A History of Preston in Hertfordshire

John Hadfield of Sadleirs End, Preston:

‘bookman’ and cricketer

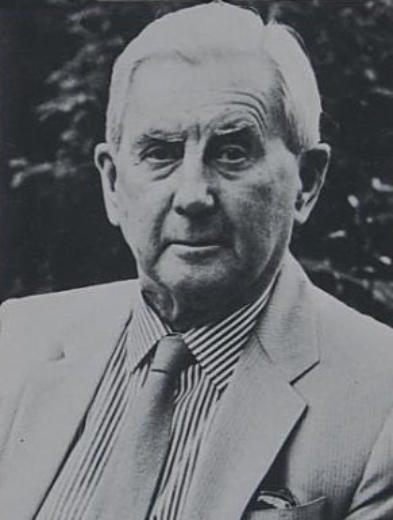

John Hadfield, who has died aged 92, was a "bookman"; the editor for 25 years of the Saturday

Book, a dab hand at anthologies and for two decades a director of the publisher, George

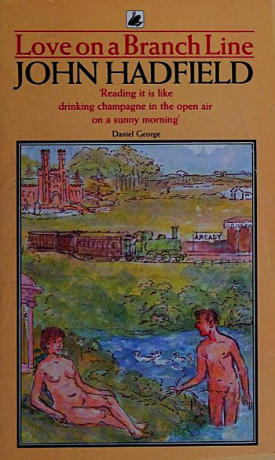

Rainbird. In 1959, his passion for art, cricket, jazz and East Anglia came together in the novel

Love On A Branch Line, which is light, witty, even sexy, and now even more nostalgic than in

the 1950s; indeed, it is imbued with all the oddball charm that its author brought to editing the

Saturday Book.

This annual hardback miscellany regularly sold out in the weeks before Christmas. Started in

1943, it had brought a lavish tinge to wartime book production, and in taking it over after the

war, Hadfield made a stand against the prevailing austerity. Profusely illustrated and elegantly

designed, it was a natural home for such items as, say, a piece on a passion for junk shops or

a history of beards - which pointed out that sages (Darwin, Tolstoy) tend to the long and

straggly, while extroverts sport the type favoured by the early TV chef Philip Harben. Another

was May Margaret Revell's discussion on her pet otters: having the freedom of her house they

slept below her bed, where, in the small hours, they amused themselves by waking her with a

tug at the springs.

Hadfield was a man of broad culture. He first published what is perhaps John Betjeman's finest

poem, the terrifying Song Of A Nightclub Proprietress. His seemingly bufferish production

anticipated many a 1960s vogue. The Saturday Book had Victoriana, art nouveau, Beardsley,

railway relics, vintage motor cars - and no sooner had he issued a volume about the east than

the Beatles flew off to meditate under an Indian guru.

Hadfield was born in Birmingham, the son of a solicitor, and educated at Bradfield College.

Declared unfit for war service because of TB, his 1930s publishing experience, at JM Dent and

elsewhere, led to his being sent by the British Council to the Middle East. En route, his ship

was torpedoed, and Hadfield sustained a watery wait for rescue by reciting poetry aloud.

After the war, he was a force behind the Festival of Britain and at the National Book League.

The success of Love On A Branch Line enabled Hadfield and his wife, Anna McMullen, to buy

Barham Manor, where he developed a taste for gardening. Perhaps it was the brush with TB

that made him take such delight in life, but it was not without sadness: Anna died in 1973, and

his son Jeremy, who worked for the publishers Macmillan, died in 1988. Soon after his wife's

death, the Saturday Book ended, a victim of production costs and the lacklustre phase through

which English publishing went in the 1970s.

Hadfield found renewed happiness in a second marriage, to Joy Westendarp.

John Charles Heywood Hadfield, writer and publisher,

born June 16 1907; died October 10 1999 - from ‘The Guardian’.

There were several other obituaries published which included those in US newspapers.

