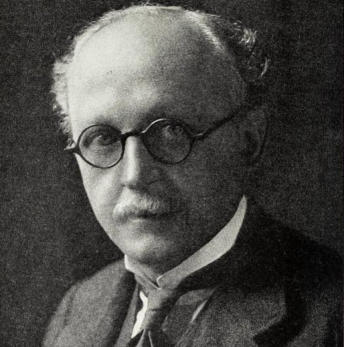

Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Lutyens was an internationally-renowned architect who left his stamp on Preston by

designing more than a dozen buildings in the vicinity.

This provides a uniform and pleasing character to the district.

Here is the story of his life and his involvement with a small Hertfordshire village.

‘The greatest artist in building whom Britain has produced’ – thus, Sir Edwin Lutyens has been

lauded. Between 1908 and 1920, he designed several properties around Preston ranging from estate

workers’ cottages to Temple Dinsley’s extensive additions and alterations.

Edwin Landseer Lutyens was born on 29 March 1869 at Onslow Square, London. He was one of

fourteen children and was known among his friends simply as ‘Ned’.

His daughter, Mary, asserts that her family descended from a Dutchman called Lutkens who came to

England and became a naturalised British subject, changing his name in the process.

Edwin’s father, Charles, held a commission in the 20th Regiment of Foot and was a talented water

colourist. In 1852, he married an Irish girl, Mary Gallway, in Montreal, Canada. Five years later,

Charles retired from the army with the rank of Captain to paint professionally. He studied with Sir

Edwin Landseer who was to be Ned’s godfather and the inspiration for his name. Charles exhibited at

the Royal Academy every year and, with Edwin Landseer, designed the lions of Trafalgar Square

Lutyens’ formative years

As a child, Edwin contracted rheumatic fever which influenced his development: ‘Any talent....was

due to a long illness which afforded me time to think’ and which taught him to ‘use his eyes instead of

his feet’. He had a talent for drawing – ‘It’s easy, I just think and then I draw a line around my think’.

As a teenager, he roamed the West Surrey countryside absorbing the styles of old buildings and the

methods of construction of new homes – how drains were dug; the laying of foundations; how roofs

were tiled and the erecting of chimney stacks.

Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll

In 1885, Edwin was sent to South Kensington School for Art. Four years later he was introduced to

Gertude Jekyll, doyen of English garden designers, a meeting which was to result in several

architectural commissions. Lutyens affectionately referred to Jekyll (who was twenty-six years his

senior) as ‘Aunt Bumps – the Mother of All Bulbs’ or ‘Mab’. Together, they toured the countryside in

Jekyll’s pony cart observing farms and houses and discussing their structures.

When he was twenty years old, Lutyens opened his own office. It was the age of the grand country

house where guests were entertained from Saturday until Monday and he established a reputation for

designing picturesque houses for the nouveau riche and country cottages. His first commission was

to plan Jekyll’s own home, Munstead Wood in Godalming, Surrey (1896).

Jekyll introduced Lutyens to those for whom she designed gardens and he planned architectural

features for homes and gardens. The ultimate kudos for many wealthy families was a “Lutyens house

with a Jekyll garden” - an ‘Edwardian catch-phrase denoting excellence, something fabulous in both

scale and detail’. Perhaps their best-known collaboration is at Hestercombe in Somerset which is still

a revered shrine for admiring gardeners

When studying for a gardening qualification, I was astonished to read of a Lutyens/Jekyll project in

my father’s old village. Jane Brown in Gardens of a Golden Afternoon (sub-titled, The Story of a

Partnership: Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll) mentions ‘another good brick garden with elaborate

terraces’ at Temple Dinsley and includes a photograph of the garden house. She lists ‘the rose

garden with its elegant brickwork’ as one of only twenty-four ‘saveable’ and ‘hallowed’ examples of

the duo’s work.

This is how Lutyens (described as the ‘leading architect of country houses’ because of a ‘brilliant

sequence of houses built for rich and fastidious Edwardians’) became involved with Preston: he had

designed additions to Abbotswood at Stow-on-the-Wold, the home of country gentleman, Mark

Fenwick to whom he had been introduced by Jekyll. Fenwick in turn recommended Lutyens to his

cousin, H. G. Fenwick, ‘Bertie’, who had purchased Temple Dinsley. H.G.F. commissioned additions

to the Queen Ann mansion and built the estate cottages at Chequers Lane, Preston. He also had Hill

End, Langley built for his wife together with a cluster of nearby cottages. Minsden Farm, now known

as Ladygrove, Kiln Wood Cottage and 1 & 2 Hitchwood Cottages were also commissioned during this

period. Thus, in less than twelve years, a collection of buildings, whether mansions or cottages, was

created around Preston village giving a uniform and pleasing character to the district.

Lutyens and Preston

Lutyens’ work evolved, his reputation grew and his designs became more grandiose: for twenty years

he planned the lay-out of New Delhi, India where he also designed the Viceroy’s house – all in a neo-

classical style. Lutyens was knighted in 1918. Following The Great War, he devised the Cenotaph in

London and the Memorial of the Missing of the Somme at Thiepval. He was also commissioned to

design several commercial buildings in London and the British Embassy in Washington, USA.

After becoming president of the Royal Academy in 1938, Lutyens died on New Year’s Day, 1944 and

his ashes were interred at St Paul’s Cathedral – an apt choice as he referred to his ‘Wrennaisance’

style at the time he designed the additions to Temple Dinsley.

Later work

Lutyens had the self-trained ability to memorize a building’s colour, texture and materials. A new

commission would take shape in his mind’s eye. On site, he might make deft, pencil sketches,

sometimes on scraps of paper, which ‘poured out like water from a jug onto the paper’ and included a

note of proportions. If clients were present during the moments of creation, they watched with

fascination as their house took shape before their gaze. Back at Lutyen’s office, the drawings were

then passed to an assistant who produced a correctly-drawn scale plan.

Rather like the artist’s ‘golden rule of thirds’, Lutyens also developed, by trial and error, a simple but

subtle system of ratios between dimensions and angles of a building which gave a distinctive

character to much of his work. He decreed that all inclined planes should be at 54.45 degrees; that

the intersection of two roofs should be inclined at 45 degrees and that window panes should have a

‘diagonal of square’ ratio which also gave the proportions of the whole window. If the building design

failed to conform to his methods, then the building was adjusted rather than the proportions. His

motto was ‘Metiendo Vivendum’ – ‘By measure we must live’ and he said of his work that ‘everything

should have an air of inevitability’.

Lutyens’ methodology

Navigate from here using links below to articles featuring photographs and

comments re: Luytens’- designed houses at Preston

Temple Dinsley

The gardens of Temple Dinsley

The rose garden of Temple Dinsley

Crunnells Green

Hill End and nearby cottages

Chequers Cottages

Minsden farm (aka Ladygrove),

Kiln Wood

1 & 2 Hitchwood Cottages