The cottages of Preston - an overview to 1920

An Act of Parliament in 1589 meant that cottages in England could only be built if they had four acres

of land assigned to them. This Act was repealed in 1775. There were two other factors that impacted

on the housing situation at Preston: (1) Local farm labourers and tradespeople together with their

families had to live somewhere. (2) Weekly wages of labourers were low (around 10/- a week in the

early 1800s), which affected how much rent could be charged. This made buying or building new

cottages an unattractive project for speculative landowners and businessmen - buying land and

building a cottage for a return of about £5 pa in 1894 made the construction of new homes a poor

investment. As a result, local house building did not keep pace with demand.

In 1800, all of Preston’s cottages were owned by tradesmen (such as the Joyners and the Pedders),

labourers (many of whom inherited their properties) and a few landowners (including Thomas

Dashwood). Surprisingly, none of the homes were owned by the Dartons of Temple Dinsley. To

maximise their income several owners divided their property into two or more homes, thus increasing

the rent they received, while reducing their tenant’s gardens where produce might be grown.

The evolution of one cottage and garden at Back Lane provides an example of this process of

maximising rental income. It was ‘formerly one cottage’ which at ‘sometime past was divided into two

dwellings’. Two more cottages were built in the garden of the original cottage. Four households were

thence living in what had been one cottage and garden. In 1816, a Hitchin grocer bought the plot of

four dwellings. He sold them to Elizabeth Darton of Temple Dinsley on 31 March 1830 for £130.

Following Thomas H Darton’s death in 1858, his son William Henry Darton acquired this holding.

When William sold Temple Dinsley, he sold the four cottages as a separate lot to the illiterate Preston

labourer, Henry Jeeves, on 25 March 1874 for £125. In turn, Jeeves sold the four tumbledown homes

to Ralston de Vins Pryor for just £97 10/- on 27 June 1899. When the Inland Revenue Survey was

conducted in 1910, all four dwellings were assessed as being in a poor condition. They had been

demolished by 1916.

The Darton family (Joseph jnr, his wife Elizabeth and their son, Thomas Harwood Darton) pursued a

deliberate policy of buying local cottages as they became available: Back Lane (10 cottages); north

side of Church Lane (9), Crunnells Green/School Lane (6) Hitchin Road (2) and Preston Green (2).

The result was that from owning no cottages in 1810, when the Dartons sold the Temple Dinsley

estate in 1873 they were landlords of ‘nearly the entire village...about forty cottages’.

Even with hindsight, it is difficult to say why the Dartons bought these homes. Was it for a measure of

control of the hamlet and its inhabitants by the Lords of the Manor? Was it a philanthropic gesture -

despite the run-down state of the cottages? Did the Dartons consider them to be an investment - a

cottage which cost £100, produced an income stream of about 5% pa, less repairs? Probably, it was

for a mix of all three reasons that the family bought so many properties.

One might ask, why did the Dartons build only one new houses in the hamlet? Despite their windfall,

possibly there was a lack of funds with which they could finance the construction of new homes as

their fortune was divided among several beneficiaries according to the terms of the wills of the

deceased landowners. They were continually seeking to let Temple Dinsley - and at least two of their

tenants spent large sums of money improving the property rather than the Dartons having to pay

huge bills. Then there was the undoubted ill-health suffered by male Dartons (followed by early

death) to be considered. Did this impinge on their ability and/or desire to care for the plight of the

community over which they lorded?

The reality of their portfolio of run-down dwellings becomes even harder to understand when Thomas

H Darton snr’s will stipulated that his surviving wife should, at her own expense, ‘keep (her inherited

properties) in good, substantial and tenantable repair’.

A further mitigating consideration is that soon after the Dartons inherited Temple Dinsley, England

was embroiled in war with France from 1792 until 1815 - and immediately after this was a time of

economic recession.

The stark message of history is that if the Dartons had demolished some of their mouldering

properties and built new replacements, their income from rents would not have increased significantly

and the construction programme would have cost them thousands of pounds. Take as an example

the six houses along School Lane, all of which were acquired by the Dartons during the nineteenth

century but were in a ‘poor state’ of repair in 1910. Ten households lived there, paying ten lots of

rent. If these were pulled down and replaced at some cost, the income from them would have been

about the same as was being received. In the final analysis this apparent lack of consideration for the

plight of their tenants points to a possible deficiency of social conscience on the part of the male

Dartons who were happy to have their own property improved by others, while their own tenants lived

in squalor.

After becoming the hamlet’s main landlords in 1873, the Pryor family continued the policy begun by

the Dartons of buying-up old properties. But as so many properties were assessed as being in ‘poor

condition’ in 1910 during their tenure, to what extent did they too accept their responsibility as

landlords to repair and maintain their holding? After 1910, many of these homes were demolished.

