Morality

In this article, the sexual mores of Preston villagers in the nineteenth century are examined.

Even today, this sensitive subject may be embarrassing and frowned upon by many, especially older

ones. In my wife’s family, one relative, a staunch, elderly churchman, went to extreme lengths to

prove the legitimacy of his line – and chose to ignore other signs of immorality among his ancestors.

One cannot change the bald facts of life which involve our forebears, however untenable. Many family

histories have instances of pregnant brides and illegitimacy; indeed, were it not for the loose morals of

several of my paternal and maternal ancestors, I should never have been born. Who am I to sit in

judgement!

Two main topics have been researched: bridal pregnancy and illegitimacy (i.e. children born out of

wedlock). I have a non-salacious interest in this subject as, to put it bluntly, several of my family at

Preston were fornicators and I wondered how they would have been regarded by their neighbours.

Pregnant brides

How many of Preston’s brides were ‘infanticipating’ as they walked (or waddled) up the aisle of local

churches? It is a simple exercise to check when a couple married against the baptismal date of the

first child born to the newly-weds. These details can be found on this web-site. During the century

between 1800 and 1900, out of 117 brides who remained in Preston after their wedding, 36 were

pregnant (31%). This is unremarkable. The ratio conforms to the national average -‘in the first half of

the nineteenth century almost one-third of all brides were pregnant’.

Despite the warnings about the perils of fornication from the pulpits of the Anglican and Baptist

churches, there would appear to be a general acceptance among the labouring classes of Preston

that courting couples could be intimate before their nuptials or that, if an unmarried girl became

pregnant, her partner would ‘do the right thing’. Perhaps a local custom known as ‘bundling’ was

practised, which was a means of establishing whether a union would be fruitful by a trial marriage.

The couple, who left their marriage to the latest of last minutes in the century, were married at St

Mary’s, Hitchin on 9 December 1844 and christened their first child twenty-nine days later at Kings

Walden on 7 January 1845.

Illegitimacy

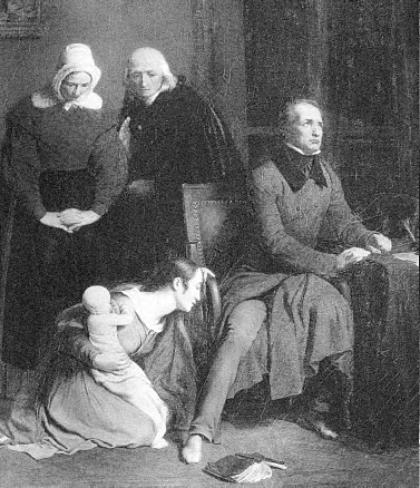

In the Church’s eyes, those children born out of wedlock were frowned upon. Illegitimacy has been

described as ‘an offence of the poor and the obscure’. Such progeny were often stigmatised in the

parish records by notes such as ‘base’, ‘bastard’, ‘byeblow’, ‘chanceling’, ‘mis-begotten’, ‘Child of

shame’, ‘whoreson’ and ‘lovebegot’. One author listed eighty-seven different words, English and Latin,

which were used to identify the fruits of fornication.

Because it was likely that a financial burden might be placed on the parish following the birth of a child

to a single woman, a Maintenance Order might be issued. The father was instructed to make a

payment to the overseers of the poor to offset the costs of confinement care of the infant, as

happened to Charles Swain of Preston. (Link: Maintenance) Sometimes a Bastardy Bond might be

arranged whereby the family of the father would agree to provide for an illegitimate child.

According to the baptismal records of Hitchin, Kings Walden and Ippollitts which include Preston

people, out of 859 baptisms, 34 were illegitimate (4%) – that is, no father is noted on the page. This is

slightly lower than the national average which was about 6% in the middle of the 1800s. Only two of

these children died in infancy. Although fewer children were baptised near the end of the nineteenth

century, there was a slight trend towards greater illegitimacy in later decades.

Perhaps the most extraordinary example of immorality at Preston concerned my great grandmother,

Mary Currell (nee Fairey). Her first child, my grandmother Emily, was born four years before her

marriage to Thomas Currell. The father was probably William Cox of Hitchin. When she and Thomas

married, they had four more children, however when the 1881 census was taken, the Thomas was no

longer living with the family.

Then, on 14 January 1883, Mary had two sons baptised. One, who was born towards the end of

1880, was fathered by her husband, Thomas. The second son was born in early 1882 (and therefore

conceived before the 1881 census) but the parish record describes Mary as a ‘single woman’. A

second illegitimate son was born in 1884 when Mary was forty-two. Possibly, she had an extramarital

affair in 1881 which prompted Thomas (not one to forgive and forget as shown by his behaviour when

he discovered the dying miller at the bottom of Preston Hill. Link: Miller) to pack his bags and leave.

With this flagrant parental example set before them, it is hardly surprising that Mary’s daughters, who

were aged nine and twelve in 1884 and so witnessed her behaviour with knowing eyes, should also

have illegitimate children. One of these was born at Brighton, which may show a desire to conceal the

birth from the prying eyes of villagers.

Earlier in the century, there was another similar example of a mother and her daughter having

illegitimate children. The family were living firstly in one of the cottages attached to Preston Hill Farm

and then at Kiln Wood. Both mother and daughter had three illegitimate children. In the mother’s

household in 1841, 1851 and 1861 there is a male lodger of a similar age and one wonders whether

they were in a common-law marriage.

Case studies

Conclusions

Because of the prevalence of premarital sex, especially among the labouring class, it is hard to

believe that pregnant brides would have been looked down upon by their peers - although in a small

village they might have been the butt of gossip and speculation. Possibly, immorality was less socially

acceptable as the rate was below the national average. It would have been difficult to hide an extra-

marital affair in such a tightly-knit community.