Mobility of Preston folk in the nineteenth century

When researching the mobility and movement of Preston villagers, a distinction should be made

between the ‘locals’ and newcomers. Included among the new arrivals were many of the farmers who

had no roots in the area, their transient farm servants and the tradesmen’s apprentices. Several of

these temporary residents suddenly appear at Preston in one census and vanish without trace ten

years later. I have therefore concentrated on people who were renting cottages around Preston when

looking at their movements.

Their ‘Country’

The historian David Hey in his book, Journeys in Family History states, ‘Although people were

strongly attached to their own parish, they also felt that they belonged to a wider, more loosely-

defined district which they thought of as their “country” - the neighbourhood that was bounded by the

nearest market towns.’

He then ‘reminds us that people had a sense of belonging to a neighbourhood in which they had

friends and relations who spoke like they did and who earned their living in the same familiar ways’.

He added that ordinary men and women married someone from their own ‘country’.

Much of this was true of Preston villagers in the nineteenth century. As we will see, most were born

either in Preston or within a five mile radius of the village and remained inside this area taking

marriage partners from the vicinity. When researching marriages of Preston folk, the same familiar

names of local families reoccur like old friends.

However, there was less of an attachment to their own parish here than is suggested, perhaps

because of the way in which the parish boundaries dissected Preston. Villagers (apparently with little

regard to parish loyalty) moved from and went to Kings Walden, Ippollitts, St Pauls Walden, Kimpton,

Offley and other nearby parishes.

The possible effect of straw plaiting on mobility

One of the obstacles to freedom of movement between parishes was the Poor Law arrangements

whereby newcomers to an area were discouraged if they posed a potential drain on local resources

because of illness, unemployment or poverty. The worst case scenario would be a single mother with

children moving into a parish, with all the implications for their future care. Probably, she would be

quickly dispatched or ‘removed’ to her settled parish by the overseers.

Because of the straw plaiting activities of old and young women and children in Hertfordshire, perhaps

there was less concern about the burden they might place on local finances. In Preston from 1851-

1901 only eleven people were described as ‘pauper’ or ‘receiving parish relief’. As a result movement

between parishes in Hertfordshire did not pose too many problems for the local parish overseers.

Walking to work

Another factor which should be considered when researching the mobility of Preston villagers is how

far the agricultural labourers were prepared to walk to the farms on which they worked. There are few

indicators of where they worked, but newspaper reports indicate that labourers did not necessarily live

near their work. For example, during a court case in 1882, Thomas Jeeves, who kept the Bull Inn at

Gosmore, produced an alibi that he was working at Temple Dinsley, about a mile away. Also, during a

court case in 1876, Charles Watson, a farm labourer who lived in Hitchin, was working for Mr Marriott

at Castle Farm, Preston, which was almost three miles from his home.

The arrival of the railway at Hitchin also pushed back frontiers of travel and mobility. In 1864, when

the robber of a dying man at the bottom of Preston Hill went on the run, he took the train from Hitchin

to Hatfield which is 14 miles away. In the 1890s, the children of Preston were able to enjoy two day

trips to the seaside. One was to Skegness which was 87 miles away.

Birth place of Preston villagers in 1841

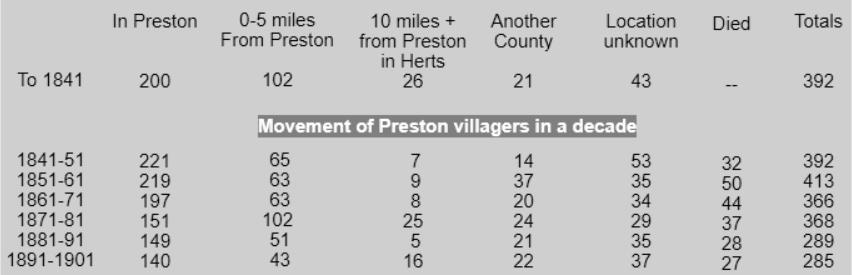

Using the 1841 census as a starting point, of the 392 local people living in Preston (excluding farmers

and their servants), exactly 200 (51%) were born in the village.

Furthermore, another 102 were born within 5 miles of the village, principally at Kings Walden - thus

more than three-quarters of Preston’s population were born within a five-mile radius of the village.

Between 1841 and 1901, from figures extracted from the censuses, 983 (52%) local people moved

out of Preston - but they didn’t move far. Of these, 387 (39%) relocated within five miles of the village

and a further 295 (30%) stayed within Hertfordshire. One hundred and three (10%) moved to the town

of Hitchin and approximately fifty moved to London..

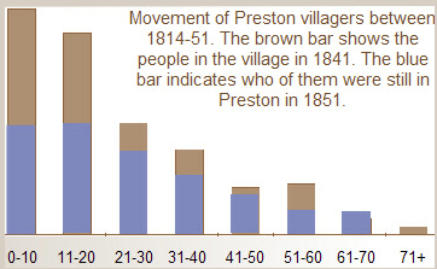

The graph on the right shows the ages of villagers

who moved out of Preston between 1841 and

1851. The brown bars are age groups in 1841 and

superimposed on them are the blue bars which

show the the age groups ten years on. The

difference (i.e. the amount of brown seen)

represents those who moved out of Preston during

this time.

This graph is typical of all the decades. It clearly

shows that the trend was for young families to

move. The young blood of the village was seeping

away - in common with many others, this ‘English village began to rot from the centre’.

Why did people leave Preston? It has been suggested that there was an understandable desire to

earn better wages than farm labourers could command - hence the shift to towns such as Hitchin,

Luton and London. While this was undoubtedly the case for a few villagers, the majority moved to

other parts of the countryside and continued as agricultural labourers.

Perhaps the two fundamental reasons for families leaving Preston were that firstly, the farms could

not provide the sheer volume of work for so many men and secondly (and even more basically), there

were just not enough houses in the villages in which young adults and children could live. The

censuses indicate that the number of homes in Preston decreased from 82 in 1851 to 64 in 1901.

Faced with no work or homes, young couples packed their belongings, arranged for the services of a

carter and left.

Where Preston villagers in 1841 were born

Movement of Preston villagers in a decade