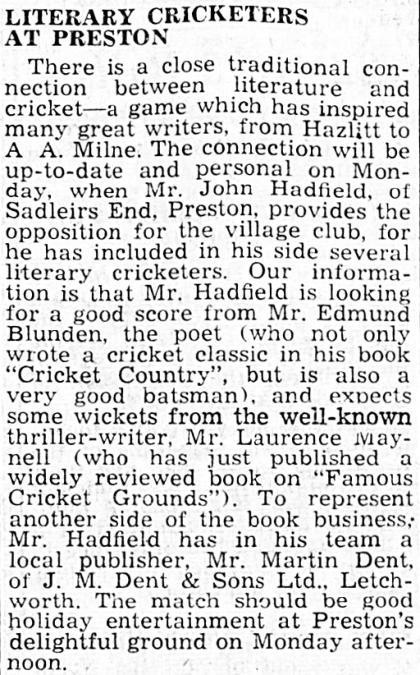

John was born on 12 June 1907 at Handsworth, a suburb in the north-west outskirts of Birmingham.

In 1911, his parents and an older brother were living with his maternal grandfather, a manufacturing

goldsmith, in the nineteen-roomed Hamstead Mount, Hamstead Hill, Handsworth. John’s father was a

solicitor.

While his family remained at Handsworth, in 1921 John was noted at the public school, Bradfield

College in Berkshire - ‘Thoroughly unpretentious yet with lots to boast about, Bradfield is a heavenly

place to learn and to grow.’ After graduation, in 1928, he joined the London publishing firm of

J. M. Dent, where his authors included Field Marshal Montgomery, for whom he edited a book on the

history of warfare.

On 27 June 1931, John married (Phyllis) Anna McMullen (born 14 April 1904) at St Peter and St John,

West Mercia, Essex:

It was Anna’s American family connections which created the news headlines, but for Hertfordshire

folk the more interesting family link was that her father, although a stockbroker and member of the

stock exchange, was born at Hertingfordbury, Herts and descended from the Hertford brewing

family of McMullens or ‘Macs’ as it was known. McMullens was founded at Hertford in 1827 and,

after decades of acquiring pubs, at the turn of the century it was the second largest brewery in the

county with 131 hostelries. At the time of writing, McMullens’ portfolio at Hitchin included the

Coopers Arms (Tilehouse Street, purchased 1887), the Orange Tree (Stevenage Road, 1902) and

the Millstream, Walsworth.

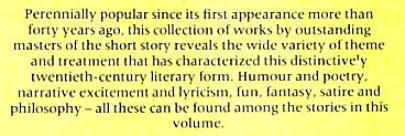

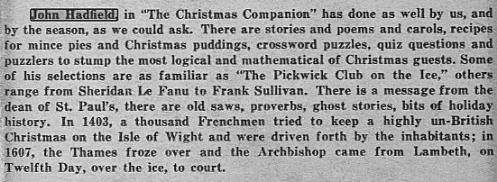

John hit his stride in 1939 with the publication of two more books which testified to his editing skills -

his Christmas Companion ran to almost 600 pages and was also published in the USA:

From the blurb, the reader will understand the gist of what John’s talents had produced and how, in his

early thirties, he was making a name for himself in the publishing world. On 23 September 1938, John

(5’ 10”, with brown hair, hazel eyes and fair complexion) and Anna left Southampton on board

SS Manhattan bound for New York. The couple were doubtlessly visiting Anna’s relatives while John

was perhaps opening new publishing doors.

A year later, the world was at war. John was unfit for war service because of TB and his publishing

experience led to his being sent by the British Council to the Middle East. His first unaccompanied visit

to Egypt was on the Empire Star which sailed from England on 18 October 1942. Now, Preston is

woven into our story because John then gave his address as Sadleirs End, Preston:

So it is that we can identify a small window of three years during which John and Anna moved to

Preston - it was between the taking of The Register on 29 September 1939 and 18 October 1942. A

comment by Anna in A Peacock on the Lawn fine-tunes our estimate of when the Hadfields arrived in

Preston: ‘We loved our Hertfordshire cottage, small though it was; and the yew hedge, which John

had planted in 1940 in defiance of Hitler, had reached perfection”.

Sadleirs End, Chequers Lane, Preston

As books officer for the British Council in Egypt, John formed a committee to translate English books

into Arabic. The translations varied wildly; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's ''Sign of Four'' became, in Arabic,

''Where Is the Treasure, O Sherlock Holmes?,'' while ''Gone With the Wind'' (a door-stop of a book,

running to around 1,000 pages) was whittled down to a mere 60 pages - a demonstration of ruthless

editing skills!

