Site map

The Books

A History of Preston in Hertfordshire

Margaret Corbett - Preston school headmistress

1811c

1766

Margaret Corbett (nee Edgar) exercised a significant influence on the development of Preston’s

children in the first half of the twentieth century as she was head mistress of Preston School

during two stints: 1913 - 1922 and 1938 -1945.

She was also prominent in local Women’s Institute activities,

being one of the founder members of the Preston and Langley branch.

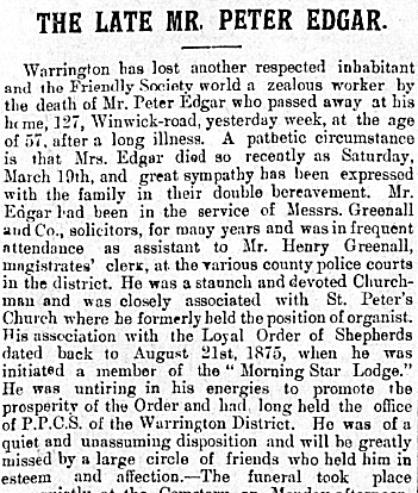

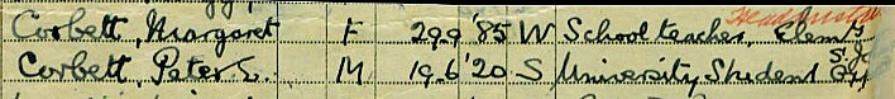

Margaret Edgar was born on 29 September 1885 in the industrial Lancashire town of Warrington,

which sits on a bank of the River Mersey. Her father, Peter Edgar, was a solicitors’ clerk and grocer.

The 1901 census revealed her future career path as she was described as a ‘pupil teacher’.

Then, in the early months of 1910, when Margaret was twenty-five, both of her parents died in quick

succession:

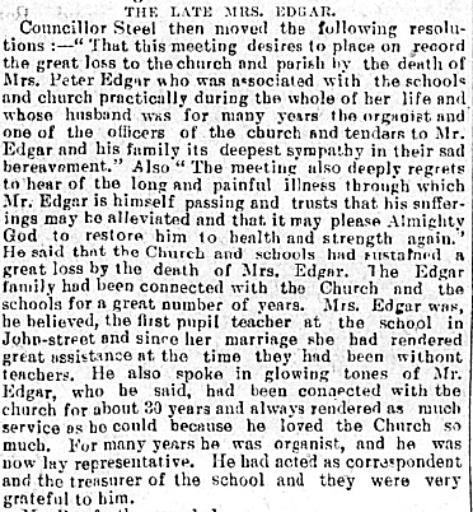

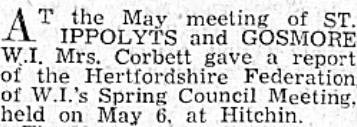

The devotion of both of Margaret’s parents to their Christian faith is clear, and her mother’s interest in

teaching and her father’s organ playing should also be noted.

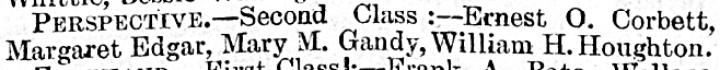

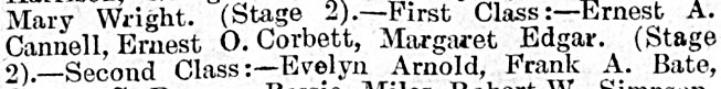

Earlier, in 1906, Margaret achieved the joint highest prize in all subjects at Warrington Training

College, excelling in enclid (ie maths), literature, geography and history.

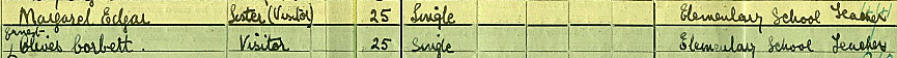

The 1911 census recorded Margaret as visiting her older brother, Charles Edgar, who was a journalist

living at Chelsea. She was now a qualified teacher and apparently accompanied by another

elementary school teacher, Ernest Oliver Corbett (who evidently preferred to be known as Oliver):

It transpired that Margaret and Ernest attended St Annes School, Warrington in 1901 and local

Technical Institute and Pupil Teacher classes in 1903, attaining prizes in the same subjects:

