My job by Mary Turl

Some background information about Mary: She married (Elton) Gordon Turl during late 1941 in

the Thornbury, Bristol area. The couple then lived at Sharpness in Gloucestershire, but they had

moved to the Hitchin district by 1947. There, between 1947 and 1957, four children were born,

(Elton) John, Anne, Erica and Chris(topher).

In the spring of 1958, the family moved to Windrush, Back Lane, Preston. On 24 April 1958, the

three eldest children began attending Preston School. Chris was a pupil at the local school from

April 1962. John left Preston to study Physics at Oriel College, Oxford. Anne moved to London in

1968. Erica first left to study English at London University in 1970, but then changed course and

attended the Guildhall School of Music. Chris studied Electronics at Warwick University from

1975.

According to Mary’s account, she was Preston’s post-woman for more than fifteen years from the

mid-1960s until 1980. Meanwhile, Gordon was a vice president of Preston Cricket Club

Following a heart attack, in 1977 Mary’s mother (‘Nan’) moved from Hitchin to Windrush to be

with her daughter and grandchildren. She died, aged 93, in December 1981. Earlier in the

summer of that year, Gordon also passed away at Banbury Hospital. After their deaths, Mary left

Preston in 1982.

Mary wrote this piece after embarking on an Open University course. One of her essays was

about her job.

For over fifteen years, my job was as a village post-woman. I woke at about 06.00 and had to be at

the village Post Office by 06.45 to receive the mail from the little red delivery van. Then I sorted the

letters and parcels, arranging them in appropriate bundles for the sequence of delivery around the

village and outlying farms. I was scheduled to leave the Post Office at 07.15 – whether I did or not

varied, of course, with the quantity of mail to be sorted.

I was provided with an official bicycle for delivery – a hefty thing with no gears (so I walked up all hills)

and, considering this was a country round with rough roads and a seemingly unending supply of

fallen holly leaves and hedge trimmings containing brambles, extremely flimsy tyres with too easily

punctured inner tubes. The morning round was scheduled to finish at 08.55. This odd timing, and the

fact that the afternoon round was from 15.05 to 15.55, had something to do with the fact that my

particular part-time status required I should be employed for no longer than x hours (I think something

like 18¼) per week.

When I started the job, I was in my mid forties. Our four children were still all dependent – the eldest

at university; two daughters at grammar school; the youngest at the village primary school. My

husband was in a responsible, well paid job – accountant and company secretary for an advertising

firm.

Mary and Gordon with Erica, Ann and Chris

Windrush, Back Lane in 2006

We had a large house in a large garden. What, in these circumstances, was I doing applying for a job,

albeit part-time? My husband presumably brought in good money. My children still needed me, I had

more than enough to do at home. Was I bored with restricted village life? Was I planning to neglect my

children? Were we spending extravagantly, trying to “keep up with the Jones”?

Being both by nature unsociable in our private lives, my husband and I would probably have had no

idea what we should have had to possess in order to “keep up” with our neighbours; but he did buy

me every useful labour-saving device possible, for the simple reason that he thought I had too much

to do and needed them.

We both had a working-class background and it would never have occurred to us to employ someone

to do domestic work for me. The only “Joneses” were those my husband had to keep up with in the

course of his work – entertaining colleagues and clients, business lunches, golfing weekends. That,

and as he commuted daily between London and a little village in Hertfordshire, meant that he was

unable to give me sufficient housekeeping money to balance my budget.

So, my only reason at the time for applying for the job was that I needed the money. I was seeking to

supply the basic physiological needs of steady work and steady wages. “High wages” I never attained

though. As I was merely supplementing my husband’s contribution, this was less important obviously

than it would have been for someone who was the family main, or only, wage-earner. (Full-time

postmen are not exactly highly paid, but that is another story.) I started work in the mid 60’s at a little

under £10 per week. When I retired in 1980, I was earning over £30 a week.

Included also in a person’s basic physiological needs are “good physical working conditions”. It

doesn’t need much imagination to realise that there cannot be much better working conditions,

physically, than those of a village post-woman. One has regular exercise (almost) daily throughout the

year. The big advantage is that one has to do it – there is nothing optional about it. You can’t decide

one morning that you don’t feel like it. If it is raining, you still have to get out there. If it is so slippery

you can’t stand up, you put the chains on your boots and work out how you’re going to get round, but

you have to do it.

But then of course, you also see the trees breaking into bud in the spring, and the bluebells, and hear

the skylarks over the ploughed fields. And some summer afternoon you may only have a couple of

letters to deliver, so you can stand and chat or look at gardens, or wander away from the road and just

sit.

It is easy to protest that self fulfilment; doing useful, interesting work; forming felicitous social contacts

– are more important than the basic considerations of money and security. No doubt this is so,

especially among skilled and/or altruistic people; nevertheless, I suspect that more often than we care

to acknowledge, practical considerations come first. They certainly did with me, though once I had

gained peace of mind through no longer having money worries, then other values established

themselves – casual social everyday contacts had new meaning – I felt I was doing something really

useful – I appreciated the countryside around me. I had a considerable degree of autonomy; though

an employee, I was not directly under anyone’s supervision and it wasn’t difficult to feel that I was “my

own boss.”