It was during another voyage to Egypt in the mid-1940s that his ship was hit by a torpedo and John

lost ‘his clothes, papers and a first edition of ‘Tristan Shandy’ (who readers will recall was modelled on

Captain Hinde of Preston Castle) and very nearly his life…(as he) drifted for three days in an open

boat before being rescued’. He is said to have whiled away his wait for rescue by reciting poetry

aloud. There is some evidence that John didn’t recover quickly from this experience. Writing the

foreword of a book in 1976 he confided that, ‘some thirty years ago I fell sick with a treacherous

illness which forced me to pass many months in bodily inactivity…my illness stirred up a host of

practical anxieties about my means of livelihood’. Whatever happened then, John was sent to a

sanatorium in Norfolk to recover from his experiences.

Possibly John needed some ‘time out’ for recuperation, reflection, to resolve his anxieties about his

means of livelihood and/or the necessity of finding work in peace-time. Piecing together the available

evidence, from 1944 he had been closely involved with the National Book League (NBL), which was

formed to provide common ground for those who valued books. He had an office in London (likely at

Abermarle Street) where he spent his working week in the 1950s. In October 1947, he, as director of

the NBL, addressed a meeting at Chelmsford when perhaps significantly he remarked, ‘The essential

ammunition for anyone who wants to use his brain is books. Our brains are practically all that is left to

us from the war’.

Gradually his literary output began to increase. He wrote two short articles for the Saturday Book

(which was an annual miscellany of assorted items): a history of the toby jug (1949) and An artist in

Glass - the engravings of Lawrence Whistler (1950).

Around this time, he also established the Cupid Press and published two ‘beautifully-bound’ books

from Preston in 1949 and 1950 - Georgian Love Songs and Restoration Love Songs. They were set

at Temple Press, Letchworth, Herts. These four pieces were clearly for a rather niche market.

He also earned a crust writing book reviews for The Sunday Times in 1950.

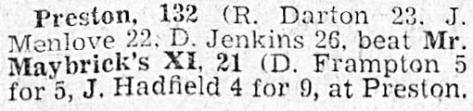

The following news reports provide an impression of his activities around Preston and in London

during the early 1950s:

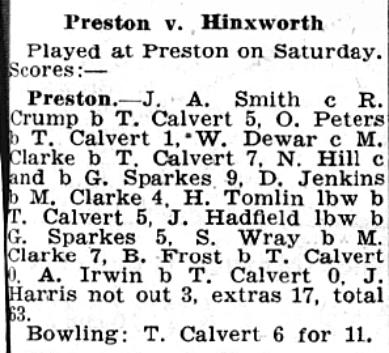

^ 3 March 1951

> At Letchworth’s Festival Book Week in

September 1951. Note that John’s

publisher, J M Dent, was at Letchworth and

that there was a display of book binding

leathers by G W Russell who was to

provide the leather for Mrs Maybrick’s WI

‘History of Preston’.

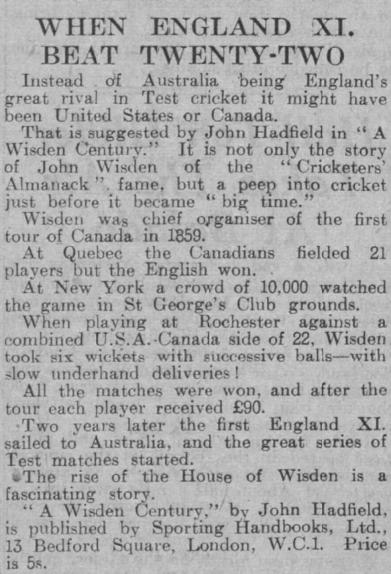

In 1950, John published a book about the life of cricket-giant, John Wisden, which received mixed

reviews:

With this reference to John’s cricketing opus, as we are approaching the time when the Hadfield’s left

Preston, it is appropriate to focus now on John’s notable contribution to Preston’s Cricket Club.