Mathematics

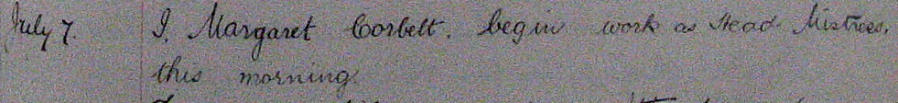

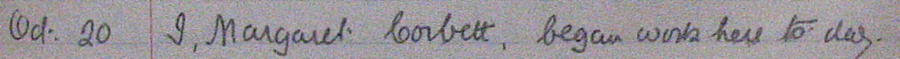

Margaret and Ernest married at St Anns, Warrington on 21 August 1911. On 7 July 1913, Margaret

began her first term of office as Head Mistress of Preston School, proudly writing in the School Log

Book:

Margaret was headmistress for the next nine years, overseeing the education of all those passing

through Preston School during the turbulence of World War 1 and its aftermath. The first school report

following her appointment, in 1914, noted that ‘despite disadvantageous circumstances…the result of

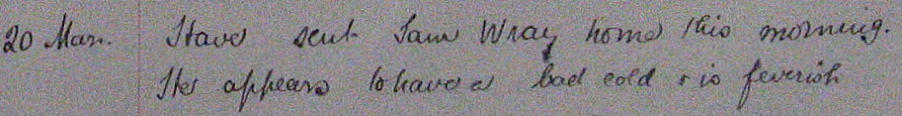

the examination was distinctly good and reflects much credit on the staff’. In March 1915, she dealt

with the intake of nine Belgian refugee children and in 1917 found the time to deal with my

eleven-year-old father:

Then, on 1 March 1918, Margaret noted that she had been given a grant of absence for a month or

two. The reason quickly became obvious when the birth of her son, Oliver Robert Corbett, was

recorded on 21 March 1918.

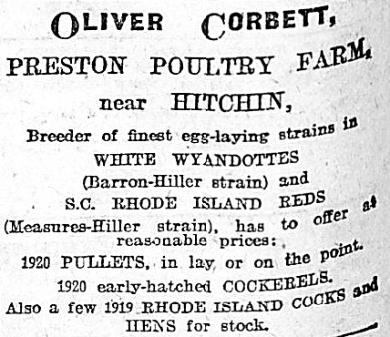

This is an apt moment to digress from school matters, to home affairs. In the spring of 1919, Margaret

and Ernest were living at Crunnells Green (in one of two newly-built semi-detached cottages on the

south-eastern side, shown below) with Ernest and Ethel Payne as their immediate neighbours. By the

autumn of 1920, the Corbetts had taken over the whole cottage and Ernest had already begun to farm

poultry (maybe as early as 1919). This advertisement was placed in October 1920:

However, in August of that year, it appears that he left this job because a new assistant was

appointed and Ernest was thanked for his ‘excellent services’. He had earlier clashed with the new

appointee on the subject of teachers’ salaries.

In the meantime, Margaret had expressed her interest in the Women’s Institute. Mrs Maybrick, in her

Scrapbook noted, ‘The Preston and Langley Institute was formed at an open meeting in the Preston

Club Room on January 3rd 1919. At the first monthly meeting, on January 8th, thirty seven members

were enrolled, of these, three are still members in 1953, Mrs. Worthington, Mrs. H. Peters and

Mrs. (Margaret) Corbett.’

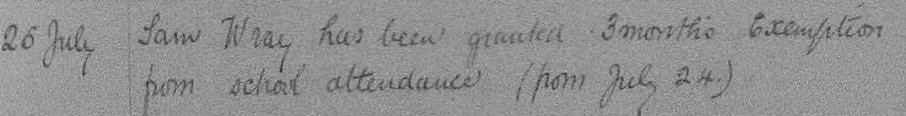

After her son, Oliver’s, birth, Margaret resumed work later than anticipated on 5 June 1918. Then, on

25 July, she granted my father time away from school (these details are included because they

illustrate and confirm her interaction with all the children in her care):

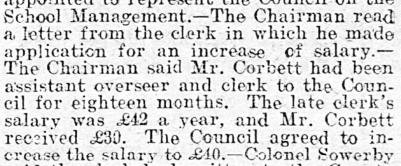

Since around September 1917, Ernest had been assistant overseer and clerk to St Ippollitts’ Parish

Council. The following announcement was made in April 1919:

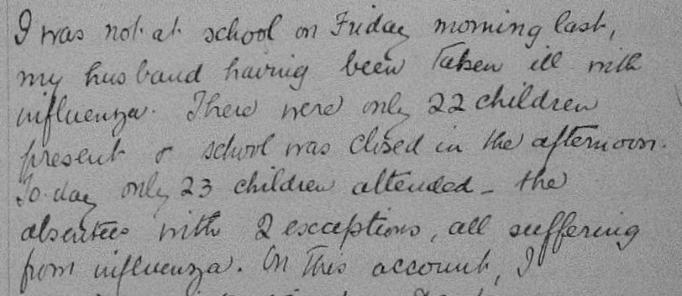

The ‘flu pandemic hit the area in November 1918:

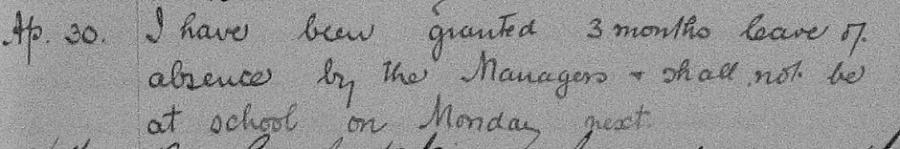

On 30 April 1919, Margaret wrote:

She was back in school on 7 September 1919, but was then frequently absent from school due to

illness. This was a hectic time in Margaret’s life juggling her work as head mistress,

WI activities, a newly-born baby and a large back-yard of chickens (it was also later revealed that her

husband was suffering from TB). It emerged that Margaret had given birth to a second son, Peter

Edgar Corbett, on 19 June 1920 which was a further drain on her energies. In addition to this load,

another potential complication was arrival at Preston of her brother in-law and his family and his taking

over a business with which he had little if any experience. These circumstances created a perfect

storm of stress for her. In July 1921, she was ‘ordered away by her doctor for two months for complete

rest and change’. The census found Margaret and Peter living with her sister Jane Ellen and her

husband, farmer Reuben Higham at Grappenhall, near Warrington. In December 1921, it was reported

that she had gone to St Bartholomew’s (in London) ‘for treatment as a result of heavy strain and over

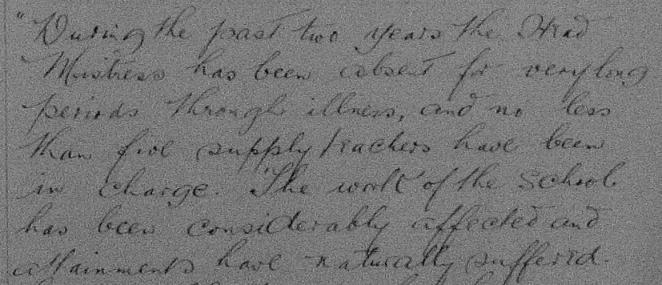

pressure’. The Log Book entry, 2 June 1922:

In August 1922 it was revealed that, ‘(Mrs Corbett’s) health gives no hope of her being able to resume

her duties..(she had been) so capable and faithful a head mistress’. Inevitably, on 12 September

1922, a new head mistress, Miss Deed was appointed.

The electoral registers show Ernest and Margaret at Crunnells Green Cottage without a break from

the spring of 1919 until the autumn of 1924 and Robert and Florence Corbett residing at one of the

new bungalows built by Douglas Vickers at School Lane between the springs of 1921 and 1922.

One somewhat odd fact is that in the 1921 census Ernest is shown as living at Crunnells Green with

his son, Oliver, and having a servant, May Jenkins (18, daughter of Ernest and Lizzie Jenkins and my

first cousin once removed). Perhaps she was to help with his son, Oliver - or maybe, Ernest was ill.

What is certain is that both Corbett brothers had given up poultry farming by the end of 1923 - Robert

returned to Warrington at the end of March 1922 and Margaret accepted a new position as head

mistress of Gravenhurst School, Beds (shown below) in April 1923. The last note of Ernest’s

occupying Crunnells Green Cottage was in the electoral register of the autumn of 1924.

