Education - Literacy and Standards

With no state control until 1873, and the doubtful benefits of the plaiting schools, the quality of the

education of Preston children in the nineteenth century may be questioned. As a general rule, the

children of tradesmen were taught to read and write by their literate parents who needed this basic

education to carry on their business. The only guide to the literacy of the children of Preston is

whether they were able to sign when they married or were witnesses at the weddings.

The following is a rudimentary analysis of villagers who signed or marked at marriages. From 1814-

40 only 27 out of a specimen sample of 110 signed - 25%. From 1850 until 1875, remarkably this

percentage remained the norm. But from 1875 there was a very noticeable improvement: around

80% signed their names. If one allows a gap of, say, 14 years between finishing education and

getting married, there is evidence that the standard of education improved dramatically in the early

1860’s.

School Standards

The improvement in literacy noted above may possibly have been the result of applying the Revised

Code of standards which were drawn up by the Education Department in London. Attaining these

standards was important for schools because their receipt of grants depended on the performance of

pupils and their attendance. For older children success at Standard V meant freedom for them to

leave school and go to work.

The following are the criteria for each standard in reading, writing and arithmetic:

STD READING WRITING ARITHMETIC

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Reading monosyllables.

Next reading from

elementary book.

A short paragraph from a

book.

A short paragraph from a

more advanced book.

A few lines of poetry.

A short paragraph in a

newspaper.

Form letters from dictation.

Copy a line of print.

A sentence dictated in single

words.

A sentence dictated a few words

at a time.

A more difficult sentence as above.

A short paragraph dictated from

a newspaper.

Form and name figures up to 20;

add/subtract figures up to 10 orally.

A sum in simple addition and

subtraction and “times table”.

A sum in any rule including short

division.

A sum in money.

A sum in weights and measures.

A sum in practice bills of parcels.

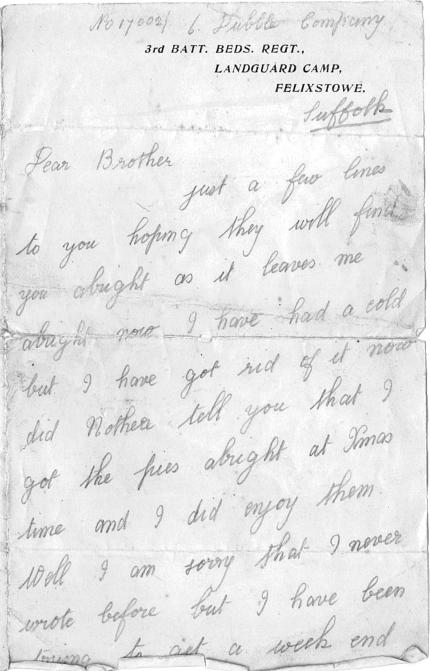

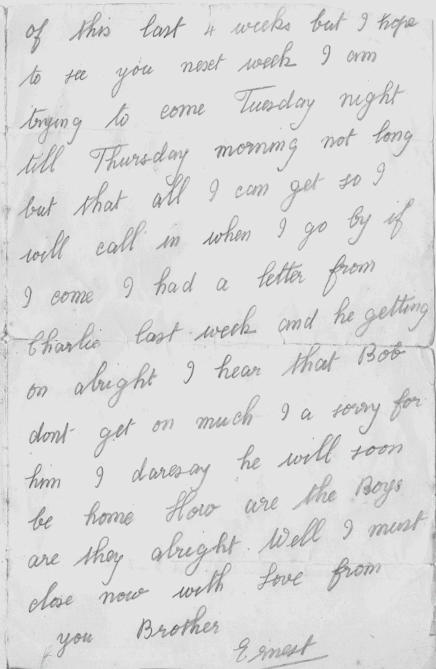

An example of applied education

It is possible to assess the standard of education in the 1890’s from a letter written by my uncle

Ernest Wray. There are some indicators of his intelligence and his interest in education in the school

log book.

He started school in 1896, aged four (which means he may well be in the front row of the school

photograph of that year which is reproduced on the education page). He then needed some extra

time ‘in the babies class’. His attitude toward school may be seen from the comment on 26 July 1899

when, on a summer’s day, he was punished for ‘truant playing’ with his cousin. The head mistress

commented, ‘this is a rare fault at this school’.

However, Ernest evidently was not ‘dull’ intellectually. The school log book mentions a regrading of

some pupils in 1896. Ernest is included with two boys who are said to be ‘very dull’. One may infer

that, as he wasn’t included in this assessment, Ernest was “brighter” than the other two boys.

Ernest left school on 26 June 1903 aged eleven and found work as a gardener. Almost immediately

after the outbreak of World War I, he enlisted in the army on 5 September 1914. During his initial

training, aged 23, he wrote to his brother. The quality of his writing, his spelling and depth of thought

can be assessed from this

letter (shown below):

To my untutored eye, Ernest’s handwriting seems adequate and clear. His spelling is good and the

letter is reasonably set-out. The content is perhaps a little ‘lightweight’ but one wonders how many

letters Ernest would have written. Tragically he was killed in action on 24 August 1915. Link to Ern

Wray