Preston’s cricket captain, Cyril Hilder declared that ‘the cricket club was revived by Mr John Hadfield

after the last war’. Frost’s History of Preston Cricket Club relates that, ‘John Hadfield 'press-ganged'

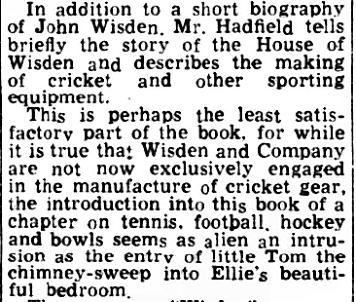

his friends and fellow cricketers to restart the club in 1947’. John was a right-handed batsman and

‘captained the side until he left the district. He was a vice president of the cricket club’.

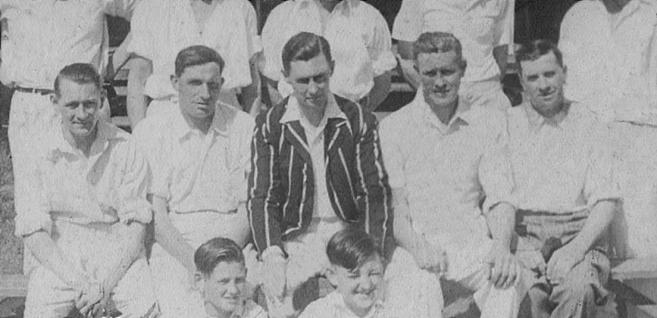

Harold Tomlin, John Hadfield, Sam Wray (my father) and Charlie Darton.

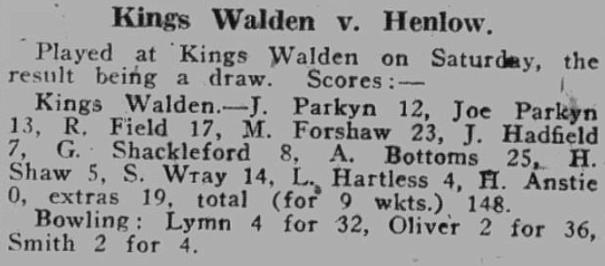

John and Sam also played cricket for Kings Walden in 1941 (see footnote)

16 June 1951

1 September 1951

4 August 1951

Before we leave John and his connection to Preston cricket, we

should mention his first novel, Love on a Branch Line, which was

published in 1959 after thirty years of publishing other people’s work.

It might be said that much of this novel has its roots in Preston

cricket. This is what its fly-leaf said:

In his mind’s eye, might John have conjured a picture of Dad bowling when he wrote that paragraph?

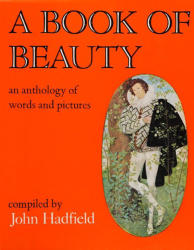

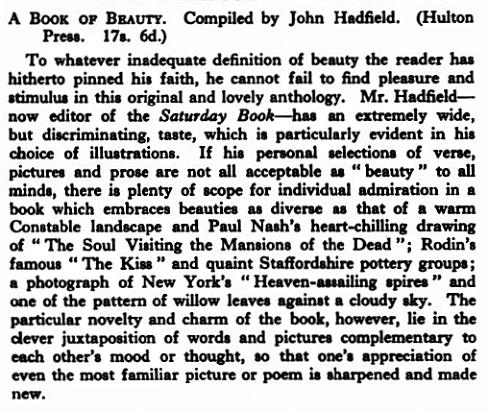

1952 was a turning point in John’s career as he firstly published the critically-acclaimed and

‘immediate best seller’, A Book of Beauty, and also became the second, and final, editor of the annual

miscellany, The Saturday Book. This success probably created the circumstances that allowed for the

Hadfield’s move from Preston.

