Preston Fair - Sheep and Fun-fair

The origins of the fair at Preston Green are unknown. The Victorian History of Hertfordshire gives a

detailed breakdown of when, and by whom, the fair at Hitchin was granted but makes only a brief

reference to Preston Fair stating that, ‘There are also two fairs at Preston held on 1 May and 23

October (in 1816) and later on the first Wednesday in May and on the Wednesday before 29

October’.

Preston’s fair was probably not held between 900 and 1516 AD as it is not included in the Gazetteer

of Markets and Fairs in England and Wales for that period. A letter from Ralph Radcliffe of Hitchin

Priory to his brother, Edward, dated 17 October 1734 is the first historical allusion to the fair at

Preston:

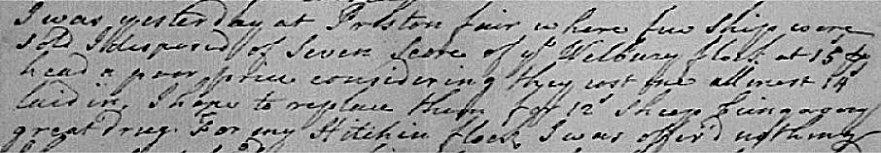

The letter reads in part: “I was yesterday at Preston Fair where few sheep (?) were sold. I disposed of

seven score of my Welbury flock at 15 shillings a head - a poor price considering they cost me almost

14 shillings laid in....For my Hitchin flock I was offered nothing.”

Further information about Preston’s fair is provided by Owen’s New Book of Fairs which in 1816

identifies Preston’s as a sheep fair.

To put the fair at Preston into its local context, there were thirty fairs held in the whole of Hertfordshire

in the early nineteenth century - but only six sheep fairs. These included one at Hitchin - which was

held on Easter Tuesday and Whit Tuesday but in 1834, it changed from a sheep fair to a wool fair -

and another at Pirton which is about seven miles north-west of Preston. The Pirton fair was held on

the fourth Thursday after 5 April and on the fourth Thursday after 10 October - thus, both of Pirton’s

fairs followed Preston’s fair by a few days.

Sheep fairs at Preston were held twice a year until at least 1864 as they were still being advertised in

local newspapers. But by 1873, from the evidence of comments in the Preston School log book, it

was no longer a sheep fair but a fun fair - and held only once a year, in October. The last Preston fun

fair was held in the autumn of 1914.

Sheep farming on the Chilterns and at Preston

The small cluster of sheep fairs around Hitchin indicates that sheep farming was an important form of

agriculture in North Hertfordshire. Nigel Agar in Behind the Plough writes of the high chalk of the

Chilterns, ‘the vast wind-blown fields were less likely to be cultivated for arable crops than they are

today. Much of the hill country was reserved for sheep that grazed on the short cropped downland

where shepherds lived a lonely life tending their flocks....after sheep had been folded on the land to

feed directly on the root crops, barley was sown in the spring.

‘Shepherd in melting snow with Offley Holes in the distance’ by Samuel Lucas

The first extant historical reference to shepherds around Preston is of my greatx2 grandfather, Joseph

Currell (1800 - 1863). During a dispute about the parish in which he and his family should be settled,

Joseph stated that in 1825 he ‘let’ himself to George Roberts at Kings Walden Lodge, lodged at his

master’s house, served him for six years and received wages of ‘five shillings a week and five

pounds’

The censuses of the nineteenth century provide snapshots of Preston farms and their shepherds as

follows:

1851 -Thomas Smith (Temple Farm); Thomas Cotton (Home Farm, on the Hitchin Road);

Joseph Currell (farm not known)

1861 - John Shaw (Poynders End Farm?), John Jenkins (Preston Hill Farm); Joseph Currell

1871 - John Shaw; William Freeman (farm not known)

1881 - John Shaw; Thomas Fairey (Preston Hill Farm)

1891 - Thomas and son, George, Fairey

1901 - Henry Young, Arthur Ayres and Robert Crawley. (Farms not known)

1911 - no shepherds noted in census.

This information is not comprehensive. Newspaper reports tell us that Benjamin Hill at Pond Farm

had a shepherd boy in 1843 and that Mr Wright of Preston Hill Farm had a shepherd in 1842.

What can be said from this evidence is that in the nineteenth century, at least five farms at Preston

had enough sheep to warrant a shepherd.

