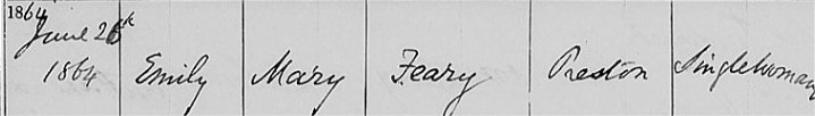

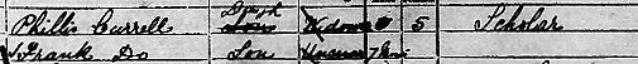

By 1881, the Currell’s had moved to Back Lane in the village of Preston and the Wray’s were still living

at Austage End. Emily was a straw plaiter:

In March 1882, both Emily and Alfred were involved in a court case. The newspaper report of the

case gives an insight into their lives. Emily was employed at The Bull inn, Gosmore:

C

harge of Receiving Stolen Property near Hitchin.

Thomas Jeeves, aged 30, publican, of Gosmore, near Hitchin, and Ann Jeeves, aged 28, his wife (both on

bail) were indicted for receiving two bushels of maize, value 10s., the property of Mr. Charles Cholmeley

Hale of Kings Walden, well knowing it to have been stolen, on the 2nd of March.

Mr. Fulton and Mr. Wedderburn prosecuted; and Mr. Woollett and Mr. Holland defended the prisoners.

The case occupied a very long time, but although a somewhat complicated one, the main facts are

comprised within a small compass. Mr. Hale, the prosecutor, lives at Kings Walden, and had in his employ

a carter named Matthew Reeves. On the 25th February, Reeves was instructed to fetch a quarter of maize

from Messrs. Franklin’s of Hitchin, being furnished with a written order for that purpose. For some reason

which did not transpire, Reeves either did not fetch the maize upon that day, or did not take the whole of it;

but upon the 2nd of March he was sent with an empty cart to Hitchin to fetch three quarters of oats from

Messrs Franklin’s, and he then received, in addition to the oats, four bushels of maize, which at his

request were put into two sacks, one of them having Messrs. Franklin’s mark upon it, and the other one,

the mark of the Great Northern Railway Company. The prisoners live at Gosmore, on the road between

Kings Walden and Hitchin, where they keep the Bull Inn; and the principal witness in the case was

Matthew Reeves, the carter, who pleaded guilty before the magistrates to stealing the maize, and who

was now brought up in charge of a prison warder. He stated that on the morning of the 2nd March, while

going towards Hitchin with the empty cart, he called at the prisoners’ house about nine o’clock, and

Thomas Jeeves asked him if “he would get him a few maize that day”, and Reeves said he would try. He

then went on to Hitchin and received the oats and the maize, the latter at his request being put into two

sacks. On the way home he again called at the Bull, about eleven o’clock, and there saw Mrs. Jeeves,

whom he told he had brought her some maize, and she told him to put it behind the club-room door, where

he left the sack with Messrs. Franklin’s name upon it. Mrs. Jeeves gave him 3s 6d and a pint of beer,

which he, and a man called “Snip” and Mrs. Jeeves drank between them. He (Reeves) then continued his

journey to Preston, where William Jeeves keeps the Chequers public-house, and there he saw both

William and Thomas Jeeves. In cross examination, the witness said he had never been charged with

stealing before, and that he should not have been upon this occasion if he had not been bothered into it by

Thomas and William Jeeves.

Police-constable Day stated that about eleven o’clock on the morning in question he saw Matthew Reeves

take something heavy in a sack from his cart and carry it into the Bull Inn; and Superintendent Reynolds

stated that about four or five o’clock in the afternoon, in consequence of something he had heard, he went

to the Bull and asked Mrs. Jeeves if Reeves had left anything there that day, and she replied, “Not that I

am aware of”. On looking about, however, he saw the sack in the clubroom and saw that it contained

maize but at that time he had not heard of any maize being stolen. He returned to the house a couple of

hours later with Police constable Day and took possession of the sack, and directly after leaving he met

Thomas Jeeves on the road, and asked him if he had ordered any maize that day , and he replied, “No,

but I don’t know whether my wife has, as I have been away all day”. In cross examination, the witness said

that when he spoke to Mrs. Jeeves, she said (pointing to the sack), “If anything has been left, it must be

that, but I have been away at a funeral and left the house in charge of my little girl”.