Allow me an indulgent moment of whimsy. The novel abounds in descriptions of cricket matches. From

the two photographs shown, John knew my father, Sam Wray, literally rubbing shoulders with him. Dad

was an opening slow bowler. In his novel, John describes the dismissal of a batsman:

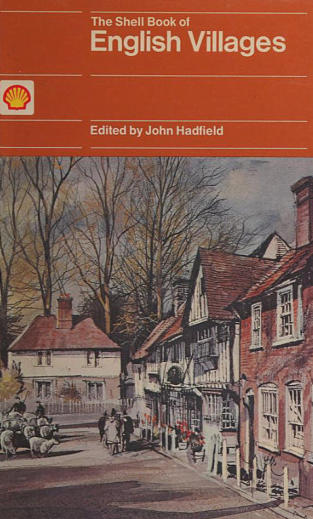

John’s second opportunity came when he was appointed as editor of The Saturday Book. This had

been announced in November 1951:

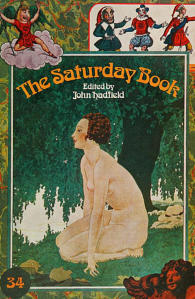

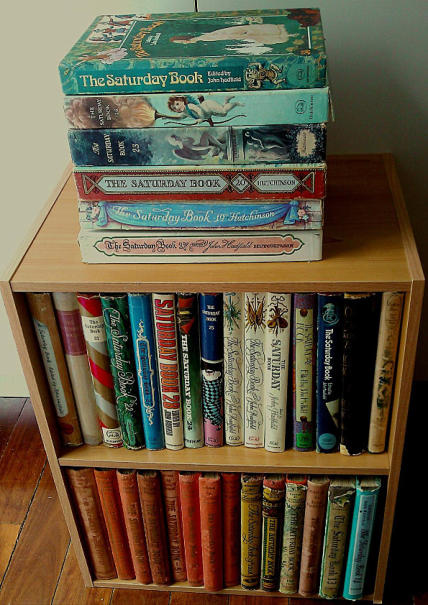

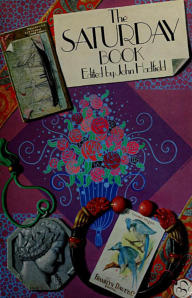

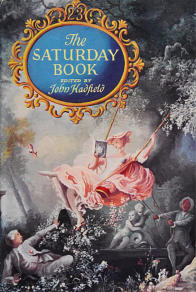

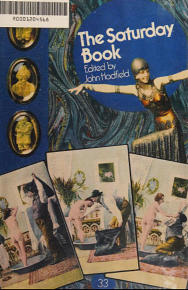

The Saturday Book was a collection of pieces of writing, essays and poetry, on a range of subjects

such as art, ballet, music and curiosities, written by different authors. These included John Betjeman,

Graham Greene, John Masefield, H. J. Massingham, George Orwell, J. B. Priestley, Siegfried

Sassoon, Evelyn Waugh, Jilly Cooper and P. G. Wodehouse. The book was published annually

between 1941 and 1975 - a total of thirty-four volumes (thirty-three are shown below) - and was often

advertised as an ideal Xmas gift to please every taste. It was for lovers of by-gone ages and was

illustrated with photographs and line drawings. Some of its content might be considered to be risque.

John’s gift as editor was to cajole and persuade contributors, surround himself with a team of

photographers, artists and lay-out experts, and know what his readers would appreciate and buy.

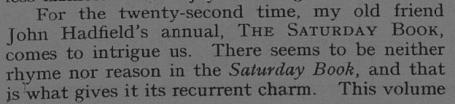

The newspaper cuttings assembled above provide some insight into how the Saturday Book was

enjoyed by even the hardened reviewer.

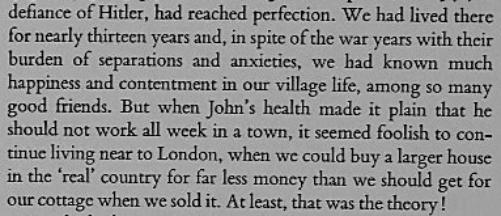

Their Preston cottage was proving to be too small for the needs of John and Anna, who confessed:

She elaborated that, ‘We were cramped in the cottage and now that John had to earn our living by his

pen and his wits, he had to have a proper room to work in…….John and I had been unavailingly

hunting for the ‘perfect house’ for some time…(if we) don’t get that house (Barham Manor, Suffolk) we

will settle down in our cottage and perhaps build on to it’.

They bought the manor house in the late summer of 1952, but moved in November, ‘staying with

various kind friends for some weeks’ (in Preston?). They ‘often went back to Hertfordshire to visit

friends’.