The detailed Topographical Map of Hertfordshire (1766) shown above gives an impression of the

cottages at Preston of the time - although, judging by the way the farms are portrayed, some

outbuildings have also been included. Also, homes that adjoin other homes are shown as one

rectangle.

Nevertheless, an informative picture is given of Preston’s housing stock - it is a view that hardly

changed for 134 years between 1766 and 1900 because I believe only three new cottages were

erected in the hamlet during this period: Kenwood Cottage (built 1861 - 1871) and The Laburnums

(1891 -1901) at Preston Green and also a ‘newly erected cottage where a barn had previously stood’

on the north side of Church Lane, which was constructed in 1811.

This lack of house building had serious implications for Preston folk. Firstly, as time moved on, their

homes (built pre-1766) became more and more run down and unfit for habitation. The nineteenth

century censuses recorded an increasing number of empty cottages in the hamlet - not because of a

decrease in demand, but because of their tumbledown condition which culminated in thirty-six

cottages (approximately half of the housing stock) being pulled down and replaced by thirty-three new

homes between 1905 and 1925 - not to mention those demolished before 1900, such as the six

derelict cottages along Hill Farm Lane.

The second result of the lack of new houses in Preston was that although some cottages were

subdivided to increase the number of homes in the hamlet, several hundred children were born at

Preston during those 134 years. Most grew up and married but were forced to move away from the

hamlet because there were simply no houses in which they might live. From the evidence of the

censuses, my rough estimate is that every ten years between 40% and 60% of Preston folk moved

away from the hamlet! Many of these were young men and women. They left behind an ageing

population and several families living in overcrowded, insanitary conditions. Preston was “beginning

to rot from the centre”, as Nigel Agar once wrote. In 1901, Mary Currell, was living in a two-up-two-

down hovel beside Back Lane with seven children and grandchildren, while my grandparents, Alfred

and Emily Wray, with their eight children, inhabited a home with a ‘lamentable’ three rooms at

Chequers Lane. Both houses were said to be ‘in poor condition’ in 1910.

Temple Farm

Home Farm

Preston Farm

Castle Farm

Pond Farm

Red Lion

Chequers Inn

Back Lane

Hill Farm Lane

Crunnells Green

School Lane

Preston Green

Hitchin Road

Chequers Lane

Butchers Lane

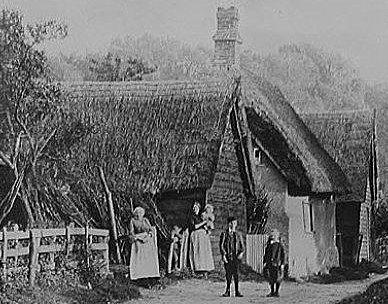

Typical Preston cottages in the nineteenth century

Three examples of common Preston homes are shown above. Roofs were thatched or adorned by

small, red/orange tiles or slates. Walls were mainly constructed of brick - not flint which was locally

available. This might be surprising until we remember that ‘brick earth’ was dug around Preston and

that there were brickworks in Hitchin. Interior walls of older cottages were of daub and wattle (one has

been exposed at Rose Cottage, Butchers Lane). Barns were made of overlying clap-board, such as

can still be seen in the village today

Why were only three new homes built at Preston between 1766 and 1900?

Acts of Parliament to improve housing conditions of the labouring classes in the late 1800s

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, central government began to react to the promptings of

social reformers to alleviate the atrocious conditions in which its non-voting people were living -

particularly in the slums of towns and cities.

This spawned The Artisans and Labourers Dwelling Improvement Act (1876) which for the first time

empowered local councils to take out loans to compulsorily buy up areas of slum housing in their

authority area in order to clear and rebuild. This was followed by The Housing of the Working Classes

Act (1890), which allowed councils to buy up surrounding agricultural land and vacant urban land.

Now the plight of country-folk living in squalid conditions might be addressed.

A contemporaneous local newspaper article in February 1894, Labouring Classes Housing, provides

some illuminating comments about the housing situation in many Hertfordshire countryside villages.

1) Owners of large rural estates found cottage property a very expensive possession. That their

labourers, after amassing savings, could get cottages somewhere else and relieve them of the

worry and expense connected with housing them was in the days of the unenlightened

conscience something to be thankful for.

2) Many of these rural cottages were built on small plots of ground filched from the waste, or on

other tiny plots of ground (for land has always been difficult to acquire) so small as to be utterly

incapable of forming a garden for the cottage and of growing vegetables sufficient for the

requirements of the occupant. The owners also, tempted to obtain as large a return as possible

for their outlay, in some cases sub-divided the garden and cottage so as to get two rents: in

other cases, they built another cottage adjoining the first and divided into two a garden which

was not nearly large enough for one cottage. In most cases the owners have been unable and

in many cases unwilling to spend any money on repairs with the result that the roofs, ceilings,

walls, floors not to mention the windows have been allowed to get into a shameful state of

repair. Of these cottages, many have only one bedroom: most of the rest in addition to the one

decent bedroom (if it can be called such) have a little make-shift bedroom on the landing at the

top of the stairs where often two or three sons and daughters sleep.

3) It appears a simple matter to condemn a house as unfit for human habitation and cause it to

be closed. But it must be remembered that there are a certain number of persons in the district

who must be housed and must be housed too within a reasonable distance of their work and

that a cottage pulled down or closed is not necessarily rebuilt or repaired and made fit for

habitation, because the rent which an agricultural worker can afford to pay does not make the

erection of houses, such as would in these days be considered fit to live in, remunerative as a

speculation.

4) There was an additional problem: The erection of cottages by the Statutory Authority not only

means a heavy burden on the rates but it is a burden which must be felt to be unjust and

iniquitous by most of the ratepayers. So why are additional cottages necessary? Simply

because one or more landowners have not on their own estates cottages sufficient to house the

labourers whose work is a necessity if their estates are to be worked as they ought. And it is

these landowners who would be specially benefited if cottages are built. In other words, the rest

of the ratepayers are to be taxed in order that these may be able to have cottages for their

labourers to occupy.

5) Suppose it was agreed that that every farm contained a sufficient number of labourer’s

cottages, how is this reform to be carried out? The impoverished land owner is not in a position

to do so. His burdens at present are greater than he can bear. What then would be the cost of

carrying out such a scheme as this and what might reasonably be expected of the landlord? It

may be taken for granted that an agricultural labourer in most parts of Hertfordshire is unable to

pay more than £4 10/- as a yearly rent of his cottage. Good cottages, and such only ought to be

erected, containing three bedrooms with sitting room and kitchen can be built for £300 a pair.

This is simply the cost of building and includes neither the value of the site nor the expense of

fencing.

6) Re: the exodus of the young country labourer to the large towns. How many such would

remain in the villages were the condition of their homes improved? And how many having tasted

the disappointments which await them in the large towns would gladly return but for the thought

of their overcrowded homes and the uncertainty of always finding work? But with more room

and decency in their homes and a garden of a size which would enable them to employ their

labour profitably should work on the farm become slack, many would be thankful to get back

once more to their native village.

7) There is another aspect of the question. At present the best girls in the families of labourers

go into service and having acquired habits of decency, comfort and self respect can seldom be

induced to return and settle down in the wretched cottages to which they were once

accustomed.

Preston’s housing stock gradually decreased between 1851 and 1891 from 82 homes to 77 cottages -

and in 1891, twelve cottages were unoccupied. The number of abodes was at its lowest in 1901 (64) -

which suggests that dwellings were becoming uninhabitable and were being demolished.

The situation changed dramatically after 1900 when thirty-six hovels were demolished at Back Lane,

Chequers Lane, Church Lane (overlooking the Green) and School Lane (from Crunnells Green

Corner to the Red Lion). They were replaced between 1905 and 1925 by 33 new homes, which were

financed by local landowners - James Barrington-White (two semi-detached homes at Crunnells

Green, 1905), Fenwick Harrison (eight - Holly Cottages circa 1918) Benedict and Violet Fenwick

(probably eight, including six - Chequers Cottages circa 1913), Douglas Vickers (three - bungalows

along School Lane) - and the Hitchin Rural Council (twelve Council houses built on the north-east

side of Chequers Lane.

All but four houses were built for habitation by labouring families. It’s possible that one of the cottages

at Crunnells Lane built by Barrington-White was intended to be occupied by the village policeman.

Crunnells Green House and the house at Lower Crunnells Green (on the corner with Back Lane)

were built by the Fenwicks for the estate manager of Temple Dinsley and the Temple Dinsley estate

bricklayer, respectively.

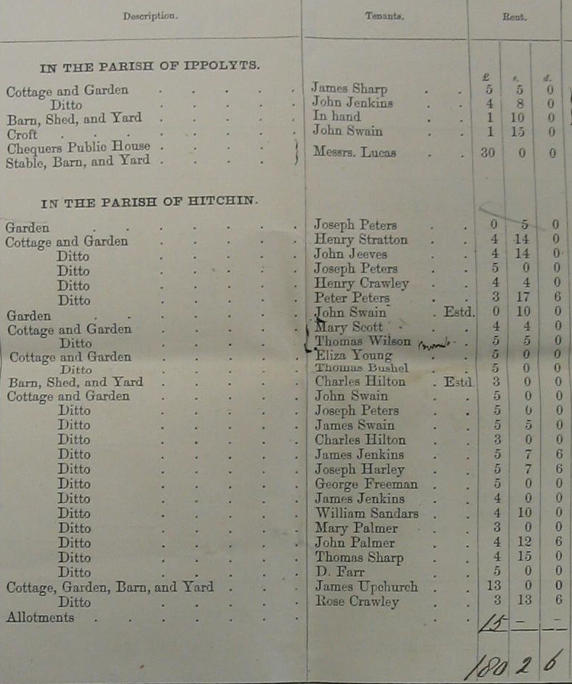

Rents of cottages at Preston in 1873

When the Temple Dinsley estate was sold in 1873, a detailed picture of rents of many cottages at

Preston emerged:

Housing stock at Preston at the turn of the nineteenth century

Holly Cottages, Back Lane

Chequers Cottages

A breakthrough for new housing at Preston in 1913

Even after what appeared to be a positive move to upgrade farm labourers’ cottages, an episode in

1913 illustrated the dilemma which faced local authorities - in this case, at Hitchin, re: Preston.

On 3 March 1913, a long news article headed “The Problem of Rural Housing” reported on a special

meeting of the Hitchin Rural District Council to discuss housing accommodation in the village.

Members met at Preston and inspected the working class housing. Before interviewing the residents,

their opinion was that ‘good, substantial, sanitary houses were urgently required’, that the ‘community

was very inadequately provided for’ and that if better cottages were available, they were confident

‘they would be readily taken up’.

A site was identified along Chequers Lane in a ’good central position’ and with a frontage to the road

of 240 feet, a depth of about 400 feet and containing 2¼ acres. After discussing the possibility of

building eight, six or five cottages, the financial implications were debated.

Each cottage would cost £150 to build. If six were built, the total cost would be £1,000. The annual

balance sheet looked like this:

Receipts:

Rental at 3/6d a week £54 12s 0d

less allowance for vacancies 1 7s 6d

Total 53 4s 6d

Outlays:

Repayment of interest at 4% on £1,000 £40

Repairs and insurance 9

Rates and taxes 6

Collection of rents etc 1 17s 6d

Total 56 17s 6d

The proposal was not self-supporting as there would be an annual deficit of £3 3s 0d which would

have to be funded from the total rates collected by the local authority. Despite this, the duty of the

Council to provide adequate housing was paramount. The existing cottages at Preston were ‘more or

less insanitary and lamentably deficient in accommodation for the present population’ and

overcrowded. Building the new homes would partly stem the flow of the rural population to towns.

The recommendation was to buy the whole plot from Mr Pugh for £160 and build six houses on it to be

let to Preston families. A debate about the rent ensued as there would probably be more than one

wage earner in the households. One speaker thought that the project would kill private enterprise,

adding that the main reason why there were insufficient cottages in rural areas was that land could not

be bought at a reasonable price. Another said it was because of the failure of private enterprise that

there was a gap in housing accommodation.

It was also stated that the de-population of rural districts was the most serious matter that they had to

face. However, young men couldn’t marry because they couldn’t find accommodation. They moved to

towns (partly to enjoy ‘town life’), which became overpopulated, or moved to Canada or Australia. A

Miss Seebohm added “they had had the difficulty of Preston people coming to live at Hitchin”.

In the event (and ironically, in view of some of the comments noted above), private local landowners

stepped in to improve the housing stock in the village. In September 1913, RJW Dawson wrote to

Council suggesting that Mr Fenwick of Temple Dinsley build six cottages on the site to save the

expense (to the Council) and to ensure people would be getting better houses. It was noted that since

the inquiry at Preston, two new cottages had been erected and would shortly be ready for occupation

and that Mr Fenwick Harrison intended to build seven cottages for men who worked on his Kings

Walden estate and lived at Preston (these were Holly Cottages at Back Lane). So, incredibly, fifteen

new cottages were planned for the village. A month later, Fenwick’s guaranteed his offer for the six

cottages to be built with a rent at the proposed rate of 3/6d a week - although he asked for the land

then in the possession of the Council to be made over to him.

And so Chequers Cottages were built.

One cannot help but contrast this state of affairs with what has happened to Preston housing stock

since 1925. Although more council houses were built at Chequers Lane as well as the Swedish

Houses which were assembled there, and bungalows have been erected at Templar’s Lane, most of

the new-builds have been detached homes.

Preston has now become a desirable place to live. This is reflected by the price of houses in the

parish. One of the oldest-standing homes, Reeves Cottage (where my parents lived with their young

son for a few years when Dad was a labourer at Preston Hill Farm) was sold for one million pounds in

2019. Six new affordable homes were built in the village during 2015 and a further six dwellings were

incorporated into the site of the former Dower House/The Cottage in 2020/21.