William Stevens, who lives close to the Bull, stated that after Inspector Reynolds had left the house, Mrs.

Jeeves called him into the taproom and asked him if he wanted to earn a pint of beer. He replied, “Yes, he

should not mind,” and she told him to go to William Jeeves at Preston and tell her husband to come home

as quick as he could. George Reeves, a wood-dealer, brother to Matthew Reeves, stated that on Friday

morning, 3rd March, he saw William and Thomas Jeeves together. William said to him, “Your brother Matt

is locked up, “and on asking what for, he said, “About some maize, and ------- if me and my brother Tom

won’t be locked up too.” The prisoner Thomas said that, while going home the previous evening, he met

his wife’s sister on the road and that he had then returned to the Chequers to tell his brother to do away

with the maize (it was alleged that some had been left there also) so that the police should not find it.

Thomas Jeeves also said that he would not mind it costing him £20 or £30 if Matthew Reeves did not get

into trouble.

Samuel Reeves, another brother, and groom to Mr. Hale, stated that on the 4th March he had some

conversation with Thomas and William Jeeves about his brother Matthew’s case; and William said, “If the

stupid (meaning Reeves) had not brought me into it, I would have paid all expenses.” Witness said, “Well,

but what is he to do now?” and William said, “He can say he had a lot of beer, and lost it on the road.”

Witness then turned to Thomas Jeeves and asked how about the maize which had been left at his house;

and he replied that Matthew could say “he had left it there because the load was too heavy for the pony.”

Both the Jeeves’ said that they would give £10 or £20 if Matthew Reeves would keep them out of it. In

cross examination witness said both men said they would give £20 rather than have it occur at their

houses, but they also said what he had already stated, that they would give £10 or £20 if Matthew would

keep them out of it. Edward Roberts, Mr. Hales postman, was also examined for the prosecution, but he

appeared so stupid that little or nothing could be made out of what he stated.

This completed the case for the prosecution and Mr. Woollett for the defence said that he would prove that

Matthew Jeeves was not only a thief but a liar also. He contended that Reeves left the maize at the Bull in

the absence of Thomas Jeeves and his wife, intending to call for it later on, but finding him baulked, he

trumped up this accusation against the prisoners to shield himself. The following witnesses were then

called for the defence:-

George Bates, alias “Snip”, a tailor, who lodges at the Bull stated that he got downstairs soon after eight

o’clock on the morning of the 2nd March but that he did not see Thomas Jeeves all day, he having gone to

work before he got down. Matthew Reeves called at the house on the way to Hitchin, and spoke to the

witness about some tailoring he wanted done for himself and witness told him to buy the stuff in Hitchin.

Reeves did not see Jeeves at all as the latter was not there. On his way back from Hitchin, Reeves called

again and brought the stuff for the tailoring, but by this time Mrs. Jeeves had gone out and had left the

house in charge of Emily Currell. Reeves had some beer to drink, for which he paid himself and witness

helped him to drink it.

Emily Currell, a girl of nineteen, stated that she went to keep house for Mrs. Jeeves on the 2nd

March. She got there about ten o’clock in the morning and Mrs. Jeeves, who was going to a

funeral, left at half past ten. She did not see Thomas Jeeves all day. After Mrs. Jeeves had gone,

Reeves called saying he had a parcel to leave there and witness told him to put it in the club-room

and she would tell Mrs. Jeeves about it when she came home. Witness did not give him any money

but Reeves had a pint of beer for which he paid her a penny and two halfpennies, and “Snip” and a

man named Wray helped him to drink it. In cross examination witness said she told Inspector

Reynolds when he came to the house the same evening that she had received the sack and that

Mrs. Jeeves was not at home when it was brought. She was present before the magistrates, but

was not called to state what she knew about the case. (This was explained by its being stated that

the magisterial examination occupied a very long time and the magistrates having intimated their

intention of committing the prisoners for trial, the solicitor for the accused reserved their defence.)

Alfred Wray, a hurdle maker, who had gone to the Bull to get his lunch, corroborated the last witness

as to Mrs. Jeeves not being present when Reeves called. James Palmer and Joseph Peters, both of

whom work for Capt. Darton of Preston stated that Thomas Jeeves was also working for him on the 2nd

March and that they saw him at work on the premises at nine o’clock in the morning.

Capt. Darton stated that Jeeves had worked for him for about two years and he spoke to him in his

orchard at half-past nine on the morning in question. Witness saw what work Jeeves had done before he

spoke to him and he should say he must have been at work quite half-an-hour before. Jeeves lived two

miles from witnesses’ house. Witness had known him all his life and had always found him to be a

respectable, honest man. The witness then said he should like to know whether a convicted prisoner was

allowed to talk to the witnesses concerned in the case. He, together with the rest of the witnesses, had

been waiting out of Court since the case had commenced and he had noticed Matthew Reeves talking to

his brother Joseph Reeves (who was concerned in the next case) and whispering in his ear so quietly that

no one could hear what he was saying. It had nothing to do with the present case but witness thought he

would mention it as he liked to see the rights and the wrongs of the case. The Chairman: Thank you

very much.

Martha Chalkley, sister to the female prisoner, stated that the latter was with her from twenty minutes to

eleven until half-past four on the 2nd March and that during that time they went to a funeral together.

This closed the evidence for the defence and Inspector Reynolds and Police-constable were recalled by

the prosecution to contradict Currell’s statement that she told them she received the maize and

that Mrs. Jeeves was out when Reeves brought it. Mr. Reynolds said he saw her at the house the

third time he went there, between eight and nine o’clock and he believed she said something but

he did not know what it was because two or three people were talking together at the time. The

constable, being otherwise occupied, said he did not pay any attention to what was said.

The chairman, in summing up, said the jury would agree with him that it was a very strange story and that

on one side or the other there had been portentous perjury. But even if they believed the story for the

prosecution to be true, it would be their duty to acquit the female prisoner; because he thought they must

take it that she was under what the law recognised as the influence of her husband. Alluding to the

evidence of the principal witnesses for the defence, he said he saw no reason to distrust it; but, on the

other hand, the jury must remember that Matthew Reeves, the chief witness for the prosecution, was

under conviction at the present time and that when he first made his statement he had the strongest

possible reason for assisting the prosecution. The jury after three of four minutes deliberation returned a

verdict of not guilty against both prisoners.

The verdict was received with some slight attempt at applause which was at once suppressed.

The accused were then discharged. William Jeeves, aged 38, landlord of the Chequers Inn at Preston was

then indicted for receiving the remaining two bushels of maize (that in the sack belonging to the Great

Northern Railway Company) belonging to Mr. C. C. Hale; but after the verdict given in the former case, no

evidence was offered for the prosecution and a verdict of not guilty was returned by the jury

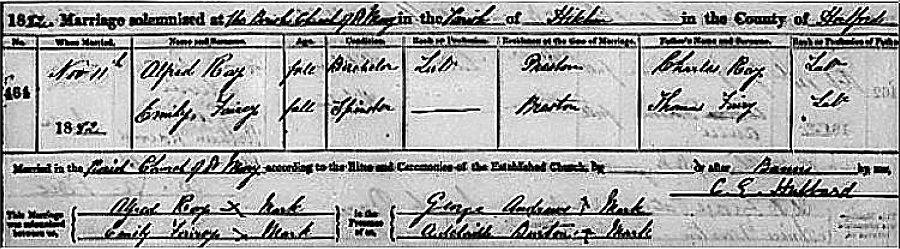

The marriage of Alfred and Emily

Nineteen months after the court case, Alfred and Emily married at St Mary’s Church, Hitchin on

11 November 1882. Unsurprisingly, both marked the register. Their witnesses were George Andrews

(Emily’s first cousin) and Adelaide Burton - who were later to marry and live at Preston Green.

The first of Alfred and Emily’s fourteen children, Arthur, was born a few months later in 1883. The

children were all healthy - ‘all born and lived well’. In 1891, Alfred and Emily and five children lived in

a two-roomed house at Back Lane, next door to Emily’s mother, Mary. Their home was immediately

to the north of the footpath which still leads to The Green. They had moved to Poynders Green briefly

in 1897 but by 1898 they had returned to Back Lane and were paying 4/5d (22p) rent a week to their

landlord, Mr. G.I.E. Pryor. Three years later, in 1901, the family had moved to the north side of

Chequers Lane. In 1911, they were again at Back Lane .Sometime after 21 April 1915, they moved to

5 Chequers Cottages, Chequers Lane, which had been newly built by Mr. Vickers who now owned

the estate at Temple Dinsley.

