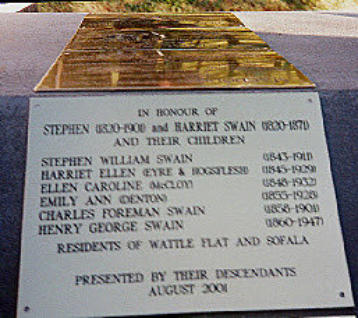

Stephen Swain: 1820 - 1901

I am a third generation Australian (writes Tony Swain).

When I grew up in a Central Western town in New South Wales (NSW), which was about 250 km

from Sydney, it did not occur to me there was a big world out there that was the source of my family. I

knew that my father, William, was born in about 1884 and had a twin, Charles, who did not survive

infancy. My grandfather was Harry, an old man with a white beard who was born on the goldfields.

My search for my ancestors began about thirty years ago. The speed of getting information was like

sailing by boat from England compared with the present accessibility of the internet. I also found that

people did not discuss their family history. This reluctance made my task more difficult.

I had learnt in school that Captain Cook discovered and claimed the Great South Land (Australia) for

England in 1770. Also, that American Independence in 1783 prohibited the shipment of convicts to the

former colony. But I was vague about Captain Arthur Phillip being commissioned in 1787 to establish

a penal colony in New South Wales and about the overcrowding of the British prisons and rotting

hulks in the estuaries. We were told of the First Fleet he commanded that anchored in Sydney on 26

January 1788 with 1,030 people, 736 of which were convicts. In all, between 1788 and 1868,

162,000 convicts were transported to Australia. Later research showed these were mostly not petty

criminals but hard-core offenders and some political activists.

My starting point was my Grandfather, Henry George Swain’s birth certificate. From this, I discovered

that he was born in 1860 amid the goldfields at Sofala, NSW and that his parents were Stephen and

Harriet Swain. From Stephen’s death certificate I learnt that he was born in Herefordshire (see later);

that for thirty-eight years he had lived in New South Wales (but not continuously) and that formerly he

had been a hotel keeper. I also knew the names of his living children and that his father’s name John

Swain.

I wondered: was Stephen a convict who was sent out from England? If not, why travel to the other

side of the world? Were there problems at home?

Obtaining information was difficult due to an unwillingness to talk about a possible convict ancestry.

Later, the information that Stephen was born in Herefordshire was found to be erroneous. Lengthy

research proved that he was born in Hertfordshire and that his father’s name was Charles, not John.

Stephen’s father, Charles Swain

I later discovered that Charles Swain lived from 1790 to 1837 in Preston, Hertfordshire. He was

described as a horse breaker, wheelwright and victualler, but never as a soldier. On 27 July 1808 at

Northampton, he joined the Nineteenth Dragoons and signed for a ‘limited period of service’. He was

described as 5 feet 7 inches tall; colouring – fair; eyes – hazel; brown hair; round face. (This could

also describe me when I was eighteen)

In 1809 the Regiment embarked for Ireland and by 1810 it was in Philipstown and Longford. In 1811,

Charles married Catherine Young, a Hertfordshire girl, at Temple Michael, Longford. A pregnant

Catherine returned to Bedfordshire and gave birth to Priscilla Swain on 16 October 1812 at Stopsley.

Her daughter was named after Charles’ youngest sister.

On 4 April 1813, the Regiment left for Quebec, Canada and arriving on 18 May. Charles Swain was

discharged at Romford on 9 Oct 1817 when his period of service expired. He then returned to his

home of Preston. He and Catherine had nine more children: Charles (1818 -1881), Stephen (1820 -

1901), Jonathan (1822 - 1911), Charlotte (1823 -1830), Frederick (1824 -1830), Caroline (1826 -

1902), Ann Marie (1828 -1901), Harriet (1830 -?) and Henry (1831-1831). The Swain family had a

history of keeping other public houses in the area - including Stephen’s mother, Catherine; sister,

Caroline; brother Charles and grandmother, Ann.

Charles’ father was the one-legged Stephen Swain (1755-1835). His sister was Harriet (1784-1847)

who married Joseph Sanderson (1769-1829). The 1851 census for Preston recorded Swains,

Sandersons and Joiners in and around Preston Green and Langley Bottom.

Stephen’s marriage and emigration to Australia

The 1841 England census noted Stephen Swain as living in Reading, Berks., born outside the county

and an apprentice. We don’t know what kind of apprenticeship he served nor why he was moved

away from Preston and Hitchin. The census also recorded Harriet Underwood/Ottaway, as a servant

girl aged 20 near Reading (probably this is how he and Harriet met). Caroline Harley (Harriet’s step-

sister) was living at Marylebone.

