Preston people: Elizabeth Phillips - Preston’s first midwife

This article has been in the in-tray for several months - reserved because despite

considerable research and an e-mail correspondence, I didn’t know the full identity of this

lady.

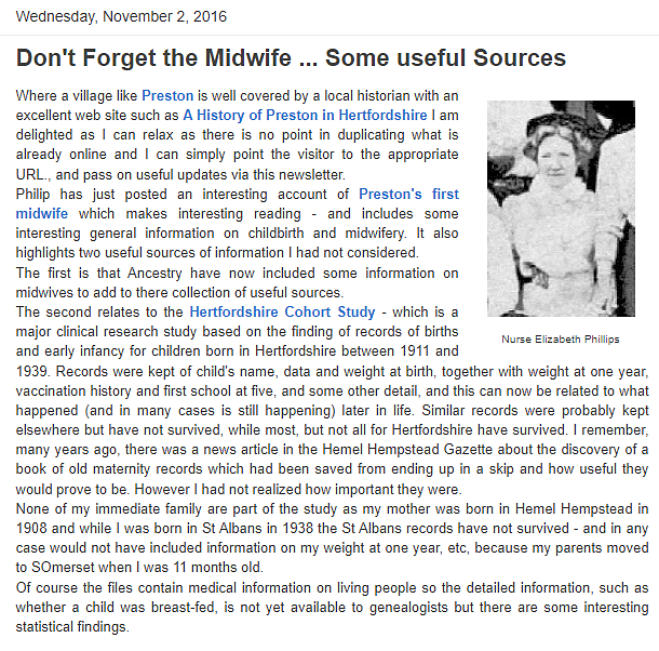

I knew her last name (Phillips) and that she served the village community from January

1911 until the end of 1915. There was also a photograph of her in Mrs Maybrick’s

Scrapbook (shown above) but that was the sum total of what was known.

Then, in September 2016, the web-site, Ancestry.co.uk, released details of British historical

midwives and many of the blanks about Nurse Phillips’ life could be filled in - although her

origins are still a mystery......

A brief history of midwifery

Before the eighteenth century, women in labour were traditionally

attended by other women. These included friends and relatives with

experience or women who made it their profession. Women became

midwives through an ‘apprenticeship’ by attending labours,

particularly in the company of another midwife.

With no official system of regulation, midwives were normally self-

appointed, self-taught, and often illiterate. While they may have been

skilled at the normal delivery of healthy women, they had no training

for dealing alone with obstetric and paediatric complications. They

also had little education of any kind and so lacked theoretical

knowledge of even basic reproductive anatomy, physiology and

pathology.

As a result, the ‘profession’ was riddled with backward and dangerous practices. The view of the

“incompetent midwife” was popularised by Charles Dickens in Martin Chuzzlewit, wherein Sarah

Gamp (above) was lampooned as an alcoholic midwife, sick nurse and layer-out of the dead.

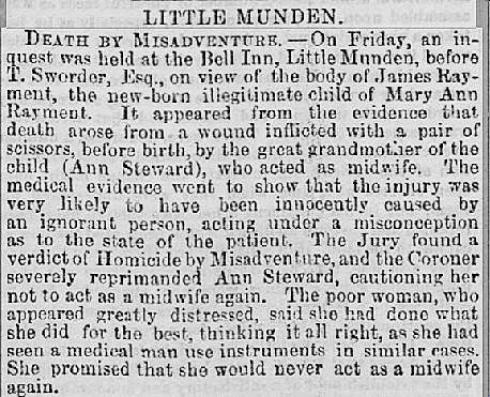

The Hertfordshire newspapers of the nineteenth century confirm this view of untrained midwives.

This account appeared in the Hertfordshire Express on 27 October 1855:

Haunted by high mortality rates of mothers and babies, this lack of regulation could not continue. The

Midwives Act of 1902 set up the Central Midwives Board (CMB) for England and Wales. This was

responsible for the regulation of the certification and examination of midwives, the regulation of the

practice of midwives and the appointment of examiners. The approved period of training was three

months and midwives were encouraged to keep a case book of all deliveries.

Women who possessed a recognised qualification in midwifery were automatically admitted to a Roll

of qualified midwives under the Act. Women of good character who had been in practice for at least

one year could also apply for admission to the Roll as ‘bona fide’ midwives. All other women intending

to become midwives had to take an examination in competence before a certificate was issued which

allowed them to practice. From April 1910, no person could habitually and for gain attend women in

childbirth, except under the direction of a doctor, unless she was certified under the Act.