Preston’s Post Office when Mary was a post-woman

On the other hand, there were many things that forced one to realise that one was most definitely an

employee and, at that, a quite insignificant employee of a large and, when appropriate, strictly rigid

public body. There was the customary Civil Service-type form of application, complete with supplying

references, statement of qualifications (I could claim none except an ability to walk long distances in

any weather) and, on acceptance, reading and signing the Post Office’s form of the Official Secrets

Act.

Postwomen of my grade had also to accept a standard two weeks summer holiday and no sick pay

under any circumstances. This frequently resulted in plodding on regardless of a heavy cold, and, in

the long run, this was the healthiest time of my life! – apart from the fact that, oddly for someone who

had to earn a living by walking, I was remarkably clumsy on my feet. I was capable at any time of

falling down a step, up a step or simply falling over my own feet. During my service with the Post

Office I once pitched over the handlebars of my cycle on a gravelly path and spent a month or so

looking like a victim of a serious mugging incident; broke a wrist in a fall on an icy path, and sustained

more sprained ankles than I can remember.

Each time I signed an acknowledgement that I realised I was not entitled to payment whilst not

undertaking official duties. The form I signed – obviously a standard one used for all employees –

included a space for “suggestions for future avoidance of similar accident” (the Post Office always

tried to be fair to all its employees). I eventually completed this with a suggestion that I look where I

put my feet in future. I’m sure someone at Head Office must have been thinking the same.

But also, during the long Post Office strike, village post-women, although they had nothing to do, were

paid in full provided they could assure the sub-postmaster that they were available. As I said, the Post

Office made every effort to be fair to employees, of whatever grade. Village post-women did not

belong to a union and were therefore not regarded as being on strike. However, we benefited from all

pay rises which the union gained for its members – hence the increased salary I mentioned earlier.

One outcome that was predicted of the Strike was that the volume of mail handled would never again

return to its previous proportions – people would find alternative satisfactory methods, or simply

discover that they could manage without. This did in fact happen, if our village could be considered

typical. Where we used to handle an average of, say, 6 or 8 bundles of letters daily (average 200

letters to a bundle), this was halved. 4 bundles soon came to be considered normal; 2 or 3 not

unusual. Increasing postal charges were clearly also partly responsible for this decrease.

I could not pretend that, as a post-woman, I objected to this lessening of the load! Sorting time was

reduced; I had less to carry. Delivery time did not change much, as one traversed the village anyway.

What it did mean, in fact, was that I often finished at my scheduled time, instead of dragging on after it

– which was a good thing, as the only occasion on which we were permitted to claim overtime was the

2 weeks immediately preceding Christmas. At all other times of the year, it was considered that a light

afternoon delivery compensated for a morning delivery that went on longer than it should have done.

The question of overtime was not a simple one, so far as the established, full-time postmen were

concerned. Before the Strike, it was essential for them to work, permanently, a considerable amount

of overtime if they were to take home a “living wage”. When wage settlements gave them improved

conditions, men (not surprisingly) no longer wanted to work overtime.

Not only that, but the Post Office no longer wished them to work overtime, because of the higher

rates. So more and more mail was left, unsorted, in the Sorting Office at the end of the day.

(Somehow, the decrease in quantity did not take care of this.) It used to seem to us, at the village end

of the chain, that the whole backlog was thrown out on a Saturday morning, so that, just when we

would have liked to finish on time, for a clear weekend ahead, we were until perhaps 11.00 delivering

lucky numbers and offers that couldn’t be turned down.

There were always people in the village who were eager to complain about the postal service and late

delivery was their main complaint. These were not business men who might, justifiably, be worried

about a late arrival (they were always courteous and, if they felt they had to enquire about a letter,

almost apologetic.) Those who “knew” what time their post should arrive were those who washed

dishes at kitchen windows looking out on the main street of the village and had something sharp to

say if Mrs N got her gas bill before they did.

They also complained, at intervals, if they thought I was not wearing regulation uniform. For their

benefit, it was a delight, one summer, to be able to cycle round the village wearing a scarlet T Shirt

emblazoned in gold across the front “Get the Most from your Post”, or on colder days, a hooded

sweatshirt proclaiming “Post Office Parcels – We Mean Business”.Apart from these, Post Office

uniform was sober enough, but one wore it – who would want to wear out their own clothes in the

service of the public? The only items I never wore were the wet-weather protective clothing. Fully

clothed in these, I’ll swear I could have helped man a lifeboat – I certainly couldn’t have walked, let

alone, cycled, eight miles round a country post round.

Complaints were never made to me, face to face. The usual way was for someone to “have a quiet

word” with the sub postmaster, which he duly passed on to me in an off-hand manner. This way

friendly relations were, superficially, maintained all round. My predecessor had advised me that it was

unwise to be too closely involved in village life and I soon realised the truth of this.

Conflict, on any level, was thus in the main avoided. If a complaint, either by phone or in writing, ever

reached the area Head Office, they were naturally bound to follow it up. The complainer received a

written acknowledgement; I received a copy of the complaint and was invited to make comments.