Stephen married Harriet Ottaway at the parish church of St Marylebone, Middlesex on 30 July 1841.

(Harriet’s mother married three times: to Underwood, Harley and Ottaway.)

I was also able to trace Stephens’ immigration details. They showed that he arrived in Australia

aboard the Duke of Roxburgh on 10 June 1842 with Harriet. So, the couple sailed from England a few

months after the wedding. Both were servants bonded to the first Mayor of Sydney, Stephen as a

coachman and Harriet as a kitchen-maid.

These were the details on the immigration papers of Stephen, Harriet and Stephen’s sister-in-law,

Caroline Harley, who accompanied them

1) Stephen Swain. Native of Hitchin, Hertfordshire. Parents Charles and Catherine,

mother alive. Farm labourer, age 22. No person certifying baptism. Character,

certified by John Cook of Hill End Farm and Wm. Curling of Hitchin. State of bodily

health certified by John Foster, Hitchin. Episcopalian. Reads and writes . No

complaints. Bounty £38.

2) Stephen’s wife: Swain, Harriet. Parents Daniel and Mary Underwood , Surrey.

Kitchen maid age 23. No baptism, character same as husband's. Reads and writes ,

Episcopalian, no complaints No children.

3) Caroline Harley, Stephen’s sister-in-law under his protection, Native of Bagshot,

age 19, housemaid

Comparing Stephen’s new home in New South Wales with his home in Hertfordshire, a census of

Hitchin parish in 1821 counted a population of 3,809 with 260 at Preston. Ten years later, Hitchin’s

numbers had increased to 5,211 and when Stephen arrived in NSW in 1842, Hitchin had 6,200

inhabitants. The population of New South Wales then was 30,000

Stephen and the gold rush in California and New South Wales

There was a depression in the NSW colony in 1843. The Mayor became insolvent and Stephen

became unemployed. He began his venture into private enterprise as a carrier. Then, in 1848, gold

was discovered in California. News of this reached Sydney in early 1849. Early family letters

mentioned that he was a ‘forty-niner’ and went to California with goods and provisions for the miners.

Thus, the note on Stephen’s death certificate (that he did not live continuously in NSW) was

explained. His ship was battered by storms near California and he lost some cargo. He had left his

wife and children Stephen William (born 1843), Harriet Ellen (1845) and Ellen Caroline (1848) in an

inn/hotel in Sydney. (This has since demolished and replaced by a newer hotel - the side street being

known as Swain Street.)

Stephen was away for eighteen months and oral history relates that he was shipwrecked on the

return journey. The vessel was feared lost and Harriet believed she was left alone with her children.

When he did return, Stephen was greeted as ‘the man with the long beard’. His return to Sydney

coincided with the fever of the first Australian gold discoveries in the Blue Mountains to the west of

Sydney at Ophir and Sofala in 1852. This find caused feverish movement of people to NSW, including

convicts and free settlers, and triggered a rush of immigrants from Britain, Europe and Asia.

Stephen and Harriet at Sofala, New South Wales

Stephen learnt in America that that mining was a risky

venture and he became a carrier of provisions for the

miners and the diggings at Bathurst (the first depot/town

about 200 km west over the Blue Mountains). He also

established an inn, beer and billiard hall at Wattle Flat

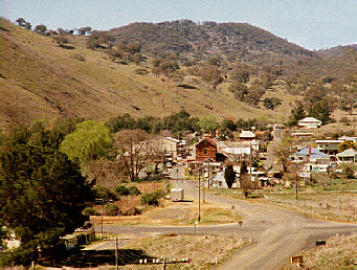

which is situated at the top of an escarpment before the

descent to the Turon River and Sofala (shown right).

Later, he moved to Sofala and opened a hotel known as

The Oddfellows’ Hotel. When Stephen was involved with

these hotels he was drawing on the experience he had

witnessed in his youth.

At Sofala, Stephen and Harriet had three more children: Emily Ann (born 1856), Charles (born 1858)

and Henry George (born 1860). In local papers, he was later described as ‘a most dependable man,

and drove a splendid team of horses’. A commemorative book of the district describes Harriet in

this way: ‘.... Mrs Swain was another splendid woman for a pub. She was a Surrey woman, if I am not

mistaken; from down Farnborough way and as jolly hearty a woman as one could wish to see at the

head of a dinner table. She was a splendid cook and had a large heart. Thus it often happened,

sometimes after midnight that a snack would be suggested and out would come a ham, a pair of cold

fowls or duck or some salmon, and all hands would set upon the table and fortify themselves with

solids in order for another onslaught on the fluids! Brandy, hot rum and port wine were the tipples of

those days and plenty of them - --- At these midnight refreshers it was customary to ask Mrs Swain to

sing The Little Oyster Girl which she always did in fine style without much asking’.