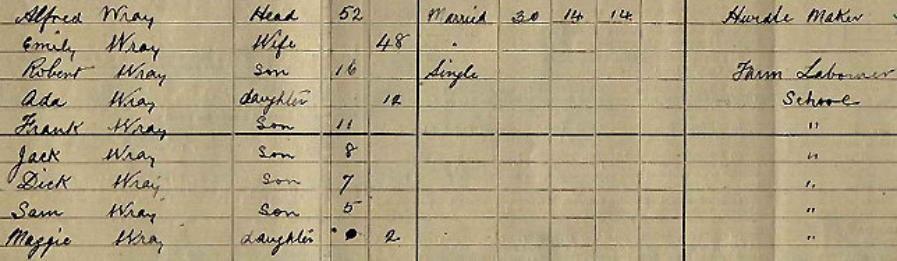

The 1911 census. The nine Wrays are at Back Lane Preston, shoe-horned into four rooms

Early photographs of front and rear elevations of 5 Chequers Cottages, Chequers Lane, Preston

The last of the children, Maggie, had been born in August, 1908. Their new (and final) home had the

luxury of three bedrooms, a kitchen and a long garden which provided the family’s vegetables and

where the chickens were kept.

At the rear of the house was a large barn with a high ceiling. It had an earthy, pungent smell.

Attached to the barn was a water pump which was fed by two underground tanks that collected

rainwater. Alfred and Emily kept chickens and bantams in the garden and a pig on land opposite their

home. The family’s diet was supplemented by the rabbits and pheasants which were poached by the

boys. For more details about Chequers Cottages see this link: Chequers Cottages

Alfred and Emily’s attitude towards the education of their children

Emily’s attitude towards her children’s education seems to have varied according to the

circumstances and needs of the family.

For example, her eleven-year-old daughter, Carrie, was ‘kept at home to plait’ and left school early

(aged 12) to ‘help her mother’. Similarly, another daughter, Alice, when eleven, was ‘frequently kept at

home to mind babies and was backward in consequence’ - at the time there were three children aged

three and under in the household. The children were dispatched to school as soon as possible - it

was a supervised haven and gave Emily time and space for her work at home.

Of the boys, Ernest Wray left school aged twelve to go to work. But his writing was far better than my

father’s scrawl. Dad’s spelling was poor - he struggled to write out his betting slips and trying to figure

out his winnings was a painful (if sometimes rewarding) struggle. Yet, Jack Wray received a watch for

five years perfect attendance.

In February, 1891 all the Ray (sic) children were sent home for their ‘school pence’ as six weeks

‘pence was owed – a sign of either their parents’ poverty or indifference to education.

Alfred loses a leg

It was only after the publication of the 1921 census that it has been possible to pin-point when Alfred’s

leg was amputated. This is a transcription of that census:

“Total disablement” probably points to Alfred being unable to work

because of his injury which clearly happened before 19 June 1921 when

the census was taken.

It may have been happened around the start of 1920 as the Preston

School log-book has this entry: 7 February. HCC approved the

appointment of Mrs Wray as a cleaner at a monthly salary of £1.

Did Emily take on this work in an attempt to support her family because

Alfred was unable to work - and did this indicate that his leg was

amputated in around the beginning of 1920? On 15 November, ‘Mrs

Wray resigned as cleaner’.

For some years Alfred followed in his family’s tradition and worked as a hurdle-maker - “’e laid ‘edges

lovely”. He was self-employed and travelled from farm-to-farm. However, while working in the woods

of the Temple Dinsley estate, Alfred lost a leg. He had been felling trees using a block and tackle

when a pulley wound around his leg.

As a result of this horrific accident, the family was allowed to live rent-free in their cottage by Mr.

Vickers - which helped to ‘make ends meet’.

Alfred - the man and his final years

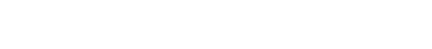

Alfred was not a tall man, but thickset. Based on the one clear photograph of

him I have, he appears morose and hard, almost cruel, with little evidence of

joyfulness. He has large hands which are a testament to years of hard manual

work. Of all his sons, it is said that his sons, Jack and Sam, most closely

resembled him.

According to many accounts Alfred was ‘not a nice man’ - ‘He was an old bu***r

who wasn’t nice to Granny.

Alfred was often bad-tempered and would threaten his children with his stick.

‘Do you want this across your shoulders?’. ‘I’ll fetch you one!’ His daughter,

Maggie, had to clean the hearth before he got up - or else. (‘But he’ll have to

ketch me first!’) When one of his grandsons misbehaved, Maggie sometimes

thought, ‘there’s a bit of Alfred in you’.

Although he ‘wasn’t a big drinker’, Alfred did smoke a pipe.

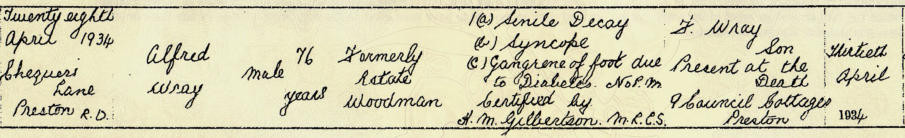

Alfred died on 28 April 1934 aged sixty-six. The causes of his death were

senile decay, syncope and gangrene of the foot due to diabetes. It is believed

that some dye from a sock infected his foot when he was tending a windmill at

the bottom of the garden. There was no post mortem.

The informant of his death was his son, Frank, who was living across the road

at 9 Council Cottages, Chequers Lane. Four days later, Alfred was buried in

the graveyard of St Martins Church, Preston.

1923

Of Emily Wray

Like many of the women in the village, Emily worked in service at Temple Dinsley. This environment

influenced the way in which she organized her own household. She ‘was very strict’ and ‘a stickler for

doing things properly’. Before every meal the children had to wash at the well.

My father had fond memories of ‘mother’ looking after him by bringing simple meals in a basin when

he worked in the fields. She is remembered for her meat puddings and pies.

Life was hard for Emily,with so many children for whom to care. She would regularly walk the three

miles to Hitchin on Tuesdays and Saturdays for the family’s shopping. The last haul up Preston Hill

burdened down with groceries must have been exhausting!

She also walked to Hitchin for the straw which she plaited and to sell the finished plait In the

summertime she might be found in the fields, often with her children, as she picked stones and

gleaned corn. She occasionally carried a bundle of straw home balanced on her head.

Emily had ‘some queer ways’. She was superstitious and insisted that knives and forks were

uncrossed when laid on the table. Her children were told ‘not to go up ‘Green Lane’ (Dead Woman’s

Lane?) as there were witches there’. The playing of tennis by the children was forbidden during the

times of church services and on Sundays there was no knitting or sewing of buttons as it was the

Sabbath.

Later in life, Emily ‘broke her hip and never had it fixed’. My father made her a crutch from an

upended broom which he padded for comfort. She was known affectionately as ‘granny with the

broom’.

Emily now was living with her children, Flossie, Nan and Sam for

company. In later years she wore a black dress, sometimes with a black

and white apron and sat in a rocking chair in the corner of the room. Her

hair was ‘scrunched back in a bun’. She would say ‘if you can see a

cobweb you can get up there and lick it down’.

On 10 March 1951, Emily died. She was eighty seven years old.

I remember when Dad received the telegram telling of his mother’s death.

It was early in the morning before he left for work. He was drinking tea

from a saucer. It was the first time I saw him cry.

She had suffered with diabetes (‘the sugar’) and she died from heart

failure and atherosclerosis which is a thickening of the arteries caused by

cholesterol plaque. Her daughter, Flossie Sugden, then residing at

Foxholes Maternity Home, Hitchin was the informant. Again, she

described Alfred as an estate woodman.

Emily certainly had a hard life bringing up so many children and with a husband who could be difficult.

From her photographs she appears worn but has a ready smile. She regularly enjoyed ‘her half of

stout at “The Chequers”’. A granddaughter remembered her fondly as a ‘real Granny…kindly, giving

and a good listener’.

Emily was buried five days later at St Martins Church, Preston. Her unmarked grave is near the door

of the church.