Norah and Julian Gribble and

Leslie Grace Seebohm (nee Gribble)

Leslie Grace Seebohm (of Poynders End) and her mother, Nora Gribble, were buried at

St Martin’s, Preston in 1913 and 1923 respectively.

This is the story of Norah’s life,

Leslie’s burial and Norah’s son, Julian Gribble, who is memorialised in St Martins Church.

The Quaker, Frederic Seebohm, was born at Bradford,

Yorkshire in 1833 and married Mary Ann Exton in 1857.

He wrote the acclaimed work, The English Village

Community which drew its inspiration from the area

around Hitchin. The couple had six children: five

daughters and a son, Hugh Exton Seebohm, who was

born in 1867. In 1901, Frederic was living at 84 Bancroft,

Hitchin and was described as a banker and magistrate.

Meanwhile, the merchant, George James Gribble,

married Norah Royds (born 1859 at Great Boughton,

Cheshire) at Chester in 1881. Included among their children was a daughter, Leslie Grace Gribble,

born in 1883 at Chelsea.

Hugh (then a Hitchin banker) and Leslie married in early 1904 at Biggleswade, Beds and moved into

a newly-built house at Poynders End (above) in 1906. They had four children: Derrick (born 1907),

the twins Frederic and George (born 18 January 1909) and Fidelity (1912) Link: Seebohm.

The news report of the funeral of Leslie Grace Seebohm - 24 September 1913

In the very sudden death of his wife, the sympathy of the town’s people of Hitchin and of a wider

radius is extended to Mr. Hugh Exton Seebohm, a member of an old and revered Hitchin family.

The death came with such unexpectedness that a tragedy of grief was experienced by relatives and

friends. Previous to Saturday Mrs. Seebohm was apparently in perfect health. With her husband she

had just returned to their house at Poynder's End, from a holiday in Brittany. In the early hours of

Saturday morning Mrs. Seebohm was seized with illness and Mr. L. S. Barnes, of Whitwell, was

immediately summoned, but the attack was such that death occurred at a later hour the same

morning. A London physician who had been also summoned stated on arrival that everything possible

had been done.

It was on January 28, 1904, that Mr. Hugh Seebohm was married at Henlow Church to Miss Leslie

Gribble, the late Mrs. Seebohm being the second daughter of Mr. George Gribble (and Norah Royds),

then resident at Henlow Grange and later at Biddesdon, Hants. Nine months previously in the same

church Miss Phyllis Gribble, a sister, was married to Mr. W. A. Fordham, a member of another well-

known Hertfordshire family.

Mrs. Seebohm was related by marriage to the Rowntree family, Mr. Joseph Rowntree, chairman of

the firm of Rowntree & Co. Ltd., having married in 1867 Miss Emma Antoinette Seebohm. Mr. Hugh.

Seebohm is the only son of the late Mr. Frederic Seebohm, the historian and a director of Barclay's

Bank, who did so much for the cause of education in Hertfordshire. Mr. Hugh Seebohm has been

elected to several important public offices so ably filled for many years by his father.

There are three sons and one daughter of the marriage.

Beside the little Parish Church of St. Martin, Preston, the mortal remains of Mrs. Hugh Exton

Seebohm were interred on Wednesday. It was a scene impressive in character and many eyes were

dimmed among those who had come to pay a last tribute. The esteem in which the late Mrs.

Seebohm was held in the village of Preston was fully manifested by the presence of a large number

of parishioners and there was a touching incident when a number of children in charge of a teacher

visited the graveside a little while after the service had concluded..

It was a simple service by the graveside, for the cortege did not enter the church. The mourners were

met at the entrance to the churchyard by several choristers from St. Mary's. Hitchin, with Mr. H. G.

Moulden and the robed clergy—the Rev. E. P. Gough (rector of Downham Market), the Rev. J. W.

Capron and the Rev. E. P. Tallents. The Rev E. P. Gough conducted the whole service. On reaching

the graveside the hymn, "Jesu, lover of my soul", was sung, and the short but impressive service

concluded with the singing of the hymn "Holy, holy, holy - Lord God Almighty!"

There were many tributes to the deceased in the form of flowers, chief among which was a simple

and beautiful wreath of blue plumbago from the husband; a bunch of arum lilies from "Mother and

Father " and a similar bunch from "Brothers and Sisters." Mrs. B. P. Gough sent a floral tribute

bearing the following inscription: "For my darling Leslie, with loving thoughts and prayers, from Ellen,

who loves her so very much. How her bright and glorious spirit shines! God grant unto her eternal rest

and let light perpetual shine upon her."

The immediate family mourners were: Mr. H. E. Seebohm (husband), Mr and Mrs George Gribble

(parents). Mrs Wolverley Fordham and Mr W. O. Fordham (sister and brother-in-law), Miss Vivien

Gribble (sister), Mr Phillip Gribble and Mr Julian Gribble (brothers). Mr. Seebohm's relatives present

included: Sir Rickman and Lady Godlee (sister and brother-in-law), Miss Seebohm and Miss Hilda

Seebohm.

Among those present were :—Mr. and Mrs. Milne Watson,

Mr W. F. Dalton, Mr W. Tindall Lucas, the Rev. F. H.

Procter., Mr. Edward Brown (Luton), Mr A. Spencer, Mr R.

de V. Pryor,. Mr Theodore Ransom, Miss Ransom.

Mr Theodore Lucas, Mrs F. A. Wright, Mr and Mrs H. E.

Harrison, Mr T. Fenwick Harrison, the Rev. R. S. Bagshaw,

Mrs Armstrong, snr., Mr and Mrs Armstrong, Mr and Mrs A.