As well as local sheep, those brought to Preston Fair could have been augmented by flocks from a

radius of up to twenty-five miles. The Oxford Companion to Local and Family History observes, ‘For

the great majority of fairs vendors rarely travelled more than twenty to twenty-five miles. Most of the

rural fairs were modest in scale.’ It may be surprising that sheep might be driven such distances to a

fair, but it should be remembered that a fourteen-year-old boy drove nineteen of Rose Beckford’s

sheep around thirty miles from Offley Holes to London in 1799! The only hint from newspapers of the

distances travelled to attend Preston fair is that in 1850 a farmer from Knebworth travelled around

seven and a half miles to the village.

So twice a year, Preston was invaded by shepherds, their sheep dogs and hundreds, or more likely,

thousands of sheep - ‘their numbers creating a singular and remarkable appearance’. The local lanes

would be have been clogged with flocks; the air would have been filled with their plaintive bleating

and everywhere - on its roads, its verges and its Green - sheep droppings would pollute and foul the

village. In wet weather, the highways and byways would be awash with an offensive, stinking olive-

green slurry

Perhaps some of the flavour and effluvia of Preston’s sheep fair is captured in Thomas Hardy’s poem,

A Sheep Fair:

Why did the sheep fairs at Preston cease being held? Probably because in common with many other

fairs, the supply of local sheep dwindled. An unexpected likely reason for this at Preston was the

emergence of the railway - in 1851, the Royston and Hitchin line was opened. Among the “good’s”

that could now be transported the thirty miles from London was the by-product of the capital’s many

stables - manure. This could be spread on the infertile fields of the Chilterns and so crops now could

be grown that were more lucrative for farmers than grazing sheep.

Preston’s funfair

In around 1870, the Preston Fair evolved into an annual funfair. The village children were allowed an

afternoon’s holiday from school. It was an highlight of their year for which they saved for weeks.

Rather than attending school, they gathered acorns which were sold as pig fodder to have some

pennies in their pockets.

We have no descriptions of the fair at Preston so perhaps a detailed report by Edwin Grey of the fair

at the nearby village of Harpenden will paint a picture of festivities. The fair was eagerly anticipated

especially by the children and young people, not only of the village but also the folk living in the

surrounding countryside. All local residents, cottagers and the well-to-do made a point of attending at

some point. There was much rollicking – innocent fun – into which everyone seemed to join.

Youngsters began saving their ha’pence for a long time in advance and were content with sixpence or

even four pence in their fists.

The stalls featured roundabouts, swings, shooting galleries, show booths which were the most

popular attractions especially if bespangled young ladies danced on a platform outside or a clown or

two acting their tomfoolery. The roundabout was pulled by a horse – and a bell sounded to end the

ride. The shows were well patronised. Crude drawings and pictures enticed people to gawp at

astounding freaks of nature and if the show didn’t quite live up to the hype, it was all part of the fun.

There were performing ponies, birds, mice and even fleas. The ‘Baked Pear Vendor’ was a popular

stall – a neat, little old lady in a black dress, poke bonnet, spotlessly white apron and little shawl over

her shoulders who doled out saucers full of stewed pears. In the evening in 1873, a gypsy fiddler was

playing for dancers in the Red Lion, Preston. After enjoying ‘all the fun of the fair’, the children were

over-excited and overtired . One Preston School log book entry from 1898 comments ‘Many stayed

out so late that they were too tired to come (to school) the next day’.

After 1914, the only evidence of Preston’s sheep fair history were the wide paths that criss-crossed

Preston Green - visible in so many photographs (see below) - which were ‘said to have started as

sheep tracks’.’ These paths were “filled in” around the time that new saplings were planted on the

Green in the early 1950s.

The day arrives of the autumn fair,

And torrents fall,

Though sheep in throngs are gathered there,

Ten thousand all,

Sodden, with hurdles round them reared:

And, lot by lot, the pens are cleared,

And the auctioneer wrings out his beard,

And wipes his book, bedrenched and smeared,

And takes the rain from his face with the edge of his hand,

As torrents fall.

The wool of the ewes is like a sponge

With the daylong rain:

Jammed tight, to turn, or lie, or lunge,

They strive in vain.

Their horns are soft as finger-nails,

Their shepherds reek against the rails,

The tied dogs soak with tucked-in tails,

The buyers’ hat-brims fill like pails,

Which spill small cascades when they shift their stand

In the daylong rain.