Occasionally, if it was a matter of timing or, once or twice, someone suggesting I was not following the

prescribed route, I would be informed that an inspector would arrive on such a day and travel the

route with me. This was a formality and I never heard anything further of the matter.

There was one complainer who occasionally went so far as to write a grumbling letter to the local

newspaper. When he accused me of opening his mail, I felt he had gone too far and was really upset.

My husband wanted to pursue him in some sort of (rather undefined) legal fashion; but it turned out

that Mr B and my husband both had the same solicitor, who refused to handle the matter and the

whole thing fizzled out!

The question of routing was more important that it might seem; my timing and, thence, my scale of

pay was allied to it. If new houses were added to the village, it had to be taken into account. The route

was changed little during the time I worked on the round, but had had a couple of major alterations

during my predecessor’s time. An isolated cottage in the depths of a local wood and one or two far-

flung farms were removed from the round and added to the duties of the little red van, following a

murder in a lonely lane.

Of course, like any married woman undertaking a part-time job, I was not answerable to myself alone.

My husband hated to be forced to acknowledge that I needed to earn some money for myself: “people

will think I can’t support my own wife and family.” Whether this was a middle class attitude or a hark

back to the working class pride of his dock-labourer father, I don’t know. He realised many wives did

work, and enjoy it – indeed, many of his colleagues were married women – but why did his wife have

to work?

Similarly, my mother, who lived with us for many years, was indignant that her daughter should

undertake such a menial task as delivering other people’s mail and tried for many years to persuade

me to give the whole thing up – long after it was quite obvious that I was having the happiest time of

my life! With her, it was quite possible that there was a lurking class consciousness, as she herself

had been a professional person, a teacher. Perhaps if I had had a profession and was returning to it,

she would have viewed things differently. But I was one of those girls who, though adequately

educated, never trained for a career – the reason being the intervention of the outbreak of World War

II.

The biggest change in the job of being a village postwoman is likely to have already happened in that

village where I was, and probably in many others too – it probably no longer exists. Since leaving the

village, I have lost touch, but while I was there I was scheduled for redundancy and all the other

postwomen in villages in the area had already been made redundant. In future there will only be the

little red vans..

Photographs from the Turl family album

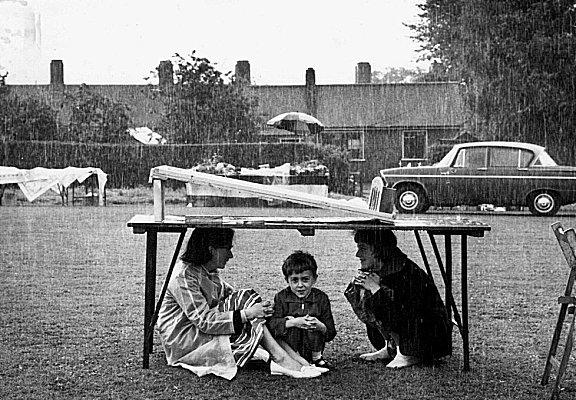

Anne, Chris and Erica sheltering during a Preston village fete

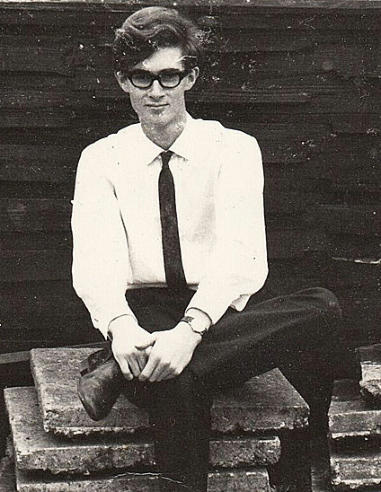

Chris on the doorstep of Windrush

June 1976 - Mary with ‘Nan’

St Martins Church outing circa 1961. (1) Mary Turl, (2) Ann Turl, (3) Erica Turl, (4) Chris Turl, (5)

Margaret Major, (6) Peter Meadows, (7) Eileen Newell, (8) Barbara Newell, (9) Clarice Bryan.

A class from Preston School c1960. With the teacher, Fred Orchard are: David Pateman, Trevor

Evans, Betty Watson, M Doyle, K Brown, L Shackleford, P Raffell, Frankie Barratt, William Standley,

A Griffin, Joan Andrew, Erica Turl, Janet Vaughan, K Boxall, P Rex and C Lenk.

John

Val Meyer-Hall (nee Humphries), her mother, Dorothy Humphries (far left),

Val Humphries and ‘Ben’ admire a baby

Anne Turl (right) with Margaret Major at a Princess

Helena College garden party

Mary died in March 2015, aged ninety-five, having returned to Hertfordshire to live in Letchworth, near

Chris and his family.

A bench in her memory now looks across the village green to where the Post Office used to be - the

place where she sorted the post every morning and afternoon before setting off on her round.

I am grateful to Mary’s daughter, Anne, and other members of her family for providing her mother’s

comments and the photographs.