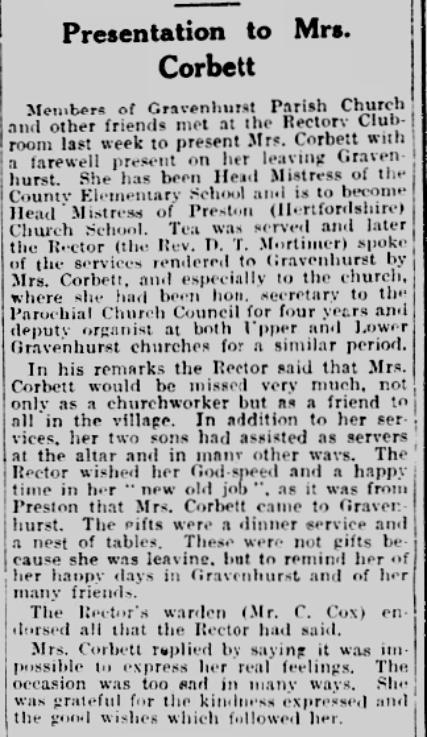

There are several newspaper references to Margaret at Gravenhurst: her school activity, her WI

involvement, playing the organ at village funerals and her work on the Rural District Council. So when

she left, to return to Preston in the summer of 1938, she was remembered for her community work

with affection:

Entry in Preston School Log Book, 20 October 1938:

There was just enough time for her to re-acquaint herself with Preston school and her pupils before

the fragile world peace was shattered once again. Margaret wrote in the Log Book on 4 September

1939 (with perhaps a feeling of deja vu), ‘School should have re-opened today but war having begun,

I have closed school until further orders’. On 9 September, a shift system was introduced at the

school to instruct both local children and evacuees who had already been sent to Preston and who

were living at Princess Helena College. Then, on 29 November, there was a note that she was going

into hospital for an operation. She returned to her school duties on 5 February 1940.

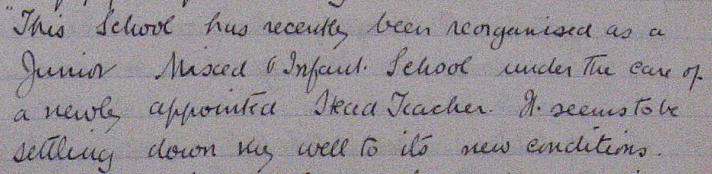

On 20 May 1940, there was a major change at Preston School. Margaret noted that some of the

senior pupils had gone to Hitchin and that ‘the school thus becomes a junior school’.

Her address was given as 15 Stevenage Road, Hitchin in 1939, having her youngest son for company.

Life at school continued to adapt to the war-time situation. Margaret took pupils to local places of

historical interest such as Minsden Chapel and Bunyan’s Dell and Cottage, Wain Wood. She also

attended occasional WI conventions and conferences. A school report found it to be ‘..a very pleasant

school to visit..the infants being cared for with affection…(and) a very genial response from juniors’.

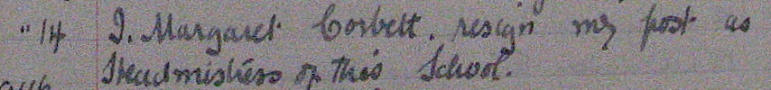

WW2 ended in the summer of 1945. Margaret’s tenure at Preston School ended shortly afterwards.

Apart from a recent visit to an optician, there had been no hint that she would step down, but resign

she did (aged sixty) on 14 December 1945:

Right, Margaret’s home at 15 Stevenage Road which is close to the

roundabout that links Preston and Gosmore to Hitchin.

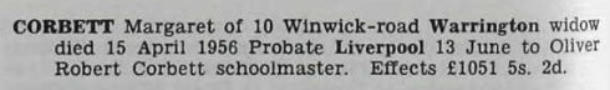

Margaret died at 10 Winwick Road, Warrington, which in 1939 had

been the home of her sister and brother-in-law, Fanny and Reuben

Higham.

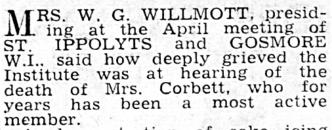

Though now retired, Margaret continued with her support of the Women’s Institute, but ill health forced

he to relinquish her position of Group Leader in February 1954.

February 1954

May 1954

May 1953

Margaret made an immediate impact on the performance of her new school. In 1925, a school report

stated, “This school, which had greatly deteriorated before the present Head Teacher came, is making

very good progress. There is now a pleasing tone, and the teaching is thorough.”

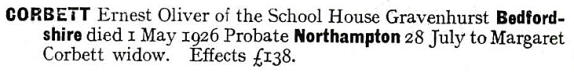

Ernest then died on 1 May 1926 at Gravenhurst. That he made a will suggests that his demise was not

unexpected.

The circumstances of his death confirmed the suggestions in this article (which was written before its

receipt). Ernest died from phthisis pulmonalis (TB) from which he had suffered for sixteen years, or

from 1910, which was before he married Margaret.. His occupation was given as ‘poultry farmer’

(which may have been a reference to his past work). His sister, Ada L Tutt, informed the registrar.

With hindsight, it was perhaps an unwise move for someone with phthisis pulmonalis and its

associated respiratory problems to become involved with keeping hens. There would have been

bacteria, fungi, spores, toxins and allergens in the farm’s organic and inorganic dust, odorous

compounds from hen droppings, feed, skin and feathers. As a result, respiratory disease is common

in poultry farmers. Ernest was dead within a few years of quitting the farm.

(I am grateful to Michael Oxley for allowing me to use his photograph of Margaret’s grave at

Warrington Cemetery)

The mistresses and pupils of Preston School circa 1917. Margaret Corbett is standing

with Rose Barker behind her in the entrance to the school.

Of Ernest and Margaret’s two sons, Oliver Robert and Peter Edgar Corbett

As both of Ernest and Margaret’s were sons of Preston, having

being born in the village, it is relevant to include details of their

exceptional lives and achievements.

By way of introducing them, in July 1936, there was a news

report of ‘Student Successes’ at Bedford School:

Of Oliver Robert Corbett (21 March 1918 - 12 February, 1989)

In September 1939, Oliver was in the household of his soon-to-be in-laws, Walter and Caroline

Goldsbrough at 33 Wibbersley Drive, Urmston. Both he and his future wife, Agnes Goldsbrough were

students and Oliver had registered for a commission in the Royal Corps of Signals.

1950

c1919

Oliver told his daughter he had to ‘cycle about 15 to 20 miles

to his school and back again when he was in his teens’.

His commission was confirmed in the London Gazette when he was appointed as a Second

Lieutenant, Emergency Commission, Royal Signals on 19 October 1939. After the War ended, Oliver

continued his association with the Royal Signals as a reservist, gradually moving through the ranks:

In 2006, Oliver received the ERD (Emergency Reserve Decoration) and eventually left the Royal

Signals with the rank of full Colonel. During the June Quarter of 1942, he married Agnes in the Barton

RD, which included Urmston:

Oliver studied at Oxford after gaining a scholarship.

1945-48 Reading “Greats” at Christ Church , Oxford

1948-64 Schoolmaster at Manchester Grammar School, teaching Classics

1964-80c Senior Assistant Secretary at the (Northern Universities) Joint Matriculation Board

1980c Retired on medical advice

Oliver and his mother,

Margaret Corbett, in 1954

Oliver in a Manchester Grammar School revue, 1953

Oliver and Agnes had three children, James Oliver, Rosalind and Peter R Corbett (who was born and

died in Bangor RD during 1954).

When Margaret Corbett died in 1956, there was a news report that Oliver and Agnes had travelled

from Manchester for the Memorial Service at St Martins, Preston, Herts:

Oliver died on 12 February 1989:

Of Peter Edgar Corbett (19 June 1920 - 31 August 1992)

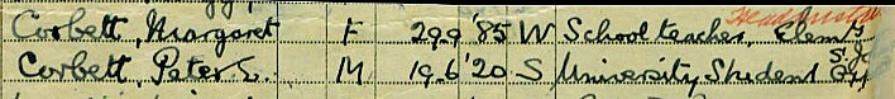

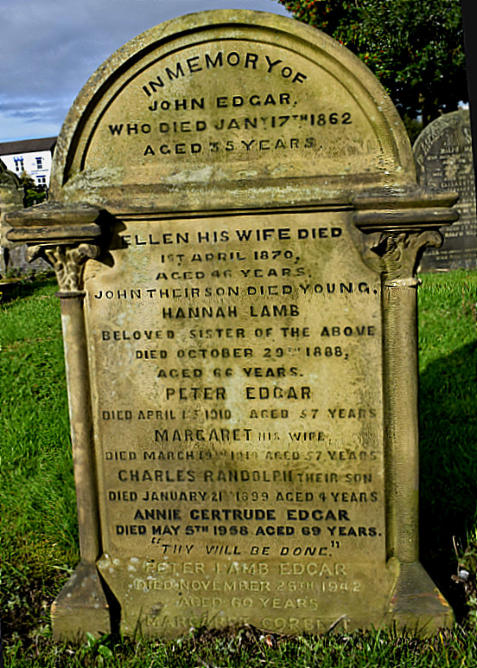

We begin this celebration of Peter’s life with his entry in the 1939 Register. He was then living with his

mother at 15 Stevenage Road, Hitchin:

Note that Peter had been awarded a scholarship at St John’s College, Oxford and was described as a

‘university student’. However, because of the outbreak of WW2, his education was put on hold. This

was the case with many young men at the time. My first cousin, Lawrence John Mills, had won a

scholarship to Birmingham University, but his education path was temporarily interrupted by his

contribution to the war effort. This was not necessarily an unfortunate experience.

We begin with a Peter’s potted history in Who’s Who and a news report of his wedding. Then follows

an affection bio (in italics) from The Independent newspaper which is interspersed with explanatory

comments.

1960

1942

Right, Peter (standing) and Oliver

“Peter Edgar Corbett, classical scholar and teacher, born Preston Hertfordshire 19 June 1920,

Thomas Whitcombe Greene Scholar and Macmillan Student of British School at Athens 1947-49,

Assistant Keeper Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities British Museum 1949-61, Yates

Professor of Classical Art and Archaeology University College London 1961-82, President Society for

Promotion of Hellenic Studies 1980-83, married 1944 Albertha Yates (died 1961; one son, one

daughter), 1962 Margery Martin, died London 31 August 1992.

PETER CORBETT, Yates Professor of Classical Art and Archaeology at University College London

from 1961 to 1982, and former President of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies, was

one of the acutest critics of ancient Greek sculpture and painting of his generation, and one of the

most influential.

The volume of Corbett's published work is small in comparison with his reputation, for he was a

perfectionist who could never bear to let an article or a book leave his hands until he was quite

satisfied with it. But he was no squirrel; on the contrary, he was vastly generous with his ideas and his

hard-won knowledge, and most of his best work had its impact in conversation with colleagues and in

lectures - a form of publication at which he was a master, and which, being provisional rather than

definitive, did not offend his ideal of perfection.

Corbett was born in 1920. From Bedford School he won a scholarship to St John's College, Oxford.

His firsts in Classical Mods and Greats straddled a wartime interlude, first in the Royal Artillery and

then for four years in the freer medium of the air. He flew Mosquitoes and used to claim, with more

modesty than truth, that the only time he was in danger was when he came within three inches of

Rouen Cathedral. In fact the lonely concentration of the RAF pilot made a lasting impression on him,

reinforced by his early post-war experience as Macmillan Student at the British School of Athens,

when archaeological research had to be pursued in the crossfire of the Greek civil war. Beneath the

banter Corbett was deeply serious, conscious always of the winged chariot and the need to use his

time.

In 1949 Corbett was appointed Assistant Keeper in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities

at the British Museum, then under the aegis of Bernard Ashmole, whom he was later to succeed (at

one remove) at University College. He revered Ashmole, for his unmatched combination of precise

scholarship, his artist's eye, and a limpidly clear and stylish gift of communication. It was a lively

department: with Reynold Higgins and Donald Strong for colleagues, the intellectual sparks flew.

It was also a time when liveliness was needed, when the museum groaned under the weight of its

heritage, stored away for the war and now to be brought back on exhibition in a more modern mode

than before. The Elgin Marbles took pride of place; and the years of close observation involved in

preparing them for the new Duveen Gallery gave Corbett the opportunity, and the inspiration, for his

first book, his deceptively modest King Penguin The Sculpture of the Parthenon (1959). It was, a

discerning reviewer wrote, 'almost faultless . . . at once lively and scrupulous'.

In those years also, Corbett undertook the exhibition and proper labelling of the vast study collection

of Greek painted pots, shoulder to shoulder in huge cases upstairs. It was, he told the Director and

Principal Librarian, who saw the display as less than trendy even then, a library of Greek mythology;

and the frown vanished.

The other achievement of this period was the re-composition of the frieze of the temple of Apollo at

Bassae, in Arcadia, (shown below) which was displayed in a magnificently lit exhibition. This, and his

efforts to have the frieze republished, proved to be Corbett's life's work.

Not among the greatest of Greek art, a generation later than the Parthenon in date and carved by

provincials, the frieze consists of separately composed blocks of random length and with almost no

overlaps, representing the two hackneyed subjects of Greeks in combat with Amazons and with

Centaurs, and found jumbled upon the ground. The challenge is akin to that of a jigsaw puzzle in

three dimensions. More closely than anyone, Corbett had studied the material both in the museum

and on site - the latter with his unrelated namesake GUS Corbett - and he was, besides, in total

command of the reports and drawings of finders and excavators in the early 19th century.

His reconstruction may not be quite right, though it has withstood the determined assaults of younger

scholars, even those fortified by the results of excavations made since Corbett's days in Greece. The

republication of the frieze, with the detailed reasoning behind his arrangement of it, occupied

Corbett's energies to the end of his life. But there were loose ends to be tied, and the work remains

unpublished though virtually complete.

In 1961 Corbett left the museum for University College London. Bernard Ashmole, who held the Yates

Chair from 1929 to 1948, for a decade in plurality with the British Museum Keepership, declared it the

research scholar's ultimate sinecure. Corbett found that he loved to teach, and transformed the

professor's role, taking a leading part in negotiations to start a new BA degree in Archaeology,

hitherto regarded in London as a purely postgraduate preserve.

Characteristically, his syllabus was to take four years, not three, in effect combining a full Classics

degree with a full course in Archaeology. To teach it, in those expansionist post- Robbins days, he

was able to enlarge the staffing of the department from one to two. At the same time, he devoted long

hours to postgraduate supervision, which he enjoyed. Corbett served both college and university as

Dean of the Arts Faculty, and undertook much else which inevitably kept him from his research - and

allowed others to pursue theirs. Convivial, an amusing conversationalist and raconteur, he was

always a popular figure in the Common Room; but he never lingered.

Corbett married twice. The death, from cancer, of his first wife, Bertha Yates, left him emotionally

shattered, and with two young children. In 1962 he married Margery Martin, a distinguished

Renaissance scholar, whose sense of a common enterprise restored his strength. Their riverside

home in Barnes became a Mecca for archaeologists and art historians, who came to enjoy not only

their hospitality but Corbett's encyclopaedic knowledge of fields far beyond the bounds of his own.”

He was named President of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies from 1980 to 1983 and

retired from the University of London in 1982.

On 24 October 1942, a de Haviland DH.98 Mosquito NF

Mk II (right) took off from RAF Castle Camps, Essex for a

night patrol with a crew of Peter E Corbett (pilot) and

Sergeant Clarence Landrey (observer), The plane’s

starboard engine failed and then exploded and caught

fire, yet was able to land safely with only minor damage

and no injuries to its two-man crew.

Pages from The Sculpture of the Parthenon which

illustrate its scholarly style. (See review below)

(There is an article featuring Rose at this link: Miss Barker) While realising that Margaret and Rose

were contemporaneous teachers at Preston School, the closeness of their friendship was not fully

apparent until some of the Corbett family photographs were sent.

Review of The Sculptures of the Parthenon 1959

Re: Margaret Corbett and Miss Rose Barker, teachers at Preston, Herts School

An informal photograph taken at Margaret’s home, 15 Stevenage Road, Hitchin

and shows Margaret (right) and Rose relaxing in the garden in around 1954

This view of Crunnells Green (aka West View Cottages) was sent to ‘Master Peter

Corbett’ of The School House, Gravenhurst, Ampthill on 27 June 1927 by Miss

Barker, who was sending her birthday greetings.

(I am grateful to James O Corbett for sending several family photographs and permitting them to be

used on this website)