A History of Preston in Hertfordshire

Douglas Vickers and Temple Dinsley (1918 - 1929)

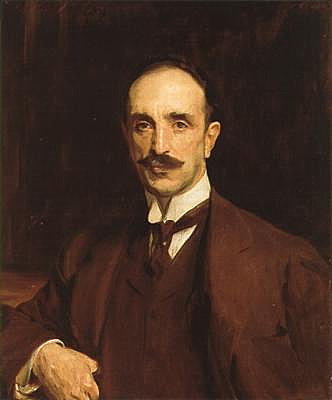

Douglas Vickers - painted by J S Sargent in 1914

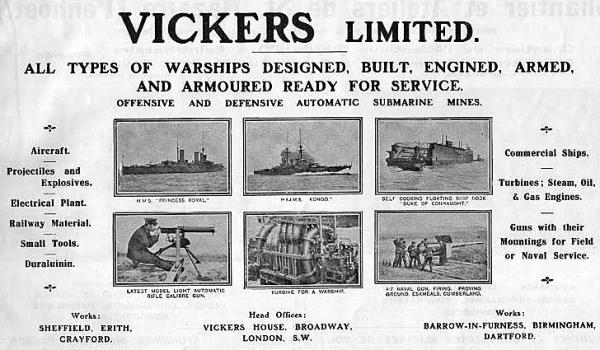

Even today, almost two centuries after the firm’s inception, Vickers is synonymous with heavy

engineering and armaments. After Douglas’ grandfather, Edward Vickers and his father-in-law,

George Naylor, had established a business in Sheffield, it was inherited by Edward’s two sons,

Thomas (Douglas’ father) and Albert Vickers.

After forging a name for steel castings - in particular, steel bells - the company branched into the

manufacture of ships’ shafts and propellers, armour plating, artillery, ships, tanks, torpedoes and cars.

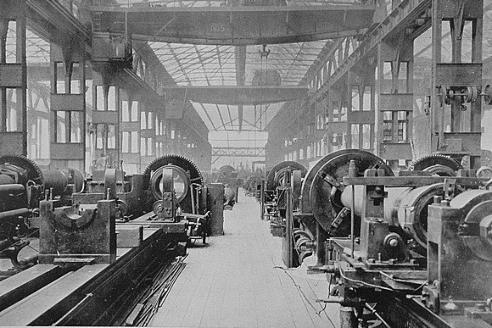

Vickers gun shop

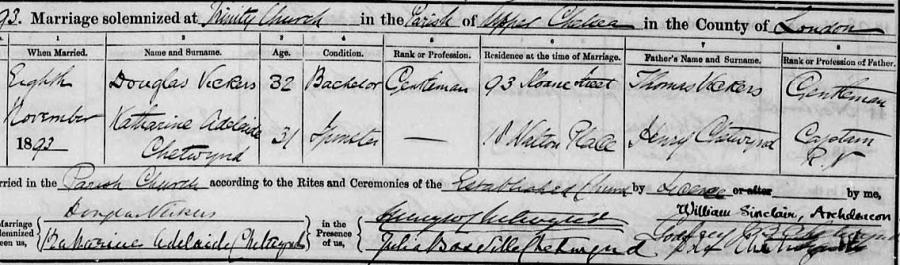

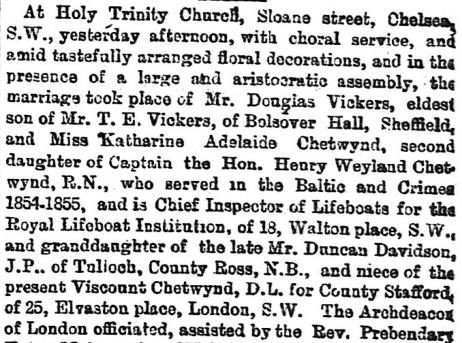

On 8 November 1893, Douglas married Katharine Adelaide Chetwynd:

Katherine’s mother was Julie Bosville nee Davidson - her grandfather was

Duncan Davidson, a London West India merchant and owner of Tulloch

Castle, Ross-shire. We will return to Tulloch Castle later (as did Douglas

and Katherine, often).

Penelope Douglas, has written a book, So Many Bridges, which draws on

her great aunt’s memoirs of the Vickers until 1918. Her comments help us to

understand a little of their lives and character at this time. She wrote that an

aunt recalled that Katherine had ‘married beneath her. She married trade!’

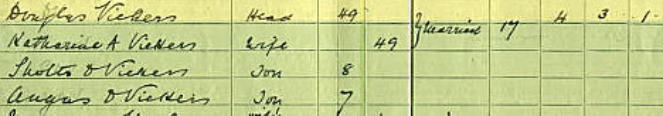

The couple had four children: Oliver Henry Douglas (1898–1928), Felicity

Ida Vickers (1901–1901); who died in infancy; Sholto Douglas Vickers

(1902–1939) and Angus Douglas Vickers (1904–1990) - the latter two are

pictured right.

In the census of 1911, the Vickers family are noted as being at Chapel

House, 19 Charles Street, near Berkeley Square, Mayfair, London (shown

right). The house had twenty-seven rooms on five storeys and a basement.

The family had an entourage of fourteen servants:

Douglas was appointed as a director of Vickers Ltd in 1897. Between then and the outbreak of WW1,

the company explored further branches of manufacture - The Wolseley Tool and Motor Car Company

and aircraft manufacture by the formation of Vickers Ltd (Aviation Department). A Vickers School of

Flying was opened at Brooklands, Surrey on 20 January 1912.

Douglas and Katherine Vickers - events leading to the purchase of Temple Dinsley in 1918

After briefly considering Douglas and Katherine’s background leading up to 1914, we will focus on

their situation in 1918, which may explain their decision to purchase Temple Dinsley - during a time

when a world war was raging.

The first factor is that Douglas harboured political aspirations. These were publicly broadcast in a

news item dated 1 January 1910 which remarked that he had ‘a keen ambition to represent that part

of Sheffield (ie Hallam) inhabited by his work people’. He stood for parliament in 1910, but was

defeated by an opponent who had an increased majority of 1,956. WW1 changed the political

landscape. The Conservative Party became more popular and Vickers’ workforce in 1915 was

197,000 (which included 23,000 women and girls). In the event of a post-war election, Douglas might

be confident of winning a seat in government - which was what happened in December 1918 when he

was returned unopposed. With this in mind, might a quiet country seat such as Temple Dinsley, only

thirty miles from London, be an attractive place to entertain his political circle?

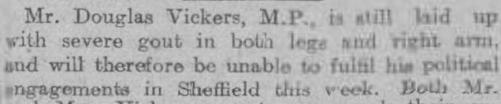

Secondly, Douglas’ health was becoming an issue. He was afflicted by rheumatism and gout, which

were exacerbated by the increased work load in his shoulders during wartime. Penelope Douglas

mentions his gout, adding that he suffered from this despite the fact that he ‘only drank wine

occasionally’. There are several brief references to his health problems in the press when, for

example, he was unable to attend meetings due to being ‘indisposed’. There was one particularly bad

flare-up of gout in 1920/21. In December 1920 it was reported that he was ‘indisposed and is

prevented from attending to his Parliamentary and other duties’. In April 1921, it was confirmed that he

was suffering with gout . The next month, he was ‘unable to return to Westminster after a serious

attack of gout’. In June, a news item noted that he ‘was making a good recovery in France from the

severe attacks of gout and rheumatism which have been distressing him for some months’. Another

report in that month stated that he was at Aix Les Bain and that he ‘couldn’t walk’. He was at Temple

Dinsley (perhaps convalescing) when the 1921 census was taken on 7 June. Later that month, it was

noted that he was in Town again after his ‘cure’ abroad - and yet was still indisposed. On 12 July 1921,

a newspaper commented that (Douglas Vickers’) health has been causing anxiety’. It was hardly

surprising that when the election was called in 1922, he retired as an Member of Parliament ‘in view of

the state of his health and the many business calls’.

The following news reports might hint that living in London might not have been the best place for

Douglas in view of his health problems:

Might the move to the Preston countryside have been partly prompted by health considerations?

A further reason for another home near London may have been Katherine’s activities at Chapel

House during the war, which were described by Penelope Douglas:

1

1

Finally, it might be remembered that when Temple Dinsley was offered for sale or rent, one of its

greatest attractions was the opportunity for field sports that it offered - “It is in a favourite hunting

district....the sporting capabilities are of a high character and afford excellent partridge and pheasant

shooting”. Douglas was at Tulloch Castle for the late summer/September shooting. Did he value a

mansion near London where he might indulge his sport. perhaps in company with friends from

London?

One or more of these considerations may have prompted the purchase of Temple Dinsley - but there

is nothing definitive on record that can be found. The simple fact is that the estate was bought.

Somewhat surprisingly perhaps for a Sheffield steel magnate, Douglas’ agricultural interests were

highlighted in a press release dated as early as 11 May 1918:

Meanwhile, concerning the of Home Farm on the Hitchin Road, The History of Cricket at Preston

states, ‘Some derelict farm buildings stood on the land now occupied by (Council Houses on the

north side of Chequers Lane) and these rude sheds were to be the first ‘pavilion’ when cricket started

in 1919.’ It continued, ‘The Recreation Ground, as we now know it ,was part of the farmland of

Brown's (Home) Farm, the ruins of which for many years remained where the Corporation yard is now

situated (in 1967)’.

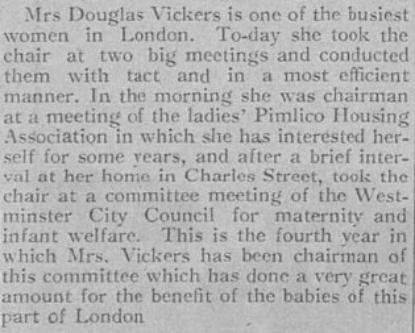

Of The Hon. Katherine Adelaide Vickers

We interrupt this history of the Vickers and Temple Dinsley with an

appraisal of Mrs Vickers.

Her noble roots have been commented on. Assessing her

activities, she became a strong, emancipated lady of society.

Some of her work during WW1 has been mentioned. Her annual

diary included a stay at Cannes, France during January and a

lengthy sojourn at her family’s Tulloch Castle in late summer.

In between, she organised regular events in London, often centred

on Chapel House, which were reported in the press together with

appreciative comments centering on what she happened to be

wearing.

The Vickers at Temple Dinsley

Although Douglas owned Temple Dinsley for more than a decade, there is a surprising lack of

comment about the activities of his family there. Apart from his investment in Wessex Saddleback

pigs at Castle Farm (about which we will comment later), there are only a handful of news snippets on

hand that mention the Vickers at the mansion:

This item is particularly of interest (despite its obvious editing) because it reports Mrs Vickers interest

in Preston’s Women’s Institute. In around 1920, her husband demolished four houses along School

Lane from the school to Preston Green (see below, left) and had the present-day bungalows built on

part of the site - one of which was given to his wife as a meeting place of the WI (below).

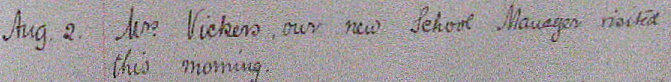

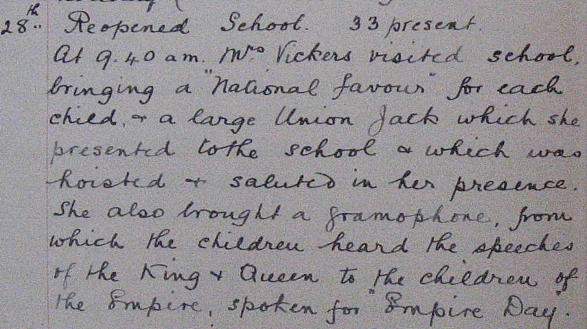

The Preston School log book provides probably the best partial diary of the Vickers stay at Preston -

Mrs Vickers was a School Manager (which likely signals an intent to stay in the village at that time)

and often visited the school in the first years of their residence in the village. In 1919 and 1920, she

visited six and five times respectively; from 1921 until 1924, her visits were once or twice a year but

from 1925, there is no record of her going to the school.

2 August 1918

24 August 1918. Mrs Vickers and friend visited and heard the children sing and some read to her.

4 December 1918. Mrs Vickers had promised a plot of ground (probably in the nearby allotments) for

a school garden and this was now available. (Note: activities in the garden were subsequently

frequently noted in the log book, not least because lessons had to be rescheduled due to bad

weather)

27 January 1919. Mrs Vickers visited, bringing flannelette for needlework.

12 February 1919. Mrs Vickers called regarding the school dinners given from next week at 2d a

head. She arranged for soup to be sent for children who stay for dinner.

12 May 1919 Mrs Vickers called with a watch for Sidney Peters, the first boy to knot a pair of

stockings. She also checked the register.

11 June 1919. Mrs Vickers and friend called.

3 October 1919 Mrs Vickers checked the registers

13 October 1919 Mrs Vickers called with some material for pinafores.

27 September 1920 Mrs Vickers visited.

11 October 1920 Mrs Vickers called with a large doll for the girls to dress.

18 October 1920 Mrs Vickers donated a sewing machine to the school.

22 December 1920 Mrs Vickers visited.

23 December 1920 Mrs Vickers distributed prizes.

14 February 1921 Mrs Vickers visited.

15 April 1921 Mrs Vickers checked the registers.

13 March 1922 Mrs Vickers visited

28 May 1923:

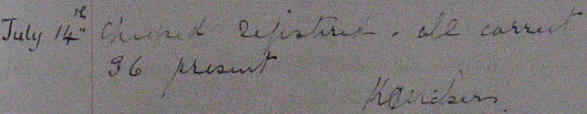

14 July 1924:

21 July 1924 Twenty-five older children treated by Mrs Vickers to visit the Wembley Exhibition.

Mr and Mrs Vickers were frequently mentioned in Sheffield and London newspapers (more than 1,700

times between 1914 and 1929) and it is possible to fill the gaps between visits to Preston School to

form an impression of when the family were in the village. In truth, it wasn’t often because of Douglas’

business commitments, Katherine’s interests and their social rounds.

If Katherine’s school visits are any kind of barometer to the Vickers’ occupancy of Temple Dinsley,

they were in residence frequently from late 1918 until the end of 1920; spasmodically until the

summer of 1924 and then very seldom, if ever, until the mansion was sold.

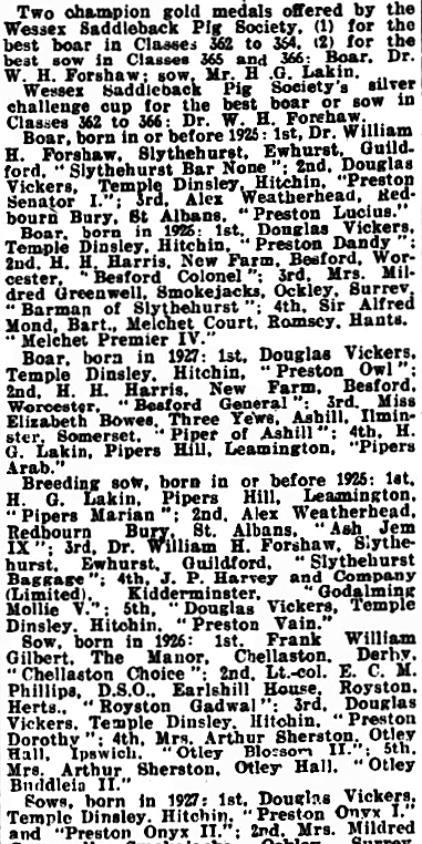

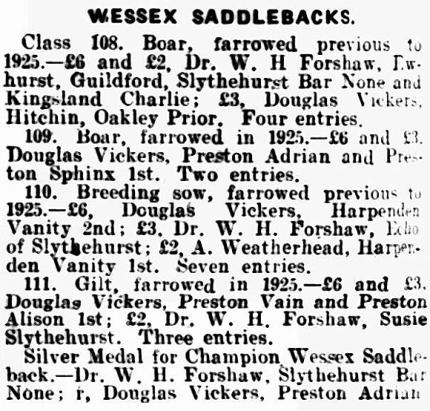

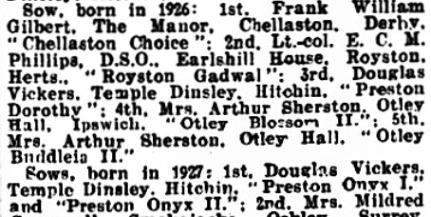

Douglas Vickers’ herd of Wessex Saddleback pigs at Castle Farm

From the early 1920s until 1959, Castle Farm was the home of ‘Herbie’ and Phyllis Jenkins, my great

aunt. Douglas funded the creation of a prize-winning herd of Wessex Saddleback pigs. These were

managed by his estate manager, Reginald J W Dawson, but the day-to-day running of the herd was

‘Herbie’s’ responsibility. He was described in 1951 as a ’Pig Farmer Herdsman’.

The herd was established by 1921, so it is likely that ‘Herbie’ was engaged from its inception. To

illustrate the scale of the operation, from 1921 upwards of 1,000 pigs were reared each year. After

1925, the herd received 500 awards at leading shows. A quick trawl through news reports of the time

reveals almost 200 references to Vickers’ ‘Saddlebacks’. One consequence of this breeding success

was that the village of Preston was publicized as several prize pigs were christened Preston this-or-

that. So there was ‘Preston Laurette’, ‘Preston Officer’, ‘Preston Dilly’, ‘P Orient’, ‘P Spot’, ‘P Dell’, ‘P

Senator’, ‘P Vanity’, ‘P Onyx’ and so on. A sample of the news reports from 1927 and 1925 follows:

Winning so many competitions throughout England with Saddlebacks named after ‘Preston’ would

have brought Douglas much pleasure and publicity and put Preston and Temple Dinsley ‘on the map’.

Link: Castle Farm

Suggested reasons for the sale of Temple Dinsley in 1929

Once again one enters the uncertain world of speculation when attempting to explain why the Vickers

began the process of selling Temple Dinsley in 1927.

If the house was bought in part as a venue to entertain Douglas’ friends and acquaintances as a

result of his position as a Member of Parliament, there was no need for it after 1922, when he

resigned his seat.

Douglas’ health didn’t improve after 1918, and became markedly worse after 1921. He was sixty-six

years old when Temple Dinsley was once again put on the market - with another ten years to look

forward to, as it transpired. It is hard to consider this as a reason to leave ‘quiet Hertfordshire’.

Perhaps the main reason for leaving Preston had to do with Douglas’ business affairs. When his

uncle, Albert Vickers, died in 1919, Vickers Ltd was ‘the first armaments firm in the country’. It reached

the pinnacle of its prosperity in 1913 and was valued at £25 million in 1915. World war created great

pressure on the firm and Douglas because of the ‘vast number of orders’. However, after the war, any

armaments company was going to struggle when the world was looking for a period of peace. Vickers

Ltd considered alternative areas of production such as making aircraft and the successful journey of

a Vickers/Vimy aeroplane to Australia ‘showed enormous possibilities’, But it was not easy for a heavy

industrial firm to now make ‘swords out of plowshares’ (a biblical phrase which was often used to

describe Vickers’ search for peace-time products). Douglas himself alluded to the difficulty of

switching from the manufacture of guns to gramophones.

Anthony Sampson in The Arms Bazaar wrote that Vickers (Ltd) was ‘bewildered by the problems of

peace’.

All of these factors culminated in this news release dated 6 December 1927:

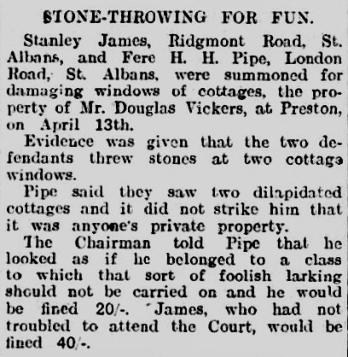

A summary of how Preston benefited from the tenure of the Vickers family

Douglas altered the landscape of the village to some extent. He pulled down

Temple and Home Farms - and had the imposing Crunnells Green House

(designed by Lutyens) built for his estate agent. The tumble-down cottages

along School Lane were demolished and replaced by four bungalows which

included a base for the Women’s Institute to meet.

However, as the local landowner, there was a need for more levelling of

properties which were in a deplorably dilapidated state - the houses on the

north side of Preston Green being a case in point. This news report from

1925 probably relates to their condition:

Not to be quickly dismissed is the opportunity of work for villagers that Douglas provided. A quick and

incomplete count of folk who worked for him in 1921 included seventeen labourers, a carpenter, an

estate agent, a building foreman, a typist, three keepers/woodmen and five gardeners.

Douglas also seems to have been sympathetic towards requests by villagers. He gave permission for

the meadows of Home Farm to be used as a cricket ground - but he was reluctant for that land to be

used as a football pitch. The football club was allowed the use of the meadow behind the Pavilion.

It was probably during Douglas’ tenure of Temple Dinsley that my grandfather lost a leg while working

in its woods. His family were allowed to live in Chequers Cottages rent-free thereafter. A family story is

told of my aunt, Flossie, that as soon as she heard that the cottage at Chequers Lane (where she and

her parents lived) could be bought, she visited the owner, Mr. Vickers, and purchased it.

Katherine supported the Women’s Institute and Preston School, being a School Manager.

I’ve singled out Douglas and Katherine’s son, Oliver, for comment because he had a significant

connection to Preston, as will be explained. He enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps on 7 November 1917

and Penelope Douglas recounts some his exploits, courtesy of her great aunt’s notes:

There were other external obstacles to trade. In 1925, Douglas complained that business was

suffering because foreign customers couldn’t raise a loan in the UK to buy armaments due to the

‘drive for world peace’. There were trade barriers - tariffs, special licences and prohibitions. When the

Chancellor of the Exchequer advised Vickers Ltd to re-direct its energies from armaments, Douglas

retorted that they had been ‘struggling to do that for ten years’. This business climate and the

economic slump of 1926 created a financial crisis for the company. Shares were written down to a

third. This spawned re-organisation and reconstruction for Vickers Ltd - part of which saw Douglas

resigning as chairman to become a titular ‘President’. In 1927, the Bank of England forced an

amalgamation when Vickers Ltd merged with Tyneside-based engineering company, Armstrong

Whitworth (which had been experiencing similar problems), to become Vickers-Armstrongs.

While not suggesting in the least that Douglas was personally struggling financially (his estate was

valued at £219,710 in 1937), clearly all of this activity exerted huge stress on him and not having the

upkeep of a mansion in Hertfordshire to add to his burden may have been appealing.

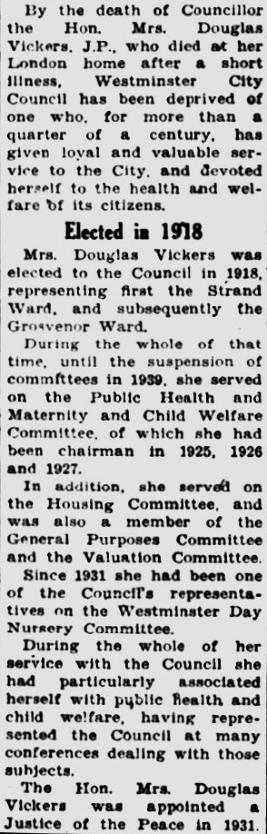

Perhaps more than this, Katherine’s activities in London (as described above) were consuming her

time and energies. Her work in the capital appears to have increased from around 1925 so that the

chore of checking the Preston School registers must have seemed a world apart.

Douglas Vickers - the man

Of Oliver Henry Douglas Vickers (1898 - 1928)

Douglas was described as a ‘quiet reserved man with clever

demonstrative manner’. The cartoon (shown right) by ‘Spy’ in Vanity

Fair is said to have ‘well-captured’ his persona.

Penelope Douglas described her aunt’s recollections of Douglas:

Penelope said of Douglas;

A news report noted Douglas’ ‘philanthropy, for which he was well

known’. It was demonstrated by this gift to Hitchin historian, Reginald

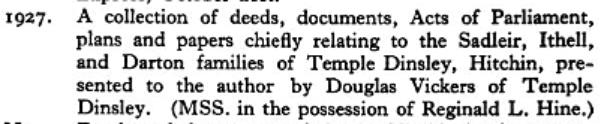

Hine:

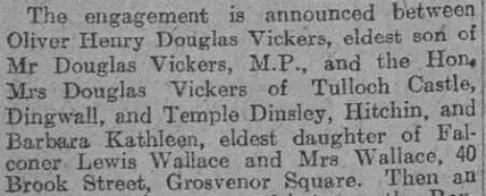

On 1 March 1920, Oliver announced his engagement to Barbara Wallace. The couple married shortly

afterwards in April of 1920.

In June 1921, Oliver and Barbara were counted at Temple Dinsley in the census, together with his

parents and two visitors who, from their connection with the RAF, were likely to have been among his

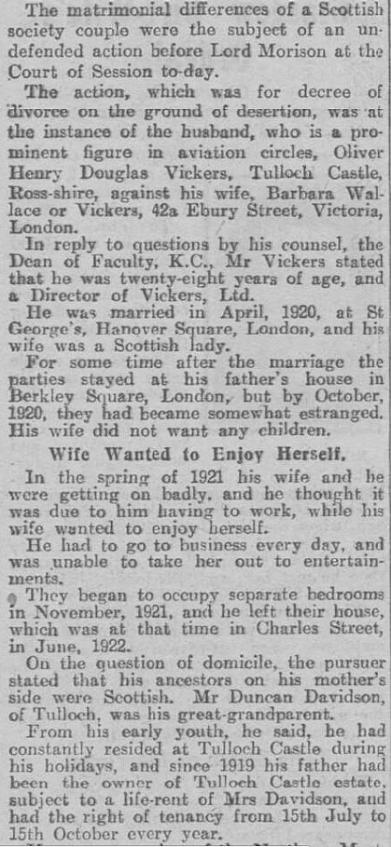

flying Service companions. Unfortunately, it transpired that shortly afterwards the marriage foundered:

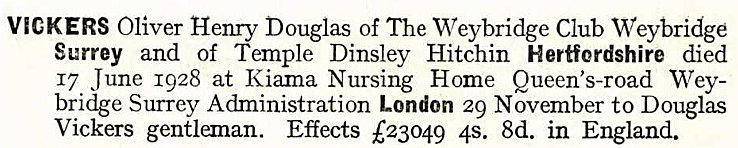

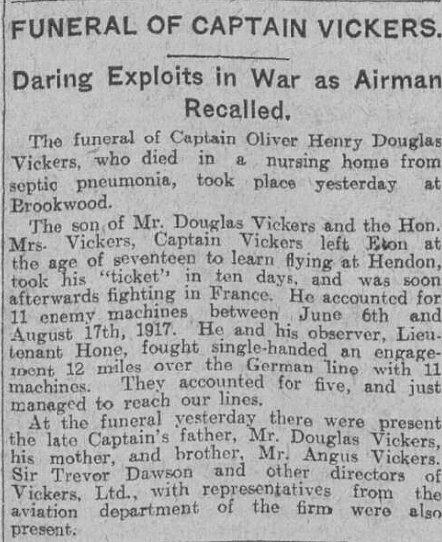

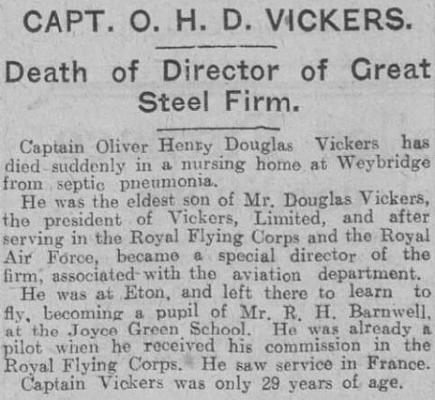

Tragically, Oliver died on 17 June 1928 of septic pneumonia:

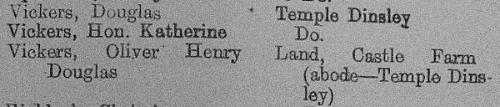

Oliver’s connection to Preston is suggested by Temple Dinsley being given as one of his addresses

when he died. But his links are especially indicated by the 1925 electoral register which notes that his

home was Temple Dinsley and that he held land at Castle Farm, Preston (where his father’s

Saddlebacks were bred):

There is an abstract of title of the trustees of the marriage settlement of Edward Spencer Curling and

Gladys Emily Curling to Preston Castle Farm with land in Hitchin and Ippollitts, Hertfordshire, and six

cottages in Hitchin Road and Chequers Lane in the village of Preston, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, 1919-

1920, with copy conveyance of the properties by the trustees to Oliver Henry Douglas Vickers of

Temple Dinsley, Hitchin, Hertfordshire, 1920. The properties comprised in these papers apparently

form part of a marriage settlement from his father.

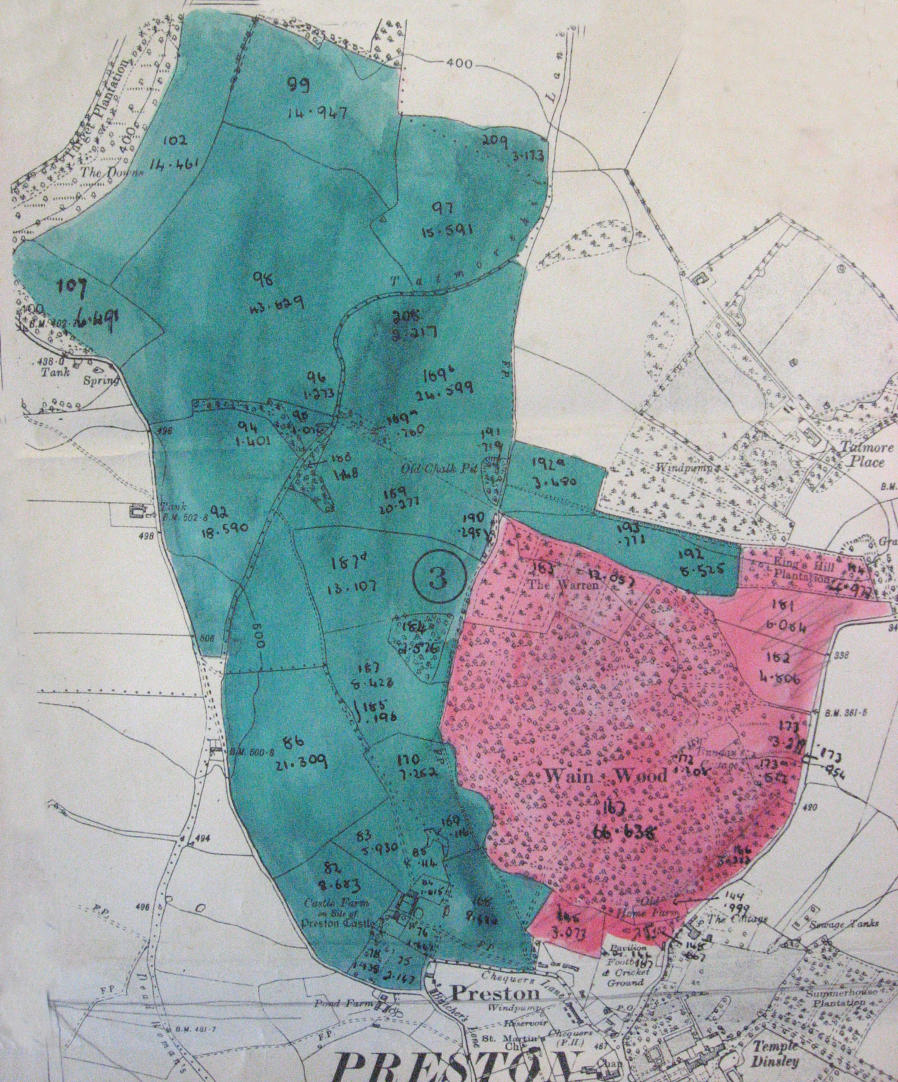

From 1920, Oliver owned Castle Farm and six houses on the north side of Chequers Lane, Preston

(Link: Chequers Lane). The considerable area (not including the six houses) covered is shown in

turquoise below on this hand-drawn map. Wainwood (depicted in pink) was owned by Douglas

Vickers and didn’t form part of the gift to Oliver.

Castle Farm

The 6 cottages on

Chequers Lane

(A description of Douglas Vickers’ holding at Preston will be added soon.)

1924