The dangers for mother and baby during labour before 1902

The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachael - D Chiesura

Everyone, especially the expectant mother, was morbidly aware of the risks of childbirth. In the

seventeenth century, Joseph Hall, Bishop of Exeter, wrote ‘Death borders upon our birth and our

cradle stands in the grave’. Only recently has the giving thanks to God for, ‘The safe deliverance and

preservation from the great dangers of childbirth’ been removed from the Church of England prayer

book from the service for the ‘churching of women who had recently given birth’.

Although death rates from many other conditions were high, they at least were among people who

had been ill beforehand. Death in relation to childbirth was mostly in fit young women who had been

quite well before becoming pregnant. They died, often leaving the baby, and other children in the

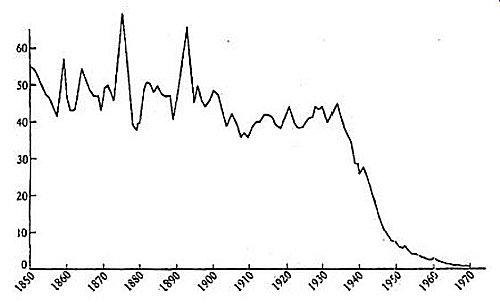

family from previous births, with a widowed husband. The graph below shows the annual death rate

per 1000 total births from maternal mortality in England and Wales (1850-1970)

The main causes of maternal mortality were puerperal pyrexia, haemorrhage, convulsions and illegal

abortion. Puerperal pyrexia was thought to be due to some vapours in the air which could be carried

mysteriously from one woman to another. It was only with extreme reluctance that the medical

profession accepted that such transmission could be by the birth attendants or as Alexander Gordon

wrote as early as 1790 ‘... it is a disagreeable fact that I, myself, was the means of carrying the

infection to a great number of women’. In America, Oliver Wedell-Holmes also avowed that ‘... the

disease known as puerperal fever is so far contagious as to be frequently carried from patient to

patient by physicians and nurses.’ Both men were vilified for holding and promulgating this view.

Puerperal pyrexia was caused by midwives and doctors and remained a common cause of death in

childbirth until the early part of the twentieth century. Infectious organisms on the hands of the birth

attendants were transferred to the woman’s uterus. The disease usually began on the third day after

delivery. Typical symptoms included high temperature; severe headache; raised pulse; severe

abdominal pain; vomiting and diarrhoea. Death occurs when the infection spreads, resulting in

peritonitis and septicaemia.

At Gosmore (near Preston) on 28 August 1862, Thomas Currell’s, first wife , Mary Ann (nee Watson)

died of ‘puerperal fever’ leaving him a widower with four small children.

Midwives and nurses at Preston before 1911

Information about the care of the sick, elderly and pregnant at Preston during the years leading to

1911 is sketchy. The Fenwicks and Brands of Temple Dinsley employed their own nurses and

nursemaids. Two local farmers with young families had a resident nursemaid. In 1901, Mary Ann Bell

(64) of Back Lane was recorded as a midwife and in that same year, Elizabeth Roberts of Sootfield

Green was noted as a ‘monthly nurse’ (who attended mothers after the birth of a child). In 1851, Sarah

Sharp (63) was described as a ‘nurse’. Between 1871 and 1891, my greatx2 grandmother, Susan

Currell (born 1802) served the local community as a midwife and monthly nurse. As the mother of

Thomas Currell, was she perhaps the carrier of the organism that carried off Thomas’ wife, Mary Ann?

In the absence of more local information, we fall back once again on the recollections of Edwin Grey

at nearby Harpenden (ten miles south-west of Preston) which likely mirrored the circumstances at

Preston in the late nineteenth century. He wrote, ‘I don’t remember in my young days that there were

any certified maternity nurses or qualified parish nurses in Harpenden....The people seemed to

depend in maternity cases upon the elder and more experienced of the married women just round

about (note the ages of the ‘midwives’ at Preston noted above)...several of the elder of the cottage

women were very clever and efficient midwives. They couldn’t stay, but would go to the cottage each

morning and night for some little time after the birth to attend to the mother and child, wash, change

and put them comfortable. At other times, neighbours would take turns to pop in. The fee charged by

these cottage midwives was five or six shillings, sometimes as low as 2/6d....now and again they got

nothing at all but a promise.

‘Parcels of linen (“baby parcels” or “bundles”) of clothes, sheets and counterpanes were loaned for a

month.’ In cases of sever illness when a watch was kept day and night, ‘some of the young women

and also some young men would volunteer to take on night duty in turn so that members of the family

could in turn take their rest. One woman watcher would be in the room with the patient. Another

watcher would see that the fire was kept going and a lot of hot water (was) always at hand. They

would also be in readiness to render any assistance if required. Also, about 3.00 am a cup of tea

would be prepared for her/himself and the watcher in the bedroom.’

When a contagious disease (such as smallpox) struck, the affected family kept to themselves as much

as possible and children were told not go play nearby. When a villager fell ill, a doctor was called or an

old experienced person would advise treatment. It was hard to isolate the patient in a small home with

few rooms and a large family. Whooping cough might be treated by inhaling sulphur at a gas house;

eating a fried mouse; making a sandwich from the sick person’s hair and giving it to a cat to eat – such

were the old wives’ remedies.

Villagers also put faith in homely medicines such as salts and senna, brimstone and treacle and also

the healing virtues of ‘yarbs’ (herbs). Stewed groundsel was used for poultices; marshmallow leaves,

for boils; lily leaves for cuts; dock leaves for galled feet; dandelion roots, for liver problems; ‘Yarb tea’,

for general health; old men carried small potatoes in their pockets to ward off rheumatism.

A picture of midwifery and maternal care in Hertfordshire around 1913

In 1911, Ethel Margaret Burnside (Hertfordshire’s first “chief health visitor and lady inspector of

midwives”) assembled a team of midwives and nurses charged with improving the health of children

in Hertfordshire.

A midwife attended women during childbirth and recorded the birth weight of their offspring on a card.

A health visitor subsequently went to each baby’s home throughout its infancy and recorded its

illnesses and vaccinations, development and method of infant feeding and weaning; the baby was

then weighed again at one year of age. This information was transcribed into ledgers at the

Hertfordshire county office. The ledgers cover all births in Hertfordshire from 1911 until the NHS was

formed in 1948. (We will return to these records later.)

Two years later, the Hertfordshire Express reported that from 1 Jan 1912 to 31 Dec 1912, 3,179 cases

were handled by midwives and monthly nurses (midwives: 2,491 ) (down sixty-seven on 1911; thirty-

five cases of twins) and 688, by doctors. The number of babies born alive was 3,081. Fifty-two died

before the tenth day and forty-three after the midwife had stopped attending. Medical aid was sought

on 276 occasions (11%), fifty-eight for the baby. In the county there were twelve maternal deaths

during 1912 which involved cases dealt with by midwives and monthly nurses, of which only four

were associated with midwives.

However, during 1916 in the Stevenage district, it was reported that ‘many villages had been without a

midwife’. Consequently, the local Government Board and Hertfordshire CC, together with subscribers,

formed an association of Stevenage, Graveley and Shephall to employ two nurses – one for all sick

nursing, health visiting schools and TB; to the other fell the duties of midwife and maternity nurse. In

cases of complications, they were to call in a doctor.

Preston’s first midwife/nurse

With a fanfare, in January of 1911, the St Mary’s, Hitchin Parish News announced, “We all welcome

Nurse Phillips to Preston and trust that she will be happy in her work amongst us. Several cases of

illness have quickly shown how useful it is to have a resident nurse in the village. The generous terms

of securing this help should induce all to become subscribers”.

Some information is available about Nurse Phillips (1874 - 1947). Her full name was Elizabeth Phillips

and she was born on Boxing Day, 1874 - making her thirty-seven years of age when she arrived at

Preston. Her origins are undiscoverable, although an educated guess is that she was Welsh - the

majority of females born with that name around that date were Welsh - and Elizabeth later lived and

died in Pembrokeshire, Wales.

Elizabeth qualified as a midwife on 7 April 1909 and the following year she was a resident at the

Royal Nursing Association, London Road, Derby.

She was appointed as Preston’s first local nurse being on-hand to minister to the needs of villagers

who stumped up the necessary subscription. These were as follows:-cottagers, 2/6d per annum,

(included mother and father and children up to fourteen years of age). Children over fourteen years

of age, 1/3d pa, until the age of twenty-one. Young men and women at home earning wages, over

twenty-one years of age, 2/6d. Farmers not less than 5/- pa.