J. G. Lindsell, Mr W. O. Times, Mr Francis Shillitoe, Mr

Francis Ransom. Mr Jack Ransom. Mr and Mrs W. Bailey

Hawkins, Miss Bailey Hawkins, Mr and Mrs R. J. W.

Dawson, Mr Lister Harrison (Woodford), Mr Frank H.

Barclay (Cromer). Mr R. Seebohm (Luton), Mr Rushbrooke,

Mr L. S. Barnes (Whitwell), Mr M. H. Foster and

Mr R. Vaughan,

The grave was lined with evergreens, Rose of Sharon

berries, lilies, roses, plumbago and silver and golden

variegated ivy by Mr. H. Peters (gardener at

Poynder's End), Mr. W. Sharp (gardener at Offley Holes to

Major Richardson), and Mr. J. Swain (gardener to Mr. J. C.

Priestley).

The coffin was composed of brown English oak, with plain

brass fittings, and a brass plate bore the inscription: ‘Leslie

Grace Seebohm; born 1883 ; died September 20, 1913’.

Leslie Seebohm’s grave (shown

above) is in the north western

corner of St Martin’s graveyard.

Of Norah Gribble - mother of Leslie Seebohm

In his book, Norah’s son, Philip, provided a description of his mother:

My mother in her lighter moments was capable of charming flashes of frivolity, but her normal

reaction to life was one of intensity. She was a marvellously beautiful woman, blessed with divinely

golden-red hair, and immense, almost violet eyes, varying in depth with her moods; her full, sensitive

mouth, firm chin and small but magnificently carved head were a delight. She was proud of her legs,

and often pulled her skirts to her knees to allow us children to admire their symmetry.

She had very advanced views, was self-centred, artistic, intellectual and convinced that her family

were beyond reproach, an outlook that made her intolerant of even minor faults, and encouraged her

to exaggerate their importance to a point at which she found an excuse for melodrama. Much as we

all loved her, my mother's presence was usually accompanied by a sense of strain, and it was only

when she left the house that the family could relax.

She took an active part in local government, mainly from a sense of duty I think, but it was religion

and its trappings that dominated her life. There were weeks when, day after day, she would lock

herself in her studio and sit rapt in meditation while pondering over the manuscript of one of the

several books she wrote on religious subjects, among them My Way Out, published by a close friend,

John Murray; or at other times she might be writing poetry or be lost in painting some canvases. Her

poetry was moving and was an outlet from frustration and a form of release.

My mother was a rather frightening and utterly lasting influence on the characters of all her six

children. Not only was she a thinker and a writer, but also a creative artist, and in her early or

orthodox phase she was a competent portrait painter; she had studied at The Slade as a girl and

taken her work very seriously. In later life she despised representational jest and emotive fragments,

and concentrated on her search for new means of expression and the use of new media. Several

rooms at Henlow were covered with her murals, executed in tempera.

One and all we had to learn silence because Mother's moments of inspiration must never be spoiled

by slamming doors, noisy footsteps or the yelling and shouting of the average large family. The rage

and genuine agony that were the reaction to any such interruptions had to be seen to be believed.

Our behaviour had been an outrage, the extent of which we soon grasped and the importance of

which we never forgot; so now I am a good guest and have often been told by my hosts that they

would hardly know that I was in the house.

My mother was always boasting about "our family", by which she meant HER family, the royal family

of Royds.

Of Norah’s son - Captain Julian Royds Gribble

What follows is an article written by John Medland that was published in the

Newport Beacon (Isle of Wight) in November, 2007 (publisher - I W Beacon Ltd.).

Julian Gribble was born in 1897 and educated at Eton.

At 9.30am of March 23rd 1918, as the final German bombardment

began, Captain Julian Royds Gribble reported to Battalion HO that

masses of German infantry were advancing towards them. Two

days earlier the Germans had launched a million man offensive

which had over-run a fifty-mile stretch of the British Western Front.

British soldiers were surrendering in tens of thousands. The 10th

Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment dug in behind the

British lines and were given orders “to fight to the last”. As the

hillside erupted in explosions and the shattered British army

withdrew in chaos around them, the placid sights and sounds of

the Isle of Wight, where many of these men had trained must have

seemed a world away.

This Remembrance Sunday also falls on Armistice Day. At 11 am

on the 1st November 1918 the guns on the western Front of the

First World War (1914 -1918), finally fell silent. As we look at the

long lists of names on our war memorials it is hard to visualise

these were sons, brothers, lovers, husbands, fathers and friends.

However if we take just one name, one man who knew and loved

the Island, perhaps we can come a shade closer to understanding.

Julian Royds Gribble was born into a privileged wealthy family on

January 5th, 1897. He was enrolled at Eton school in 1910. He

grew up a tall, graceful. and popular boy. interested in art and

music. When the first World War began Julian transferred to the

officers' training school at Sandhurst.

The Isle of Wight

In early 1915 Julian Gribble was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment

and was posted to train recruits at Albany Barracks, Parkhurst.

In a letter to his mother, Norah Gribble, from Parkhurst in 1915: “Although we have sent out over

8,000 men to France from the battalion since the war began, we sent our first draft to the Dardenelles

yesterday. I went down to Cowes to see them off.”

Julian spent his off-duty moments exploring the Island on his motorbike. He loved the countryside

and the seascapes. He took advantage of every sporting opportunity and made friends “with any sort

of man” in his mother’s words “ who had led any sort of real life”. His love of the Island is reflected in

the many letters he wrote to his mother from Parkhurst, Culver Down and The Wheatsheaf in

Newport which she published after the war.