Stephen prospered in Sofala but Harriet died on the 15 April 1871 and is buried there.

Towards the end of the 1880s, Stephen retired to Sydney surrounded by the nearby homes of his

daughters and their families. Of his three sons, he helped to establish the eldest and youngest in

business. The Peak Hill districts was the site of another gold strike in this period of the late 1880s and

his eldest son, Stephen William (1843-1911), left Sofala and started another Hotel in Peak Hill. This

became the premier establishment of the district.

His son, William Henry, at the age of seventeen began what has become an iconic

Australian merino sheep stud. Charles Swain (1858-1900) went to Tamworth and

was an apprentice trimmer in the motor industry. He later inherited a Sydney house.

He died of typhoid before his father. Lastly, Henry George (1860-1947) settled in

Orange and owned rural property, orchards, as well as slaughtering and butcher

shops. He is my grandfather, Harry (shown right). Stephen’s three daughters each

inherited a Sydney house and a shop in an upmarket suburb.

Stephen died at the home of his daughter, Ellen Caroline McCloy and her husband, William, at 181

Hargraves Street, Paddington on 15 April 1901. This was thirty years to the day after the death of his

wife Harriet. He is buried in Waverley Cemetery with a fine position overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

As to why Stephen and Harriet left England, we still don’t know. Perhaps the stories told by his father

(who had been to Canada with the Nineteenth Dragoons) encouraged him to look further afield than

England. Did he serve an apprenticeship as a coachman in England - he seemed to have good

sponsors for his migration?

Did he have any contact with his Preston family after leaving England? From oral history there was

an account that Emily Soldene, an opera singer, was a relative. The full story of Emily was published

in 2007: Emily Soldene, In Search of a Singer by Kurt Ganzl . From this, we find that she was the

daughter of Priscilla Swain (1812 -1900) who was Stephen’s older sister. Emily and her troupe toured

Australia in the 1870s and 1880s, visiting Sydney. The 1841 English census records Priscilla and two-

year-old Emily at the same London address as Caroline Swain (1826 -1902), another sister. It was

from a descendent of Caroline that I have the only known photo of Stephen (shown top), taken in

Sydney, during the time that Emily was in Sydney. Emily lived in Sydney in the late 1890s when Uncle

Stephen was living there. But we have no indication of any contact between Stephen and Emily apart

from the photograph.

Stephen’s legacy to Australia

Stephen has been described in various documents and forums as; labourer, coachman, carrier, gold

miner/investor, hotel keeper, property owner and on his death certificate as gentleman.

But his real legacy was the wealth he accumulated by adventure, endeavour, hard work and luck.

He left an ethos which was supported by the ability to progress. To my knowledge his descendants all

fulfil the adage, ‘none are on drugs, none in prison, none unemployed and none in poverty.’ However,

they have made significant contributions to society. They have been involved in the fields of

architecture, armed services, environment, engineering, education, health, finance, agriculture, wool

industry, property development, security, aviation, local government, racing industry and hospitality.

Notable Swain descendents include:

- navigator for Sir Charles Kingsford Smith in Southern Cross flight from England to Australia.

- creator and builder of the Australian State Coach used in London since 1988 also the

nearly completed (and yet to be delivered) The Britannia Coach for Her Majesty.

- personal chef for international celebrities.

- discrete security company for Head of State and Papal visitors.

- premier merino sheep stud.

- horse breeder for Olympic equestrian gold medalist.

Henry (Harry) Swain’s five sons in 1919: Back row l to r; Francis (Frank), William (Billie, Tony

Swain’s father); Front row l to r; Edward (Ted), Albert (Bert) Henry Charles (Jack).

In 1999 a reunion in Orange at ‘the farm’ of some of the

descendants of the Orange and Peak Hill families to

celebrate Harry’s one hundred years at the farm, welcomed

260 people from Australia and New Zealand.

Since 1999 the full extent of the families of Stephen’s and

Harriet’s girls has been proved. I can confidently confirm

that, as of 2006, there are over four hundred families and

more than one thousand people who have descended from

Stephen and Harriet.

In the year 2008 I went home to Stephen’s Preston. I met

some cousins; drank at The Red Lion and walked the lanes

and pastures. It was a wonderful feeling.

(I am grateful to Tony Swain for his account and photographs and to Wendy Dinsdale for her

photograph of Stephen)