Ensconced in their new home, Anna wrote:

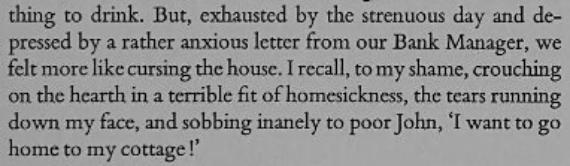

Before drawing a line under John’s successful life as a publisher and writer, a letter to him by Noel

Coward (who was the subject of one of John’s edited tomes) illustrates his talent, and how he was

viewed by his peers:

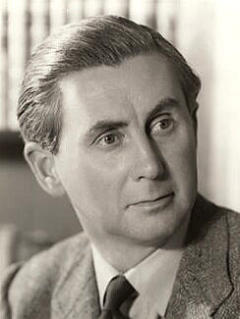

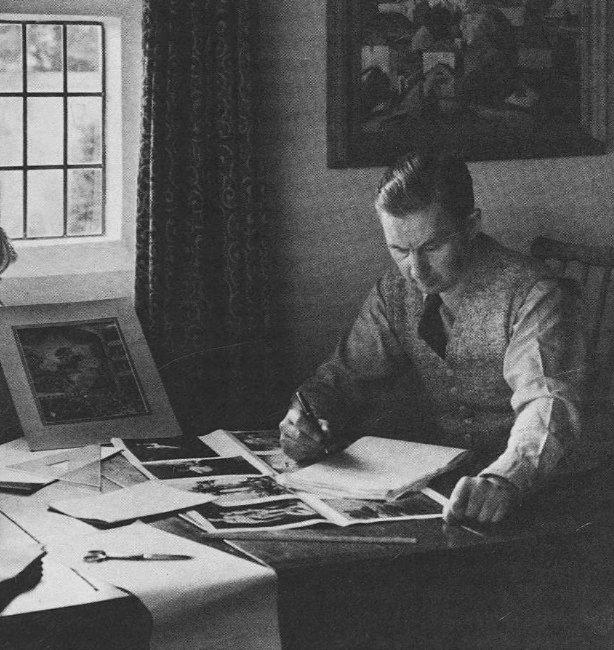

John and Anna at one of their Suffolk homes

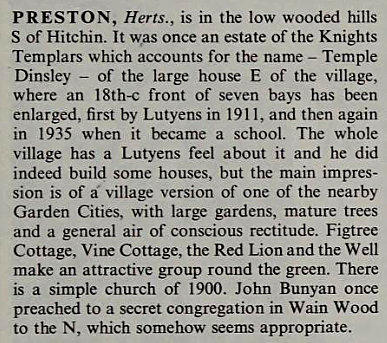

Finally, and aptly, I draw the reader’s attention to an entry in the one book of John’s that I have seen

before:

(Left) John and Anna (far right) in 1958.

(Above) Although John remarried after

Anna’s death in 1973, the two were

buried at St Mary and St Peter, Barham,

Suffolk.

John and Anna had a son, Jeremy H Hadfield, who was born in early

1932 at Amersham, Berks. He married Edna Segal in 1956 and the

couple had two sons. It appears that John’s family settled at

Amersham as Orchard End, Prestwood, Amersham (right) was his

address in 1939 when his sister, Cissie, was with the couple.

Now a brief word about John’s publishing activities. His main

penchant for many years was collecting together short essays and

pieces with a common theme and publishing them as books of

anthologies. He began to make a name for himself in 1936 when his

name was first featured in newspaper book reviews:

‘He bowled….

Footnote: John and my father, Sam Wray, turned out for Kings Walden cricket team in July 1941:

Preston cricket team in 1947 - left to right: Ron Whitby, Sam Wray,

John Hadfield, Charlie Darton and ‘Jockey’ Peters

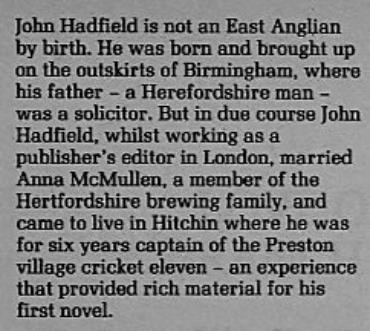

18 August 1950

Bookseller, a weekly periodical, published an obituary to John in November 1999: