Emily Soldene - her story

‘Emily Soldene was a singer and for a couple of nineteenth century decades, a star among

stars on the English-speaking stage’ – thus, Kurt Ganzl introduced the subject of his

exhaustive biography.

Emily Soldene was probably born on 30 September 1838 at Clerkenwell,

London. Her mother ran a business as a straw bonnet maker and the family

was living at Finsbury, London in 1841 and 1851.

Taking her later writings at face value, Emily had a nurse and a governess, she

learnt to play the piano and ‘was educated at Mrs Freeman’s academy’. She

also saw the ballet, Giselle, as a teenager.

She married John (Jack) Powell, a law clerk, on 17 March 1859 at

St Marylebone, London. He was the son of a news reporter who worked with

Charles Dickens. Emily wrote, ‘(I) ran away when I was very young but old

enough to know better’, ‘my parents were against the match’.

The inauspicious setting of the wedding is captured in another recollection: ‘at my wedding, the best

man, I think he was the pew opener, could not be trusted with the precious thing (her wedding ring)’.

Powell became her treasurer and acting manager for more than a decade. The couple had four

children: Kate Elizabeth (born 10 March 1860), Ellen Clara (8 June 1861), Edward Charles Solden

(27 February 1863) and John Arthur (12 September 1867).

‘When I was quite young, I heard Santley (the “ultimate English baritone of the Victorian age”). Never

shall I forget it. I felt I would give the world to sing, to be an artist’. Emily approached William Howard

Glover ‘who considering it to my advantage to hear as much good music as possible, sent me to one

or other of the opera houses every night of the season. There, my taste was formed and nourished by

the greatest artists of the day’.

Her first appearance on the dramatic stage was in a portion of Il Trovatore in January 1865 during a

concert at Drury Lane. The Daily Telegraph reported, ‘ Emily Soldene...has a dramatic stage

capability of high order...she possesses, too, the physical advantages of a handsome face and a tall,

well-proportioned figure. In voice, she is almost equally well gifted and she has evidently been

carefully trained.’

But Emily was leading a double musical life: by matinee she was Soldene, the classical opera singer;

by night she was Miss FitzHenry, the music hall songstress guided by her friend and mentor, Charles

Morton. She enjoyed adulation and growing popularity in the music halls: ‘Miss FitzHenry’s songs are

received with the most uproarious applause’. She had ‘fervent style and power’ and ‘completely

electrifies the audience’.

A crossroads was looming in her career. In reality the choice was relatively simple: the music halls

paid regularly and the concerts, spasmodically. She had also split with Glover after serving her

indentures and the final deciding factor was the emergence of a new rage from France – opera boffe

– to which Emily was particularly well suited. She enjoyed that most fortunate of juxtapositions: being

the right person, in the right place, at the right time.

Opera bouffe was a musical form which combined ‘the sparkle of French wit and

music with the elegance of opera comique and the inoffensive of the choicest

English burletta (a farcical play set to music)’. It was ‘sparkling, spicy,

spectacular’ entertainment. Its flavour may be captured from two reports: ‘Sweet

innocence. A little girl went with her mother to a Soldene concert. When that

lady and the full chorus appeared, the little girl...looked at them a moment then

said, “Mama, are those women ready for bed now”’. Writing later, Emily recalled

seeing a performance of Chilperic. ‘The ballet was on...the sort of thing one

might take one’s mother...when suddenly, “Bing-bang-boom” on the drum and

cymbals, and to everyone’s astonishment, four-and-twenty legs shot out...as far

as possible and as undressed as possible, and before we had recovered from

this severe shock, four-and-twenty other legs shot out...just as far and just as

nude. The dresses were worse than deceptive, they were slit up to the waist...’.

This musical form was embraced by Emily using her vocal and comedic talents

– ‘her voice, her vitality and her magnetism first found their perfect material’.

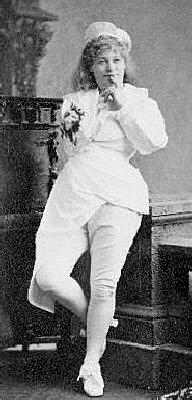

(right: Emily as Chilperic)

From 1869 to 1871, she starred in productions in London and the provinces

of: The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein (as the Duchess); Little Faust (as

Chilperic) and Genevieve de Brabant (as Drogan, pictured left). The

breakthrough came when John Russell was searching for a replacement

Grand Duchess in a smash-hit show and selected Miss FitzHenry; except

that she was killed-off and Emily Soldene, resurrected.

Glowing reviews were written of her performances in London and the

provinces: ‘Miss Soldene brings both vocal and histrionic powers of a

conspicuous order...and infuses an immense amount of vitality into her

portraiture...’. ‘...It would be difficult to name any actress who could better

portray the passions, emotion, weakness, hauteur, regal dignity and esprit of

the German beauty. Her dresses are magnificent and her deportment

graceful, queenly and captivating.’

Emily sailed from Britain to conquer the Americas in 1874 -75. By now she

was managing her own repertory troupe. New York capitulated: ‘I was found

to be “magnificent”, “magnetic (I am afraid they also said, ‘massive’)

possessing vim, a grand voice and...knew what to do with it’. Soon everything ‘Soldene’ was the rage.

‘Soldene’ stockings, hats, gloves, fans and coiffure.

‘But the greatest sensation was the “Soldene” girl. Never had been seen such girls, real girls with fine

limbs, complexions nearly all their own, beautiful creamy white skins, figures perfect...“The Boys”

simply went crazy over this crowd of imported loveliness’.

Following two months of huge success at New York, Emily took her troupe onto the (rail)road. For five

months from January to May 1875, America was criss-crossed with five-day shows at Philadelphia,

Boston, New Orleans, Chicago and Canada, to mention a few of the towns invaded. ‘Miss Soldene is

genial in manner and has a pleasant face, one feature of which, according to physiognomists,

indicates a prodigal generosity. She has a powerful voice, well trained, and very effective on

stage...(her) forte is jolly extravaganza with music, grace and symmetry as lib.’

After a triumphant return to Britain, Emily’s show embarked on a tour of England’s major towns from

July to October 1875 which drew similar rave reviews – the magic was still there – but it wasn’t quite

the triumphant procession of earlier tours. Newly-introduced shows were not as popular as the old

favourites, the first signs that the appeal of Emily’s version of opera bouffe was beginning to dull.

Then, it was back to America for a gruelling tour from December 1876 until July 1877.

America now exhibited a fascination with Emily’s mouth! ‘Hers is a long,

square-cut mouth, but not only is it phenomenal in size, but also

phenomenal in its workings. It is capable of more posing and posturing

and contortions than any other similar orifice in the world. It does not

simply open and shut; it chases the other features all around the face...’

Australia was Emily’s next port of call. The entourage made their debut in

Sydney on 15 September 1877. This engagement also providentially

provided a record of its receipts for one performance. There were 1,456

customers who paid £166 9/- of which almost £100 was passed to the

tour. In England, the normal box office receipts were between £30 and

£40.‘The Soldene troupe is an unparalleled success...All parts of the

theatre were densely crowded. Mlle Soldene received a magnificent

ovation.’

Back in England, in 1879, Emily introduced Bizet’s Carmen to the provinces for the first time. ‘Miss

Soldene as the cruel and faithless Carmen sang and acted with appropriate dash, spirit and

recklessness and elicited repeatedly the heartiest applause...’. ‘It was generally conceded that my

Carmen was a good one. I had a natural turn for the tragic’.

From the ‘tragic’ to tragedy: Emily was reported as being taken seriously ill while in pantomime at

Glasgow in January 1880. This was clearly a smokescreen. Her husband, Jack Powell had a severe

stroke and became an invalid. He was consigned to the salty breezes of Bognor in the hope that the

seaside might kick-start a recovery. His nurse was Naomi French from Preston, Herts.

Emily needed to work and another long tour of Britain began, running from March to October of 1880.

The ‘notices were good and appreciative, but they are no longer thrilled as they had been in the days

when...their kind of entertainment was fresh and new’. Emily was a fondly loved old favourite rather

than a bright new star. ‘The shiniest shine was gone’ for a performer in her eleventh year as a star of

opera bouffe.

The Atlantic was crossed again in 1880. Now the reviews faltered: ‘The Soldene company appeared

last night in a mangled adaptation...The music was beyond their capabilities...there is a pitiable lack of

both dramatic and vocal talent.’ It was an ‘old show with old costumes, old props, a depleted

company, colds, no money and pretty low morale’. Emily decided to go sleighing, became indisposed

and was savaged: ‘it was the most wretched performance of that opera ever given in

Syracuse...Soldene, fat and forty...her voice is broken and unmusical’. She played numerous dates

across America from November 1880 until June of the next year but received rotten notices.

This period, between 1880 and 1881, were the lowest point of Emily’s life. Not only was there the

dreadful American tour, but she also became a widow: while she was performing at Crystal Palace,

Jack died at Bognor on 14 September 1881 from ‘paralysis’ likely induced by a further stroke. Emily

was forty-two, husband-less with four children and, as far as the stage was concerned, she was

yesterday’s heroine.

Yet back home, her stock remained high and the troupe was booked on a tour from February to

December 1882 beginning at Dundee and ending at Newcastle – the ‘longest and densest tour’ they

ever undertook.

Undaunted by her last American experience, Emily was back in 1883 for

a further unsuccessful tour which, together with an experiment in theatre

management, depleted her funds. She appeared at Oxford. A critic wrote,

‘We hardly know how to convey to Madame Soldene with sufficient

delicacy that there is a period at which it is wise for an artist to rest on her

laurels...the spectacle of an elderly lady..twitching her petticoats in the

regular opera bouffe manner was so unutterably sad and ghastly to

behold that a number of persons rose from their seats in shocked silence

and quietly left the theatre’.

Distant Australia beckoned again in 1892. Her tour, though, was another

financial disaster which wiped out Emily’s depleted resources – but there

was a silver lining in the cloud! She left the stage and, living in Sydney,

began a new career as a newspaper columnist for three years from 1892

to 1895. The reason she gave for this new direction was basic: ‘Self preservation....I was paid for the

very first lines I ever wrote’. She began with an ‘eloquent tribute to myself’.

While ‘down-under’, Emily, the fledgling writer, started work on her first novel, Young Mr Staples. It was

a sensational tale of ‘a girl done, or gone, wrong; of her tortured life and super-tragic end’. The book

showed that Emily ‘had writing skills aplenty’, its humour was an improvement on its sentiment and the

finale was ‘simplistic’. The critics were luke-warm: it was ‘not without merit’ and the writing had more

‘vitality than art about it’. Another added that it was proof that Emily ‘is not only alive, but that she is

kicking’. The book probably did not sell well.

When she left the Antipodes, a paper wrote, ‘Not only in opera has Madame Soldene achieved fame

but in the literary life of Sydney her journalistic career as a musical and dramatic critic created quite a

sensation for the brilliancy of her writing and the complete knowledge of her subject’.

Emily continued as the music and drama critic for the Sydney Evening News. Then, came her literary

tour-de-force: the innocently titled, My Theatrical and Musical Recollections. ‘Emily’s memoirs made

more of a stir than any such book in living memory.’

Of her revelations it was written, ‘She has had the good fortune to know many of those whom the

world calls smart people...One and all she gives away...Now not a few of them are statesmen, judges,

peers...Relentlessly she reveals to the world what she knows in their lives...If the conditions or the

results might justify proceedings in the courts, divorce or other, all is told...Nobody is spared, not even

those in the highest position.’ Her autobiography sold well: ‘since its frank revelations about the gilded

youth of statesmen and fathers of family men like Lord Rosebery and Lord Dunraven began to be

known, there has been a great rush for the book.’ It was a full scale winner!

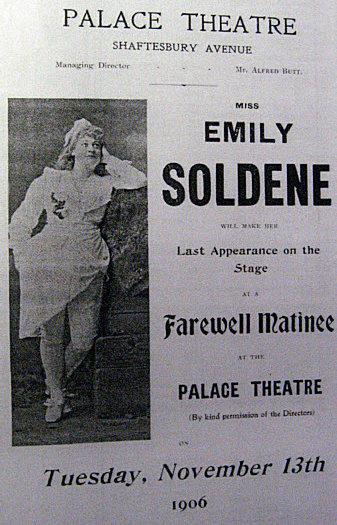

A nostalgic farewell matinee concert for Emily was arranged for 13 November 1906 at the Palace

Theatre, Shaftsbury Avenue. ‘For a lady of sixty (68 actually!), Miss Soldene sang remarkably well’.

The concert raised £800. Emily gushed, ‘My career has been a chequered one and here’s the end of

it – only it’s a different sort of cheque’. (A nearby gentleman took the hint!)

Emily fell ill. ‘Bad times – horrid times. Cruel times, narrow escapes, long

journeys, travelling to the Beyond – to the Borderland.’ In November, 1911

she underwent an operation – evidently serious as she wrote to her

Australian readers, ‘Au revoir...if all does not go well, it means “good-bye”’.

Her apparent recovery was celebrated.

Emily died during the night of Sunday, 8 April 1912 at her lodgings in

Bloomsbury. Although she had been ill, her demise was unexpected. She had

recovered from her operation, but suffered a heart attack. Underlying her

condition, though, was diabetes. She was interred at Shirley Cemetery,

Surrey with only two family members and very few ‘theatre people’ present.

She left a small net estate of £810 which was bequeathed to her son,

Edward.

Kurt Ganzl, as he drew the final curtain on his 1,551-page work devoted to

Emily, wrote ‘...I reckoned she was thoroughly worthy of what must surely be

in any case the biggest theatrical biography of the year. Of the era, of the

century. Heck, maybe of all time, for all I know.’

(I am grateful to Kurt Ganzl for his generosity in providing the photographs, allowing his biography to

be condensed and checking the completed epitome)