The arrangements also stipulated that non-subscribers could have the attendance of the nurse for 3d.

per visit, but if the nurse being required by two persons at once, the annual subscriber had the first

turn. Confinement cases were 2/6d extra to annual subscribers of 2/6. If the nurse was required to

live in the cottage, the charge was 2/6d for the first ten days and 1/3d per week afterwards for a

month. The Nurse had to be withdrawn at the end of the month.

Visits by the nurse were made after contacting the secretary, Mrs N. Dawson, Temple Dinsley,

Preston. In the case of sudden emergency, when there is not time to obtain leave from the Secretary,

the nurse may be applied to direct, but notice must be given to the Secretary immediately. If the nurse

was required for a confinement case, at least two months’ notice was given to the Secretary.. The

nurse was not to be given a gratuity, beer or spirits. On visiting a house, the nurse would to make the

patient and family as comfortable as possible, doing any light work.

Nurse Phillips at Preston 1/1/1911 - 31/12/1915

Something of Nurse Phillips activities in the village as health visitor and midwife can be gleaned from

relevant entries in the school logbook (which noted outbreaks of epidemics) that follow and the known

births at Preston during this period.

12 October 1911 ‘Two children from Offley Holes are down with diphtheria’. The school was closed on

Friday afternoon and desks thoroughly scrubbed. 23 October 1911 ‘The two little Barretts are still

away and no fresh cases have broken out.’ (They were still noted as absent on 9 January 1912)

In September 1912 there was an outbreak of whooping cough and on 23 September only 47 children

attended the school as a result. This was followed by an outbreak of measles. The school was closed

on 4 November and after an abortive attempt to re-open on 2 December, school was next convened

for the new term on 7 January 1913.

On 19 May 1914, there was a note that three children were sent home ‘as they smell very badly. The

village nurse has been to see the mother.’ The following morning all were back in school – ‘they are

clean now, having had a change of clothing and a good washing’.

On 19 February 1915 Dr Day instructed that the school be closed until 8 March 1915 owing to an

epidemic of influenza.

When the autumn school term began on 31 August 1915, only thirty-four attended out of fifty-seven

due to an outbreak of impetigo.

In February, 1914, the St Mary’s, Hitchin newsletter commented, ‘Several instances of the valuable

work done by the Parish Nurse in Preston and Langley have recently come to our notice; and we take

this opportunity of expressing appreciation of the fact.

We are glad to know that so many of our parishioners are subscribers. It sometimes happens that

times of sickness come to those who have not joined, and so have no right to the service of the nurse.

Surely when a very small yearly payment is asked for, it is not too much to hope that everyone should

see to it that they become members and can call in the devoted attention of Nurse Phillips in the hour

of need.’

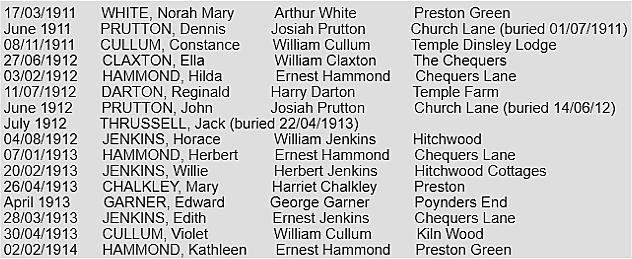

Next are listed children (16) born at Preston between 01/01/1911 and 31/12/1915. These include

children who attended Preston School and those who died in infancy and who were buried at St

Martin’s. It is impossible to identify those children who were born at Preston but whose parents

moved away before they went to school.

(Note: There is a significant gap in this list of births to Preston folk between 2 February 1914 and 31

December 1915. For much of this time, Britain was at war and many of the village’s young men were

embroiled in the conflict. Also, there was considerable migration into and out of Preston during this

time of uncertainty)

According to the ledger records, there were sixteen births recorded at Preston addresses between

1913 and 1916. Eight (seven boys and one girl) of these were delivered by Nurse Phillips. The

remainder, by Doctors Charles Grellet (born 1842), James Gilbertson (born 1860) and Barnes who

were based at Hitchin

Nurse Phillips leaves Preston - 31 December 1915

In January 1916, the St Mary’s, Hitchin newsletter noted, ‘The two hamlets of Preston and Langley

are very sorry to lose Nurse Phillips, who is leaving the district about the middle of this month. When

the Nurse came, people asked “What is there for her to do? Now she is going, the question is “What

are we going to do without her?” Nurse Phillips has unfailingly done her best. She was at the beck

and call of all, and night or day she rose to that call. We wish her every good wish, and long will she

remain in our memory.’

The following month a letter of thanks from Nurse Phillips was published: ‘To the Parishioners of

Preston and Langley. I take this opportunity of thanking you all for the very handsome gifts given to

me, and for the many kindnesses shown to me while I have been here. I will carry away with me not

only your lovely gifts, but also memories of four very happy years.

I hope you will make the path of my successor as smooth as you have made mine. Wherever my

work may take me my thoughts will still go back to the grateful patients and kind friends of Preston

and Langley. Again thanking you all, and wishing you all good-bye. Yours faithfully, E. PHILLIPS.’

So where did Elizabeth go? She is still noted as being at Preston in the CMB records of 1920 -

though clearly she had left four years earlier. From her letter, she planned to continue working as a

nurse. Perhaps her move was related to some war-time work.

A tentative note was made about Nurse Phillip’s replacement, ‘With regard to the nurse for Preston

and Langley, Mrs. Dawson asks us to announce that an arrangement has been made for the present

for Nurse Cummins, who has just taken up her residence at the Kings’ Walden Nurses’ House, to

undertake duty also in Preston.’ However, one wonders if this arrangement ever got off the ground -

Mary Cummins is not listed as a midwife at Kings Walden or Preston and she is not mentioned in

any documents relating to Preston.

Nurse Phillips between 1926 - 1947

Elizabeth is next found at Hook, Treffgarne in Pembrokeshire from 1926 until 1935, when she was sixty

years old. The 1939 Register describes her as single, a retired District Nurse and living alone at Mantawel,

Haverfordwest Road, Ambleston, Pembrokeshire (shown below) which was near Treffgarne and about

three miles east of the A40 which links Fishguard and Haverfordwest..

She was still living there when she passed away on 24 February 1947 - though the place of death was

Myrtle Cottage Ambleston. Elizabeth’s estate was valued at £1,354 and was administered by the farmer,

John Phillips and James Philips, who was a lorry driver.

Another CMB-qualified midwife living at Preston

This article cannot be left without mentioning another qualified midwife who lived at Preston, Florrie

Sugden. She qualified on 24 May 1930 and worked from that time until at least 1951 at Foxholes

Emergency Maternity Home, Hitchin. In 1938, she expressed at intention to practice at Norwich and

gave her address as 58 Unthank Road. Florrie was my aunt - Flossie (nee Wray) as we knew her -

who lived with her parents and her sister Nan at 5 Chequers Cottages..

This information is of interest to the writer as Flossie returned to Preston after a failed marriage in

Pakistan/Waziristan. She does not figure in the register of Preston electors raised in 1929 - a fact I

have wondered about. Perhaps these two pieces of information indicate that Aunt Flossie came back

to the village in around 1930.

A little-known research resource re: those born in Hertfordshire 1911 - 1948

Earlier I wrote that information about births in Hertfordshire ’was transcribed into ledgers at the

Hertfordshire county office’. The ledgers cover all births in Hertfordshire from 1911 until the NHS was

formed in 1948.

As part of a nationwide search of archives, staff working at the MRC Unit, University of Southampton,

discovered the Hertfordshire ledgers. The ledgers were computerised and linked to mortality records

using the National Health Service Central Register (NHSCR). In the early 1990’s, surviving men and

women who were born between 1920 and 1930 and still resident in Hertfordshire were contacted

through their General Practitioner and those who were willing underwent detailed physiological

investigations to explore life-course influences on adult disease. 717 men and women resident in North

Hertfordshire attended home interviews and clinics where a wide range of markers of ageing were

characterised. These clinics comprised the first follow-up of the Hertfordshire Ageing Study (HAS)

which was the first to demonstrate that size in early life is associated with markers of ageing in older

people.

The important aspect of this is that there appears to be a comprehensive record of births and early

childcare of Hertfordshire people over thirty-seven years which has remarkable details for the family

historian. That’s the good news. The bad news is that the ‘100-year’ rule probably applies to the

dissemination of this information - and only those related to the person born may have access to the

data.

More about this can be read at (Link) Hertfordshire Birth details

Chris Reynolds of the Hertfordshire Genealogy web-site has kindly added the following comments

about this article: