Preston’s Farms: Castle Farm

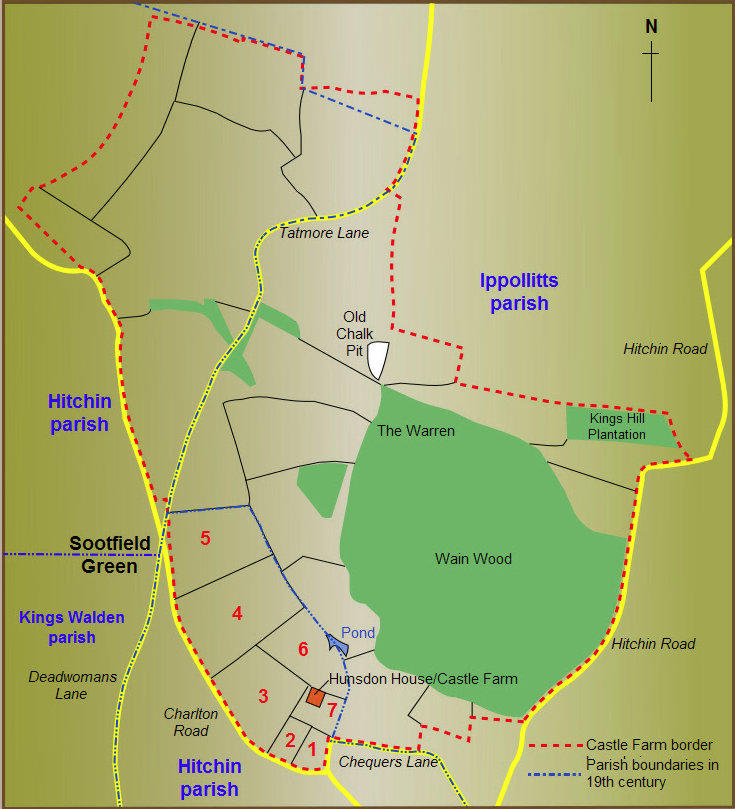

Castle Farm estate in 1945

Note: Wain Wood and land surrounding

it to the south-east, east (sandwiched

between the wood and the Hitchin

Road) and to the north was owned by

the Radcliffe family and was sold to

James Barrington White of Temple

Dinsley in 1902.

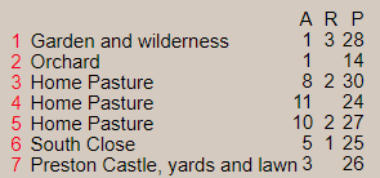

Hunsdon House aka Castle Farm in 1844

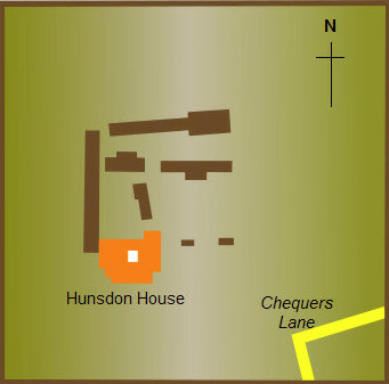

Castle Farm in 1898

To the north of Chequers Lane at Preston, a mansion, Hunsdon House, was built near the site of

Preston Castle. Nearby was a well which was 270 feet deep. Hunsdon House fell into disrepair in

the early nineteenth century and was a ruin by the 1850s. Nearby, a stable was converted into a

farmhouse – but this was destroyed by fire in 1868. Castle Farm, as it is known today, was then

built and a lodge was added in the twentieth century.

The area of farmland (which is both arable and pasture) associated with Hunsdon House and Castle

Farm was remarkably unchanged between 1861 and 1945 at about 278 acres. It included a chalk pit

and a pond to the north of the farm that was large enough to provide water when the fire brigade

attempted to save the house and buildings in 1868. The land was divided by the parish boundaries of

Hitchin and Ippollitts and fell within the manors of Temple Dinsley and Maidencroft.

The farmland bordered Wain Wood which was owned in the nineteenth century by the Radcliffe

family. In 1945, when Castle Farm was sold, the 95 acres of Wain Wood was included as part of the

package.

The Foster family and Hunsdon House

In the 1660s, Hunsdon House at Preston was home to the Foster brothers – six of them (three

married, three bachelors) lived there. The owner of the mansion was John Foster and he and his

family farmed the land which is today known as Castle Farm.

They were ‘intimate friends and enthusiastic followers’ of John Bunyan, offering the preacher a

welcome and shelter in their home during troublesome times. They were ‘steadfast and true men’,

‘distributing to the necessity of saints, given to hospitality’. More than once, because of their

knowledge of the lie of the land, they were able to spirit Bunyan away from the troops searching for

the dissident who had surrounded Wain Wood.

On one occasion, ‘Bunyan was sitting with the Foster Brothers in their house at Preston when

someone asked him to explain a biblical verse....(he replied) “all that I can say in answer to that

question is that the Scripture is wiser than I”’.

When the Great Plague swept through London in 1665, some fled to Hitchin carrying the deadly

disease. In one month alone, more than thirty died of the plague. During the panic that ensued, the

Baptist followers of Bunyan were almost the only ones who risked their lives to minister to the sick.

Included among them were the Fosters, whose disregard for their own well-being won the admiration

of their opponents.

It is told that during the time of Bunyan’s imprisonment, when a sympathetic jailer allowed him leave

of absence in advance, he was met by one of the Foster brothers with two horses and a farm labourer

was left behind in his stead while Bunyan rode away to preach to his flock.

Later, Bunyan arranged for his second-in-command, John Wilson, to minister to his followers in the

area around Hitchin. After his trial in 1677, there was a church meeting at Brother John Foster’s

home. When, Wilson was incarcerated in Hertford Gaol, more than fifteen miles away, each week

one or more of the devoted Fosters travelled from Hunsdon House to Hertford with a ‘basketful of

fresh country-fare’ to sustain him.

The Fosters were among the founder members of the Baptist Meeting House built at Hitchin in 1692.

When Wilson was succeeded by John Needham in 1705, Needham was met in the vestry of the

chapel by Edward Foster and told, ‘And need enough we have of you’.

Several Fosters and their descendants served the Hitchin Baptist Church for three hundred years –

when the new church was built at Tilehouse Street at Hitchin in 1844, among the speakers at its

inauguration was John Foster, then of Biggleswade. When Bunyan’s Chapel was built at Preston in

1877, the two foundation stones were laid by Edward and Ebenezer Foster, descendents of the

Hunsdon House family. The foregoing may not tell much of Hunsdon House and Castle Farm but it

does inform us about the character and beliefs of its owners and a frequent visitor almost three

hundred and fifty years ago. More can be gleaned from this article - Link: Of Sterne

Later owners of Hunsdon House/Castle Farm

The Maidencroft manorial roll reveals that the Fosters sold Hunsdon House and its farmland to

Joseph Roberts. In 1723, Roberts sold the property and land to Robert Hinde (1st) who financed the

purchase from the profits of his brewing business at Holborn, London. When Robert died in 1737, his

son Robert (2nd) inherited the estate. In turn, Robert’s (2nd) son, Robert Hinde (3rd) was bequeathed

the property in 1755. His life is described in a separate article. (Link: Capt. Robert Hinde)

After his army career, Robert applied himself to farming – yet his military training asserted itself even

in this pursuit. When he summoned and dismissed his labourers, it was proclaimed by a chorus from

his Light-Horse bugle. However, he took his farming seriously – ‘I pursue the following method: wheat

after the fallow, then peas, turnips, barley, oats, clover, wheat’. He suggested improvements to Arthur

Young’s swing-plough and trialled the Hertfordshire great-wheel plough and the one-handle Essex

plough.

When Robert Hinde (3rd) died in 1786, the house and land was passed around his sons, John,

Samuel and Peter until it was sold to the beast salesman, James Earl in June 1815. (Link: James

Earl) Five months later, Earl sold the property to William Mellish. He allowed the house to quickly

deteriorate and five years later Mellish sold his holding to a group comprising: Revd. George Millett,

Thomas Flower Ellis, John Hayton and William Davies.

In 1820, the consortium sold the mansion and land to William Curling (snr) and it remained in his

family for more than a century being passed down to William’s son, William Curling (2nd) (1842),

William’s (jnr) wife, Flora Jones Curling (1865) who sold the property to her son, Major Edward

Spencer Curling (1904). Major Curling purchased the freehold to the property in 1919. The estate was

sold in 1945 and is now part of the Pilkington estate.

Occupants of Castle Farm from 1837

John Wright (1837 - 41c)

George Wright

Samuel Kirkby (1851 - 1861c)

Stephen Marriott (1871 - 1885c)

Charles Davis (1886)

John Dew (1891-1905c)

Joseph Thrussell (1910 – 1915c)

Ernest and Christobel Smith (1920)

Herbert and Phyllis Jenkins and Frank Currell; Joseph and Mary Armour. (1925)

Herbert and Phyllis Jenkins and Frank Currell ; Eli and Daisy Free. (1930)

Herbert and Phyllis Jenkins; Ronald and Eileen Foster. (1951 - 1955)

Horace and Doreen Jenkins; Miriam and John Bartlett; Arthur and Hilary Dearmer. (1961)

Horace and Doreen Jenkins; Miriam and John Bartlett; Doreen and Michael Brown. (1966)

Ian and Ann Clark (1971 -)

(Note: Castle Farm farmhouse, built around 1870, was divided into two homes in the 20thC)

Hunsdon House becomes a ruin

After Robert Hinde’s occupation, the mansion quickly became abandoned. On 8 May 1832, there was

an advertisement to let Preston Castle which provided a glimpse of its features:

The approach, past a neat entrance lodge, was by a gravelled road through a meadow. There were

four bedrooms and a large bedroom for servants on the upper floor of the mansion. On the first floor

were three spacious apartments opening into a gallery, dressing room, water closet, three other

bedrooms, apple room and staircases. The ground floor had a drawing room (30’ x 20’), a dining room

(20’ x 18’), a billiard room, kitchen, pantry, servants’ hall, wash-house and dairy. There were also wine

and beer cellars.

The outbuildings included a double coach house, five-stall stable over which was a granary and a loft,

a coal house and wood barn. There was a 23-feet long greenhouse adjoining the breakfast room, a

20-feet long grapery and a mushroom house. The grounds occupied four and a half acres,(including

the Wilderness) which were thickly studded with lofty firs, chestnut and lime trees. There was a well

planted orchard and garden and walks ornamented with evergreens, American and other flowering

shrubs.

In 1873, the daughter of William Curling wrote these poignant observations about Hunsdon House:

‘This old country-house was then unoccupied, and standing, forsaken and dilapidated, in the midst of

its still beautiful gardens. A narrow lane, running south from Preston, led you to a simple lodge. You

then passed through meadows, well fenced with hawthorn and holly, to the north front of the house.

Over a low, strong hedge of sweetbrier, you saw a massive grey porch, a little overhung with virginia

creeper; venerable casements looking out on the broad carriage-road which led to the hall-door, and

a circle of flower-beds with a central sun-dial. Wide walks, fair lawns, huge evergreens, each one a

kingdom of leaves, met the eye as you entered the gates. Well do I remember those grounds, and the

wood of pines and chestnuts at the end of them! In the gardens, one saw everywhere a happy

blending of modern art with the dear, old, stately formality of other days. But the house had suffered

loss at the bands of some individual who had preferred convenience to the charms of antiquity ; and

had been still more injured by another, who had given a castellated front to a pile half manorial, half

Georgian. Preston Castle, when I remember it, stood silent and forsaken, a fit haunt for the ghosts of

my childish imagination. The ancient hall and many chambers centuries old, were on the north side;

on the south were the Georgian rooms. Even there, one's footsteps echoed strangely, and the mid-

day sun, passing into them through an outer blind of sweet roses, starry jasmine, and climbing

creepers, could not lighten the gloom within. The sight of the mildewed walls, the faded, falling

papers, the blank, deserted hearth, would have saddened any heart but that of a child, full of "life, and

whim, and gaiete de coeur"’.The full text of Miss Curling’s article in Gentleman’s Magazine can be

found here: Link: Hunsdon House.

The mansion was eventually sold to William Mellish a few years later and sold off as building material.

The battery of guns became scrap metal (except two which found their way to Preston Hill Farm); the

gazebo was used to repair a Kings Walden pigsty; the lawn reverted to pasture. Even the avenue of

walnut trees (remembered fondly by those who walked between them - including myself) which led

from Chequers Lane to Castle Farm, is no more. The Lodge was destroyed by fire in 1912. Only the

name remains – ‘Castle Farm’ – which adorns a nearby farm. There is also a two hundred and

seventy-feet deep well which is thought to be the original well of Preston Castle.

Castle Farm 1837 to 1868

The farmhouse of Castle Farm was converted from stables. The 1837 Rates Book and 1841 census

show John Wright (born 1761c) occupying the farm. John’s son, Samuel died there in 1839. John

himself died of debility on 11 December 1841 (the informant was Mary Jeeves; he left legacies of

more than £1,750) and his son, George Wright, briefly took over the tenancy but between 1845 and

1851 George moved to Preston Hill Farm. (Link: Preston Hill Farm).

By 1851 Samuel and Dorothy Kirkby were at Castle Farm. Samuel was appropriately born at

Hunsdon, Herts in 1807. He and Dorothy had seven children of whom one, Emma, married Frederick

Armstrong of Preston Hill Farm (Link: Armstrong). In 1861, Samuel was employing eight men and

five boys at Castle Farm. In 1862, one of his labourers, John Fitzjohn of Sootfield Green, left Samuel’s

employ ‘without cause’ thinking that he could earn more elsewhere. Another worker, John Sharp was

labouring at Castle Farm, when Samuel’s son, James, asked him why he wasn’t at work one day.

Sharp responded by hitting James and his horse with a stick.

Castle Farm destroyed by fire

Samuel Kirkby was still at Castle Farm in the summer of 1868 when fire destroyed the farm, its

outbuildings and much of the harvest. It was dramatically reported in the Hertfordshire Express:

“Some years have elapsed since any fires have occurred in the neighbourhood of Hitchin so

destructive as those we now have to record.

The first was at Preston Castle Farm, about three miles from Hitchin, belonging to Mrs William Curling

and in the occupation of Mr Kirkby. The farm is about 300 acres in extent and a larger proportion than

usual had this year been sown with wheat. There were also some fair crops of oats and barley, besides

hay, both old and new. The whole of the year’s produce was garnered in barns and stacks near the

house, which, with outbuildings, formed a kind of oblong square, enclosing the fold and rick yards. The

house itself faced towards Hitchin and was a long, low range of a brick building, with a well house and

lumber room at the upper extremity, nearest the village of Preston; the lower extremity joined on to the

stabling etc., being connected with the outer range by a small thatched wood-house.

The mansion known as The Castle was pulled down some twenty years ago and the farmhouse just

destroyed was converted from the stabling of the old house. The old place was historically interesting

as being the supposed scene of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy; and it is almost certain that the chief

characters in that racy work, including Uncle Toby and Corporal Trim, were delineated from local

celebrities with whom the author became acquainted during his periodical visits to the Whittingham’s,

the Hinde’s, and other local families then residing in the neighbourhood.

The fire was discovered shortly before eight o’clock on Saturday morning by one of the men working

on the farm. He called the attention of Mr Kirkby’s son to some smoke issuing from the long barn or

granary standing in front of the house and which was filled half with wheat and half with barley. An

alarm was immediately given and of course the family and all about the place were thrown into a state

of excited consternation. But a few minutes elapsed before Mr Kirkby had mounted a horse, galloped

to Hitchin, given the alarm of the fire and called out our local fire brigade. They received intimation of

the fire about a quarter after eight and by the time that four horses had been attached to the largest of

the engines, the following firemen were equipped and ready to start: Messrs. F Latchmore, F Shillitoe,

E Logsdon, G Pack, J G North, J Throssell and W Hill.

By the time the fire engine arrived, the greater portion of the damage was done and the flames had

got complete mastery over the whole area. A light shifting wind blew all the morning, driving flames

and burning sparks hither and thither from point to point of the property. From the granary in which

the fire began, it crept to another and so from stack to rick, from rick to barn, until it made its circuit

round to the stabling and having seized on the thatched wood house already referred to, got hold of

the dwelling house, which was quickly wrapped in a sheet of fire. So intense was the glare that even

in the brightness of the morning sun, the forks of flame showed lurid red high in the air and attracted

spectators from places far distant.

It would seem to a visitor who came to the spot after the worse was over that much could have been

saved if the efforts had been made to circumscribe the limits of the fire by pulling down some of the

connecting links; but it is more easy to be wise after the event than to do exactly the right thing at

exactly the right moment. What those on the spot did in the first panic of excitement was quite right

and proper to be done. They got out the horses and other living creatures as far as they could from

the fiery circle which so rapidly surrounded them and carried out the greater part of the household

furniture and personal property from the house before the fire laid firm hold upon it. Some bedsteads

and other cumbrous fixtures that could not be hastily removed were left to their fate but most of the

moveables were saved.

The poultry flew into the neighbouring wood and kept up a distressful noise all day at being driven

from their usual haunts. Not all the stock was saved for the half-burnt carcasses of two large fat

calves and two young pigs were found among the ruins of the farmyard. It is said that the men about

the place cut the flesh from the bones of these animals and ate it half-charred and half raw as it was:

for certain, the meat had been stripped from the carcasses and nothing was left but red bones and

entrails in the afternoon. So great was the heat that the fruit on the adjacent apple trees was baked

as it stood and this too was eagerly devoured when the fire subsided.

It was late in the afternoon before the fire had spent its fury. The farmhouse, the barns, the corn

stacks, hay ricks, implement shed, stables and all were reduced to a heap of smouldering ruins,

emitting fitful flashes of flame as the wind puffed round the embers. The upper end of the homestead,

consisting of the well house before-mentioned had been saved, for the firemen had mounted the tiles

and with their axes cut away the roof of the building so as to break the further spread of the fire. Also,

they managed by dint of great exertion to save one large wheat stack at the more distant extremity of

the yard, but this, although rescued from destruction, was damaged by water and smoke. A very large

quantity of valuable hay was destroyed including two ricks of old hay and the produce of this year’s

crop. Besides the wheat, barley and oats there were two ricks of oats and some dressed vetches. It

was pitiful to see the grain, left unconsumed by the fire, trampled underfoot in all directions. The hay-

stacks smouldered obdurately in dangerous proximity to the wheat stack that was saved and the

firemen played upon the burning mass until the pond was pumped dry and nothing but thick mud

remained. Then the engine limbered up and brought back to Hitchin on Saturday night. Between

twenty and thirty men – mostly labourers - worked the engine during the day, some of them standing

up to their knees in water for hours.

The unobtrusive heroism of a young married labourer named John Jenkins deserves special

attention. His task was to raise water by means of a windlass from the well at the end of the house,

said to be 270 feet deep: he worked away at his arduous task for several hours with uninterrupted

energy until at length he fell back senseless. He was laid down on the grass outside until medical aid

arrived from Hitchin: then it was discovered that his heart was suddenly affected by excitement and

unwonted exertion and he was carried home. For some hours his life trembled in the balance; but we

are glad to hear that a favourable reaction set in on Sunday and that he is now recovered.

The numerous family of Mr Kirkby was thrown into great fright and commotion, as may be supposed;

but they all found temporary refuge under the hospitable roofs of neighbours and friends.

We are informed by men on the spot that the origin of the fire is quite a mystery; that the granary

where it broke out was locked up in safety on the previous night and had not been since been opened

and that when the fire broke out only two workmen were known to be about the place. In the absence

of any reasonable explanation of how such a catastrophe could have been caused, the surmise is

that the fire was caused by an incendiary. The police are inclined to attribute this fire to accident. The

fire burnt with fluctuating vigour for several days and attracted numerous visitors from Hitchin and

surrounding villages. Mr Kirkby was fortunately insured in the County Fire Office, the damage is

estimated at between £1,500 and £2,000. The buildings were insured in the Royal Exchange Office.”

Although Samuel Kirkby was still at Castle Farm at the end of 1868 (William Pedder stole nine turnips

from him in December) perhaps the trauma of the fire and the effort of rebuilding the farm was too

much for him – he was 61 years old. He gave up the farm and moved to another farm at Eastwick,

Herts. In 1871, Castle Farm had a new tenant - Stephen Marriott.

Stephen and Emma Marriott

The new tenant farmer at Castle Farm in 1871 was Stephen Marriott. Born in around 1824 at Milton,

Northants, Stephen had been farming at Toddington, Beds. before his move to Hertfordshire.

Among the news stories mentioning Stephen was a charge of killing three pheasants out of season in

1876. He claimed that he thought they were smaller partridges and escaped a fine. Among his

labourers in 1876 was George Hawkins of Hitchin. It seems from the court case in which Hawkins

was accused of theft that Stephen settled his labourers wages in The Chequers public house. In

1879, Stephen grew a crop of beans. Stephen died in the winter of 1883. His widow, Emma, moved

to Rose Cottage, Chequers Lane and died in early March 1908.

John Dew

John Dew was born in Cambridgeshire circa 1824 and occupied Castle Farm from approximately

1884 to 1905. He was also a surveyor of highways around Preston.

There was ill feeling between Dew and Preston hay dealer, Frank Brown. Brown was charged with

throwing a missile at Dew when Dew was driving towards Hitchin in 1891 and then threatened to

assault him. The following year, after Dew brought a charge of obstruction against Brown for leaving a

dog cart on the road, Brown threatened to ‘do for him’ and stated that Dew had ‘given him a great deal

of annoyance’.

‘On Monday morning at 9.30 a fire broke out at Preston which resulted in the destruction of the

picturesque lodge, tenanted by Mr. JG Dew, and standing in the field at the entrance to the Castle

Farm, which is owned by Captain Curling and in the occupation of Mr. John Dew.

The old cottage had something of an ecclesiastical appearance. Built of brickwork covered with

cement, the little building was remarkable for its Gothic windows with their diamond shamed lead

lights, while one end of the house had, as it were, a great Gothic moulding as if at some distant time a

large window had existed there. Moreover, on the plaster, covering the brickwork within the moulding

there appeared a rough representation in black paint of a diamond-paned window. Surmounted by a

thickly-thatched roof, the old building had always excited comment, and another local landmark has

now been added to the long list of those destroyed by fire.

The fire, it is thought, originated from a spark from the chimney falling upon the thatched roof. Mrs.

Dew was upstairs at, the time and as the thatch burst into flames she at once alarmed the villagers,

who gave ready assistance in removing furniture from the rooms beneath. The Hitchin Fire Brigade

were telegraphed for and it is worthy of note that, despite the distance of the fire station from the Sun

stables, from which the horses are supplied, the steam fire engine and the hose reel were on the way

to the fire exactly eleven minutes 'after the receipt of the telegraphic call. The brigade were under the

command of Captain Logsdon, Lieut. LC Barham, who happened to be in the neighbourhood, joining

the firemen at the scene of the fire.

Upon arrival at Preston at 10.30 it was seen that there was no hope of saving the burning building,

which now resembled a great, furnace. Attention was turned to the thatched houses whose roofs had

been well wetted and so further danger of their catching fire from falling sparks, was obviated. At

12.30 pm the fire had practically burnt itself out, only a portion of the walls and a chimney stack

remaining. The brigade thereupon returned to Hitchin, having made the further spread of the fire an

impossibility. The property destroyed included the house and several barns, with a considerable

portion of their contents. It is understood that the loss is fully covered by insurance.’

Castle Farm in the twentieth century

From the early 1920s until 1959 Castle Farm was the

home of Herbie (shown right) and Phyllis Jenkins, my

great aunt.

When Douglas Vickers owned Temple Dinsley, he built

up a prize-winning herd of Wessex saddleback pigs.

These were managed by his estate manager, Reginald J

W Dawson, but the day-to-day running of the herd was

Herbie’s responsibility – he was described in 1951 as a

’Pig Farmer Herdsman’.

The herd was established in 1921, so it is likely that

Herbie was engaged at its inception. To illustrate the

scale of the operation, from 1921 upwards of 1,000 pigs

were reared each year. After 1925, the herd received 500

awards at leading shows. A quick trawl through news

reports of the time reveals almost 200 references to

Vickers ‘Saddlebacks’.

One consequence of this breeding success was that the

village of Preston was publicized as several prize pigs

were christened Preston this-or-that. So there was

‘Preston Laurette’, ‘Preston Officer’, ‘Preston Dilly’, ‘P

Orient’, ‘P Spot’, ‘P Dell’, ‘P Senator’, ‘P Vanity’, ‘P Onyx’

and so on.

A wallowing ‘Saddleback’ at Castle Farm

The farm, together with Wain Wood and its surrounding fields, was sold to the Pilkington Estate in

1945. It became home to the Prescas herd of pedigree Holstein Fresian cows.

Castle Farm Lodge destroyed by fire in 1912