In the winter of 1915-16, Julian was posted to Culver Down gun battery “a Godforsaken spot on the

extreme end of the Island” Later he wrote "There are thirty men under me here. I have to do

absolutely everything for them, which is really rather Interesting - find and pay the women to do their

washing, arrange with the contractors for food, mount the guard and visit sentries by day and night.

This last is the worst job of all at night. Last night it was blowing as I have never felt it blow before,

driving sleet with it"

Conditions were basic and Julian shared them with his men. "My hands are sore today and covered

with blisters, as we have been digging a subterranean passage in the chalk, which is very hard work."

The stunning sea views provided some excitement. "a torpedoed Dutch steamer of 3,084 tons came

in yesterday escorted by a destroyer. Her engines had been put out of action and she was being

towed along by two tugs. The same submarine torpedoed a French barque off St Catherines. Both

these appeared in the papers this morning, but we actually saw them yesterday"

He remained on the Island for a year, sometimes taking drafts of newly trained troops as far as the

French ports. "Nobody was in such a good position" his mother wrote, "for realising the ravages of

war as those who spent their time in filling and filling again its ravening jaws and those who saw its

wreckage perpetually cast up into the military hospitals." (The regiment enlisted a total of 47,500 men

during the war, of whom 11,500 lost their lives.)

(On a personal note, my grandfather was posted to Sandown IOW in October 1917)

Posting to the Western Front

In April 1916 Julian was ordered to France. Over the next six months without leave he was in the

thick of the fighting of the Battle of the Somme. In October he was sent home as sick with "trench

fever". Although he was recommended three months rest after just one month he reported back to

Parkhurst. From there he was posted to the 10th Battalion with the rank of Captain. At a time when

the average life expectancy of British army officers at the front was 17 weeks Julian was already a

veteran. In peacetime he would still have been at Eton.

Julian was a good officer. He got to know the men of his company as individuals, learning in detail

about their lives. Julian's Sergeant wrote "I am an old man in the service of my country, but I have

never loved or respected any one so much as he, God bless him" Julian spent the winter of his

twentieth birthday in the mud, frosts and floods of Flanders "wet up to the middle and never warm or

dry. He had another short leave in 1917 and then endured the final dreadful winter of the war back in

the trenches. In the opening months of 1918 Julian was due leave, but after the epic horror of the

hundred day Battle of Paschendaele, the British army was seriously undermanned. Julian's leave

was postponed month after month.

The Kaiser’s Battle

In the darkest hours of 21 March the unsuspecting British III and V Armies were shocked by the most

intensive barrage of the war. In eight hours 6,500 German guns delivered 1.16 million poison-gas and

high-explosive artillery shells into the British defences. Supported by the close fire of over 5,000

mortars, the barrage moved forward 200m every four minutes, annihilating defences and leaving the

surviving defenders deaf and stunned. It was the beginning of the decisive German spring offensive,

code named Kaiserschlacht, the "Kaiser's Battle".

The 10th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshires were in reserve in the III Army when the German

barrage began. Julian dashed off a goodbye letter. 'All I pray to God is to give me strength to lead D

Company well – as they deserve. I know mother that in any case you will not grudge to England your

youngest son. We have always been cheery so lets go on being so – thanks to you and Father I have

had as happy a time in this world as possible, almost."

Behind the creeping barrage 76 German divisions, equivalent to the entire British Army in France,

advanced. They were led by "Stormtroopers" armed with wire-cutters, grenades and flame-throwers.

Behind them came large "battle groups" of infantry with field artillery and heavy machine guns,

followed by more masses of marching infantry. To Sir Arthur Conan Doyle it seemed as if fresh

divisions were "rolling in like waves from some inexhaustible sea."

The four infantry companies of 10th Battalion hastily dug in along 1,600 yards of the Hermies Ridge

behind the rearmost British defences with orders to hold the position to the last man. The Battalion

was supported by its own battery of field artillery, flanking infantry, and further batteries of artillery and

heavy machine guns.

On the second day of the offensive the Germans began to shell these new positions and the

command structure of the British Ill Army began to break down as it joined the V Army in a fighting

retreat. The next morning, as Julian reported the Germans massing to attack, the Battalion's artillery

were galloping away under conflicting orders. As the German attack intensified more supporting

artillery and infantry retreated. The battalion found itself increasingly isolated and surrounded. Even

the HO staff and any retreating stragglers they could rally were thrown into the desperate fighting.

They held on for three hours.

By 12.30 just D Company was left holding onto the top of the ridge. When he was the last officer

standing Julian finally allowed his men to retreat, keeping six with him. Private Madeley was one of

them. "I got hit and I am glad to say I broke through, but not so with the Captain" Julian was last seen

emptying his revolver into the final assault. "I saw him go down under about seven big German brutes

and that was the last I saw of one of England’s finest officers".

The "Kaiser's Battle' lasted just two weeks. A new French Supreme Commander combined dogged

British resistance with a French counter-attack. 425,000 men fell on all sides in fifteen days of fighting

that is now almost entirely forgotten.

The citation to the Victoria Cross in the London Gazette of 28 June 1918 read:

‘For most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty. Captain Gribble was in command of the

tight company of the battalion when the enemy attacked and his orders were to hold on to

the last. His company was eventually entirely isolated, although he could easily have

withdrawn them at one period when the rest of the battalion on his left were driven back to a

secondary position.

His tight flank was in the air, owing to the withdrawal of all troops of a neighbouring division.

By means of a runner to a company on his left he intimated his determination to hold on until

other orders were received from Battalion HQ and this he inspired his company to

accomplish. His company was eventually surrounded by the enemy at close range, and he

was seen fighting to the last. His subsequent fate is unknown.

By his splendid example of grit Captain Gribble was materially instrumental in preventing for

some hours the enemy obtaining a complete mastery of the ridge, and by his magnificent

self-sacrifice he enabled the remainder of his own brigade to be withdrawn as well as

another garrison and three batteries of Field Artillery.’

Prisoner of War

Julian's body was robbed and left for dead, but later it was discovered that he was alive. He began to

make a good recovery in Hameln Hospital from 20 April 1918 which was associated with the POW

camp at Karlsruhe, but found himself on the losing side in the terrible final months of the war. The

Allied blockade of Germany was so effective that the whole country was in a state of starvation.

When Julian arrived at the new officer's prison at Mainz Zitadelle, he and his fellow inmates suffered

six weeks starvation before the first Red Cross parcels arrived. In May, Julian heard that he had been

awarded the Victoria Cross for his stand on Hermies Ridge. The other officers saw the letters "VC" on

the envelope and carried the embarrassed invalid about the barrack square on their shoulders. On 4

June Julian celebrated Eton's special day with four other old Etonians "with a soup made of a few

scraps of lettuce".

The First World War finally came to an end after the German Revolution of October 1918. By this time

some two million German civilians had starved to death, but worse was to come. A bird 'flu' had

mutated. We know it as "Spanish Influenza". After more than four years of wartime food shortages it

became the greatest pandemic in history. Recent estimates put the death toll at more than four years

of wartime food shortages it became the greatest pandemic in history. Recent estimates put the death

toll at 50 to 100 million worldwide.

Eight days before the Armistice Julian himself fell ill. On the morning of November 24th his fellow

prisoners were released and boarded the train home. Julian was left alone in the Royal Fortress

Hospital, Mainz. He died shortly after midnight. His last words were to dismiss his nurse: "Go away

gnadiger Frau." (gracious lady). The following day the French army arrived with food and medicine.

Taking his love for this Island into captivity with him, in his last letter to his mother he wrote "The only

trees we have are a row of small planes which I imagine In different surroundings - boulevard at

Amiens - a sea front at Cowes."

He was first buried at Mainz Military Cemetary in the grounds of Mainz Zitadelle, but his remains were

later moved to Niederzwehren Cemetery, Kassel (III F4)

Julian's mother never recovered from the loss of her son. She visited his grave on 6 November 1919.

Her older son describes his embarrassment as "my poor mother kneeled at the grave and wept. She

scraped the snow away with her bare hands and kissed the ground, gathering earth and leaves in her

fingers as if these were part of her son."

This description of the grief of Norah Gribble brings into stark relief a grief that was echoed throughout

eleven million homes and families in all the lands whose sons were lost in this pointless war.

These eleven million men & boys may have died for misguided notions of European nationalism, but

they died to give us a better future.”

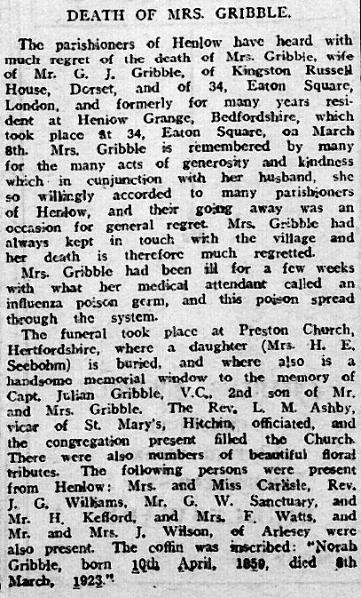

The impact on Norah Gribble of losing her son and daughter

‘....to my mother's everlasting grief, he (Julian) died there on

Armistice Day, a victim of Spanish Influenza then sweeping

Europe. Many millions died, and their deaths far exceeded

the total casualties of the whole war. My mother was broken

hearted. She went into a spiritual decline and never

recovered a balanced view of life. The early death of my

sister Leslie after a few years of marriage had much

affected my mother. She believed that Leslie's death was

due to carelessness and she brooded over this loss.

Julian's death, again, as she thought, due to neglect,

seemed to break down her final defences. She was the

victim of regret and mourning throughout the remainder of

her not very long life.’ Extracted from Off the Cuff, an

autobiography by Philip Gribble.

The impact of his mother on his life is clear in Philip’s book.

He even describes in detail an experience when his mother,

six months after her death, came ‘right into my arms. I could

feel her hair cut short at the nape of her neck’. Yet, his

mother’s death is only mentioned in passing in his book,

when he describes the deaths of three people in quick

succession who included ‘my mother in 1923’. Perhaps he

considered his earlier comments a sufficient explanation of

her decline. The news cutting shown right states her

medical attendant reported somewhat vaguely that she had

been ill for a few weeks with an ‘influenza poison germ…

(which) spread through her system’.

The photograph of Julian in The Book of Julian which included all the letters he wrote to her, from

his prep school days up to the time when he was a prisoner of war.

Norah Gribble, painted by John Singer Sargent in 1888. Her son, Philip, described her as

being blessed with divinely golden red hair and immense, almost violet, blue eyes’.

Her hair colouring is echoed in the portrait by the under-painting.

Of Julian Gribble

More than a century has passed since the death of Julian and it can now be revealed that he was the

father of a baby girl. This news can be published now as it is in the public domain. The catalyst is

DNA evidence which confirms an oral tradition.

As reported earlier, in early 1915, Julian was posted to the Isle of Wight. During the winter of

1915/1916, he was moved to the Culver Down Gun Battery, which was close to the small town of

Sandown beside the sea. The purpose of the battery being to deter naval attack, its two 9.2-inch

guns were not intended to cover Sandown Bay. But they could fire as far as Spithead, bombarding

any enemy ship entering The Solent.

Among his duties Julian ‘found local women to do the washing of his men’. In April 1916, he was

assigned to a war front in France. He later had a short leave in Britain in 1916, which was probably

when his daughter was conceived, during November. Soon afterwards he returned to the theatre of

war and was initially declared to be missing and then found to be a prisoner of war. He died at Royal

Fortress Hospital, Mainz in Germany on 24/25 November when his daughter was fifteen months old.

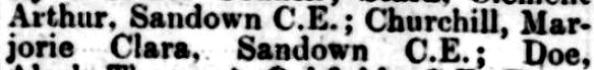

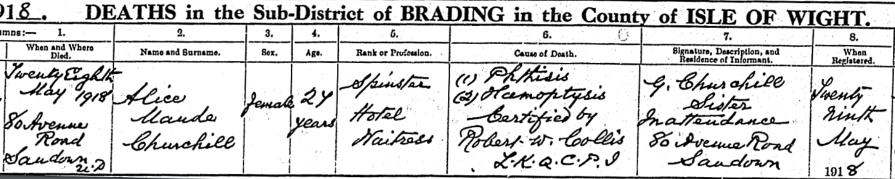

This is a copy of his daughter’s birth certificate. She was born on 9 August 1917 at her parents’

home:

The chalk outcrop of Culver Cliff. To the left is Sandown, with its pier. The Sussex coast is in the

distance. The position of the Gun Battery is shown by

*

*

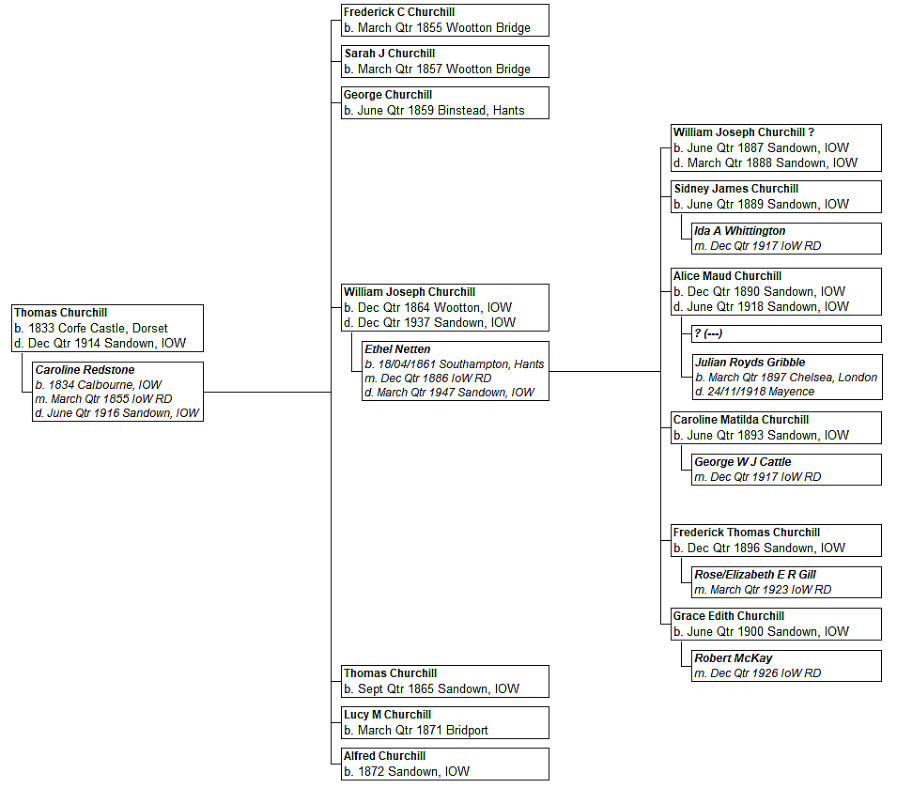

Now, some information about the Churchill family. Alice’s grandfather,

Thomas Churchill, was born at Corfe Castle, on the Dorset coast

near the Island. His wife, Caroline, was born at Calbourne IoW.

The couple initially lived at Wootton Bridge, IoW (where Alice’s father,

William Joseph Churchill, a chimney sweep, was born in 1864)

before moving to Brading, a small inland town which was less than

two miles north of Sandown. Thomas was a carter for a coal

merchant.

William and his wife, Edith, had six children (one of whom died in

infancy) and by 1881 they had settled in Sandown and were living in

the four-roomed 2 Fort Mews, Avenue Road, which was less than

half a mile from the beach. It’s likely that the Churchills stayed in this

house for several decades as the widow Edith and her family were

living at 80 Avenue Road (shown right) in 1939. The house facade

was probably of brick in the early 20thC.

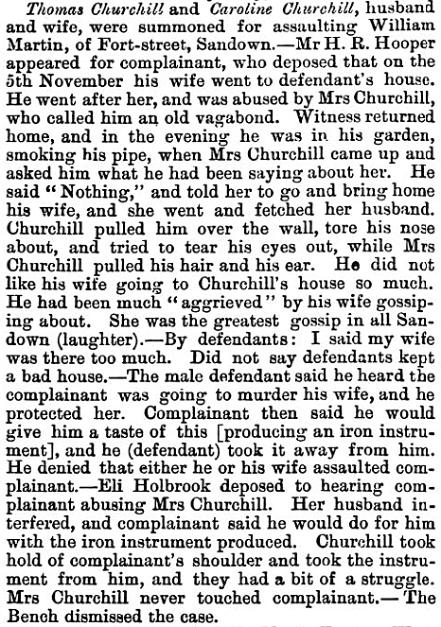

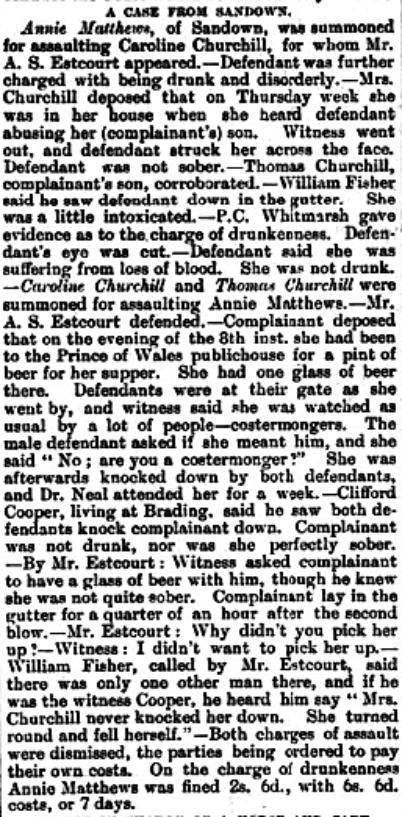

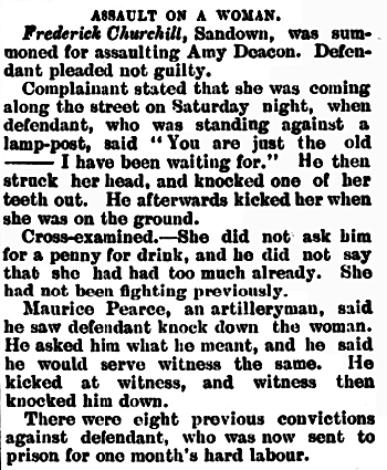

Thomas and Caroline Churchill were often before magistrates for assaulting folk together - something

that was fairly unusual. In October 1878, there was a fight between the couple and Frederick Jacobs

and two other later disturbances were reported. Caroline was also fined for assaulting a policeman

who was trying to cuff one of her sons (see three cases below)

November 1881

September 1887

September 1885

May 1894

William’s older brother, Frederick Churchill, was a mariner. In 1885, he survived the sinking of the

brigantine, Charles George, off Beachy Head after a collision with the SS Cathay, when at least two of

its crew perished. Between 1876 and 1900 Frederick was fined for drunkenness and in 1901 he was

accused of assault:

In September 1885, Alice’s father, William, his brothers Frederick and Alfred, their mother, Caroline,

were involved in an extraordinary fracas with police at Sandown. At 22.45 in Wilkes Road, Frederick,

who was drunk, was being led down the street by his brother, William. He saw a police constable and

said, ‘Here’s the ----- who gave evidence against my little brother. I’ll go for him’. He knocked the

constable down, tore his staff from his grasp and hit him with it three times about the head. He lost a

tooth. William tore his shoulder strap and also struck him.

A sub-plot was that Sandown had no lock-up to which they could take Frederick. The police went to

his home the following day to arrest him. He ran off. When caught, he bit a constable on his hand.

Caroline got involved (as reported earlier) and Alfred (aged 14) kicked a constable and struck him with

five or six violent blows to his back. Frederick also bit a constable’s thigh - ‘He was like a a wild

animal’. He was sentenced to six months hard labour; William, one month (as his offence was passive

rather than active) and Caroline and Alfred were fined 10/- each and costs.

This is the family background from which Julian’s partner, Alice

Churchill, came.

The 1911 census enumerator found her on the mainland at 38

Elphinstone Road, Southsea. She was a maid serving Mrs

Marion Bush, an apartment house keeper.

Three years later, in 1914, Alice was in London. This was

revealed by the 1921 census - but we are running ahead of

ourselves here. Let us return to Alice at Sandown.

In around late 1916, Alice (shown right) is thought to have been

working at the Seagrove Hotel, Sandown and one of its guests

was Julian Gribble.

This aerial photograph from 1932 shows the position of The Seagrove Hotel (ringed)

which backed onto the esplanade in a ‘Premier position facing the sea’ and was

immediately behind a War Memorial. Its front entrance was on Sandown’s High Street.

After visiting Sandown, Julian was soon back in France, never to return. When Alice heard that Julian

was missing in March 1918, a relative says that she attempted suicide by jumping into the sea from

Sandown pier. Then in the June Quarter of 1918, Alice died, a twenty-seven-year-old victim of

tuberculosis. She was buried at Christ Churchyard, Sandown, shown below.

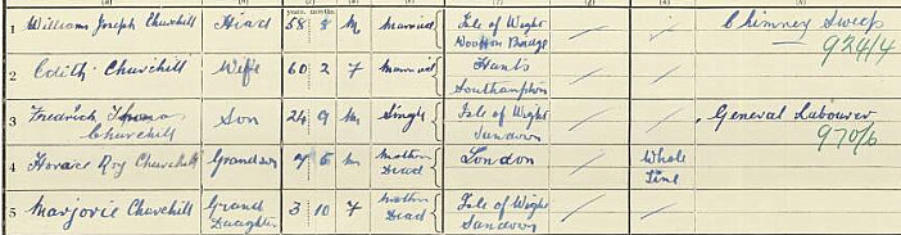

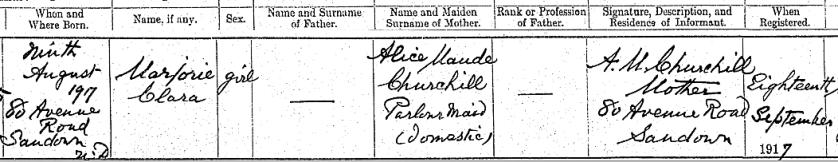

But there are more details of Alice’s life to be told. The 1921 census (dated 18 June 1921) was

consulted. At the time of the census, Alice and Julian’s infant daughter, Marjorie, were being cared for

by her grandparents, William and Edith Churchill at 80 Avenue Road, Sandown:

Here we see confirmation that Marjorie’s mother had died, and included in William and Edith’s

household was another grandchild whose mother had also died - Horace Roy Churchill, who was born

in London seven years and five months previously. The Index of Births pins down the area as Hackney

RD, M-sex and the time of the event being in the first quarter of 1914, probably January.

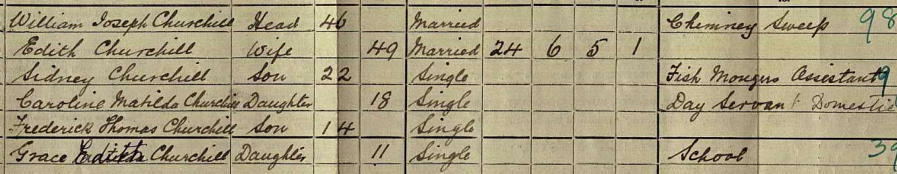

The 1911 census, shown below, informs us that William and Edith had six children, one of whom had

died before 1911. Apart from Alice, there were two other daughters, Caroline and Grace, and both were

certainly alive in 1921. So, Horace was Alice’s first child, born two years or so before she and Julian

had met.

It was a kind and generous act for William and Edith (who were around sixty years old) to accept the

responsibility of caring for young Horace and the orphan, Marjorie.

The only event in Marjorie’s life in the years that followed I can find was that on 1 June 1929, the IoW

Education Committee offered her a place at Sandown Secondary (Grammar) School either as a minor

scholar or a fee-paying pupil:

During the first quarter of 1935, when she was aged eighteen, Marjorie married David Frank Smith on

the Island. Four years later, The Register revealed that David was born on 16 February 1916 and was

employed as a carpenter and joiner.

Marjorie Clara (nee Churchill) Smith

Marjorie had four children and then grandchildren were born. She and David bought the Parkbury

Hotel (below) at Sandown on the A3055 in the 1950’s and sold it in the 1970’s when they retired.

It is not my intention to provide details of Julian and Alice’s descendants. They may be found

elsewhere in the public domain. However, we should review the reasons for believing that Marjorie

was Julian’s daughter:

1) The DNA evidence. All other primary sources of proof of descent are based on paperwork such as

birth/baptism, marriage and census certificates and entries. In each case, the registrar or clerk only

wrote what he was told - in other words, the ‘proof’ is merely hearsay. There are a myriad examples of

errors due to deliberate deceit or ignorance by folk who have made false statements to the authorities.

But to establish the identity of Marjorie’s father, there are several close DNA matches between one of

Julian’s grandchildren and living members of the Gribble and Royds families. This DNA evidence is

incontrovertible - it cannot be successfully challenged.

2) One of the hardest parts of confirming DNA evidence is to place two parents at the same location

and at the same time. In the Paul Oppé archive at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art,

there is a collection of letters exchanged by Norah Gribble and her friends and neighbours, the Oppés.

From the evidence of Nora’s hand, Julian was on the Island shortly after 16 November and was

shipping out to France on 5 December 1916. This is within the time-frame of Marjorie being conceived.

3) The physical evidence of Norah Gribble’s extraordinary auburn hair-colouring trait being passed

down to Majorie and her descendants. That she inherited this can be seen from her photograph shown

above. I have also seen photographs of another descendant who has this same feature.

4) There is the oral testimony of one of Julian and Alice’s surviving grandchildren which confirms that

she believes that Marjorie was their child. Incidentally, she has a copy of The Book of Julian.

Finally, questions might be asked: Did Julian’s family know about the relationship between him and

Alice during the early twentieth century? Do they know today, in 2023 - did they sit through the re-

dedication of the window in St Martins, Preston knowing what had happened? Did Julian know that

Alice was pregnant and later that she had given birth to their child?

Probably Norah was unaware of what had happened. Her son, Philip Gribble, wrote that she was

‘convinced that her family were beyond reproach, an outlook that made her intolerant of even minor

faults’. She also was intensely religiously devout. But Philip also commented that he believed his

mother had psychic powers such as a gift of prophecy - although the example he gave of this is

tenuous. If this was so, might Norah have ‘sensed’ something about what had happened - but this is to

accept an entirely different dimension.

Knowing as we do Alice’s family background, and that she was an unmarried mother, possibly implies

that Julian would not have told his relatives about his partner. Yet there is a legend of a gold bracelet

being sent to her as a gift - though the identity of its sender is unknown. It might have been Julian.

Here we are dwelling on Julian and his family, but we should not forget Alice and her feelings. There

can be little doubt that her alleged attempted suicide which followed her belief that Julian had been

killed displays the depth of her emotions for him.

The reaction of Julian’s present-day relatives and interested people to the possibility of Julian having

offspring indicates that even now his family are unaware what has been described here. My

suggestion was ‘surprising’ and passed on only ‘diffidently’ - which is quite understandable.

There are two reasons for disclosing these details of Julian’s life. Firstly, a century later there are

several descendants from him and Alice who have the right to know their ancestry - and if they

research the Gribbles and Royds family histories, they may well feel proud of their forebears. Julian’s

grandson wrote, ‘My view on any connection we may have with any of our ancestors is that facts are

facts, we are all the product of genealogical history which happened way in the past, the judgements

of who did what with whom are not for us or others to make, let's tell it how it is.” Secondly, many

Preston villagers will be aware of Julian and Norah. Their church has memorials devoted to them and

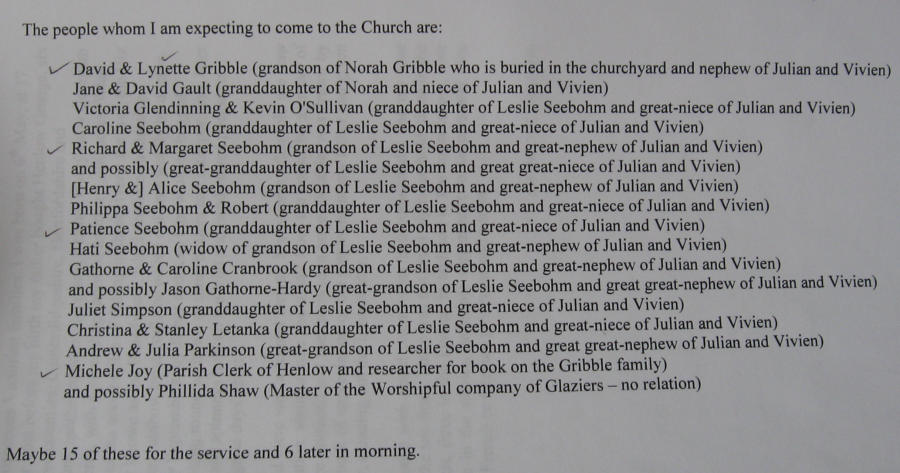

there was local interest in the re-dedication of a window in the church in 2007. Below is a listing of the

people expected to attend the service. The Book of Julian has recently been mentioned in the Parish

newsletter and is available to anyone who wishes to read it in the village. They will be interested learn

of this discovery.

Alice’s death certificate satisfyingly confirmed all of the details passed on by her grand-daughter. She

died at home; she had contracted TB, with the complication of ha(e)moptysis (ie coughing up blood)

and she had worked as a hotel waitress. The informant was her sister, Grace Edith Churchill.

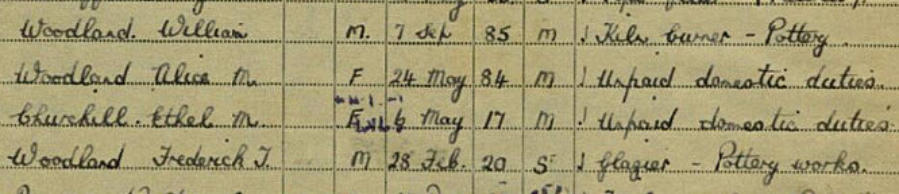

Finally, to tie up one loose end, here are brief details of Alice’s son, Horace Roy Churchill’s, life.

He married Ethel May Woodland during the June Quarter of 1937 in the Poole Registration District.

The 1939 Register shows Ethel with her family at 142 Blandford Road, Poole. Presumably Horace

was involved in some wartime activity.

The couple had four known children: Phyllis M Churchill (born 9/1936 Bridgwater, S-set RD),

William H (12/1939, Poole RD), David R (9/1947, Poole RD) and Carole A (9/1952, Poole RD).

Between 2003 and 2005, Ethel was living at 3 Colchester Way, Weymouth, which is part of a complex

of OAP bungalows. She died in the December quarter of 2005.

(Acknowledgements: I am grateful to John Medland author of ‘A Soldier’s Story’ and the publishers,

IW Beacon Ltd, for their kind permission to reprint the article about Julian Gribble. I am also grateful

to webmaster Nigel Watts for allowing me to include extracts concerning Julian and Philip Gribble)

A copy of Norah Gribble’s book, ‘The Book of Julian’ (1923), devoted to Julian, was recently held by a

Preston villager and made available to interested folk through the local parish magazine.

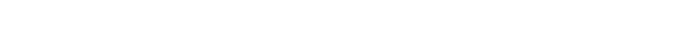

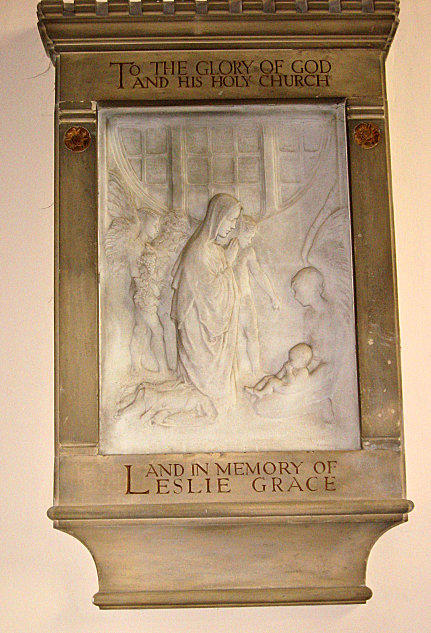

Inside St Martins are wall plaques in memory of Mrs Seebohm and Julian Gribble. There is also a

stained-glass window in the south chancel memorialising Julian Gribble which was designed by his

sister, Vivien Gibble.

One cannot help but notice how the news of Norah’s death and funeral was muted and stifled -

especially when one considers the social status she undoubtedly enjoyed and her circle of friends

and family. Apart from the report above I can find only one notice of her death in the Biggleswade

Chronicle (which included the area around Henlow, Beds.) and the announcement of her funeral

arrangements in The Times.

Norah was buried with her daughter, Leslie Seebohm in St Martins, Preston graveyard on 12 March

1923. She gave instructions to the effect that she should be buried close to the window dedicated to

him and also near her daughter’s grave. She would then have had the sense of being close to him.