Back Street Independent Meeting House, Hitchin

What distinguished the Independents or Congregationalists from other Non-conformist churches? The

clues are in the name – each congregation was independent, submitting to the rule of Christ rather

than to the authority of ranks of men. The congregation shunned the hierarchy of the Anglican Church

with its deacons and bishops.

But the strength of the Independents could also be their Achilles heel - although there were checks

and balances in the chapels, the personality and inclinations of the pastor could attract or disperse

the flock. The histories of each chapel are also often dominated by the ostracizing of sinners for

misdemeanours such as intemperance and immorality.

The Hitchin Independents

Towards the middle of the seventeenth century, the Lord of Hitchin Manor was Samuel Chidley. His

mother, Katherine (who stayed occasionally at Hitchin) wrote a pamphlet, The Justification of the

Independent Churches of Christ. Its thrust was that the administration of congregations should rest

with Christ and she dismissed the ‘rabble’ of priests, bishops and deans. She also criticized the

trappings of the established church – its altars, images and ceremonies.

There were hundreds of Independents at Hitchin during the Civil War (1642 – 1649) – indeed, they

ruled Cromwell’s army. At the time, the Independents of Hitchin were part of the same broad church

as the Baptists. However, they separated from their brethren in 1677 in a reaction to a newly –

appointed Baptist pastor.

Ten years later, they joined the congregation of Independents at Hertford, sixteen miles away. On

Sundays, they walked or rode there from Hitchin unless there was the occasional meeting at half-way

Bradbury End. Hitchin hosted a combined service once a month. In a newly-found, perhaps self-

serving spirit of harmony with the Baptists, the Independents asked that they might use a Baptist barn

at Hitchin for their gatherings. This accord was somewhat predictably of brief duration as the

Independents sought to seduce some Baptists to their cause.

So, homeless for three years, the Independents met at Preston: in summertime on the Green (aptly

known then as Cromwell’s Green) and, in winter, at the Widow Heath’s home (which had been

licensed for services in 1672). They also held meetings in the farmhouse of John Harper at

Maidencroft (Ippollitts).

The Independent Meeting House at Back Street, Hitchin

In 1690, the congregation decided it was time to have a chapel to call their own at Hitchin and bought

a plot of in Dead Street (later known as Back Street and now Queen Street). The first meeting in their

new spiritual home (shown above) was held on 27 April.

Three years later, an extraordinary event stirred interest in the fledgling chapel. A young shepherd

from Offley, David Wright, had been afflicted by running sores and ulcers (scrofula) so that he could

walk only with crutches. A condition for his employment was that he should attend the Meeting Place

with his farmer-employer, Mrs Dermer. Wright struggled to the chapel and sat in the gallery,

exhausted. Hearing of a miraculous healing by Jesus and, inspired, he leapt up crying out, ‘I believe

and am cured body and soul’. His sores were now scars and his crutches were banished. The

‘miracle’ was confirmed by the sons of Mrs Dermer and his workmates.

This episode was manna from heaven and provided the impetus needed for the Hitchin Independents

to leave their Hertford friends and establish their own church. But when William Terry was appointed

their pastor in 1694, cumulus clouds of doctrinal conflict loomed. There were disputes over the value

of the sacrament and the validity of infant baptism. The resulting schism ended with 47 members of

the flock returning to the Hertford congregation, including five members from Preston and four from

Ippollitts. The divide between the congregations widened in 1707 when the Hertford pastor took it

upon himself to cut-off members of the Hitchin chapel including a Mary Gutteridge for ‘fornication and

other ill carriage’. Eventually, in 1715, the Hitchin exiles returned to the fold.

More upset lay ahead. A new pastor, William Brown, allowed ‘himself to be overcome with liquor’ and,

after a long, painful ‘descent into degradation’, Brown was ostracized. The chapel now had no pastor

and its numbers had lapsed to 67 when a new minister was appointed in 1729, Joseph Pitts. His

brand of service resulted in a three-fold increase of the flock. However, the next decades saw a

succession of pastors whose methods divided or united the congregation and the turmoil was

heightened by a rash of ousting of members.

A view of the Back Street Meeting House Sunday School and main congregation circa 1800

Around 1800 the Hitchin Independents appointed two Welsh pastors. The second, William Williams,

showed a more merciful stance towards his sheep and, during seven years, only one was separated

from the flock.

Following a stroke in 1812, Williams was succeeded by Charles Sloper who ruffled fleeces and

several, including Williams’ widow and two deacons, left for greener pastures. Sloper appealed less

to the respectable and more to common folk. He converted a barn at Trunks House, near Minsden

Chapel, into a Meeting House but his deacons revolted against his authority and he eventually died of

a broken heart in 1822.

Congregation numbers ebbed and flowed, the Back Street Meeting House gradually decayed until it

was replaced by a new chapel in 1855. It was built ‘in the Italian style of architecture’ with an organ of

Grecian design – both choices deliberately at odds with mainstream Christian traditions.

The congregation grew steadily and the cases of discipline decreased. And so the Hitchin

Independents were found in the twentieth century, when their main, uncontroversial concerns were

the ‘squealing organ’ and the condition of the urns.

The following poem (‘the artless rhymes’ of William Carter) may convey something of the ambience

within the Meeting Place:

Far back from the street stood the Meeting House old,

Where garden and fence did its entrance enfold,

A square, massive building with well-buttressed walls,

With a double-spanned roof to resist the rainfalls.

On its southerly side was the graveyard—so dear,

Where on Sundays were gathered from far and from near

An assemblage of people who lingered and gazed

On the moss-covered tombstones their forefathers raised.

But let me but faintly attempt to describe

The old Meeting House as seen from inside,

With its high wooden pews, where, lost to sight

Of parson and people you could slumber outright,

And in snug little corners, where quality sat,

They could, if they chose, even quietly chat,

For a curtain of baize would shut them quite in,

And like to a cloak would cover their sin.

Tall pillars supported the roof, that was high,

The pulpit, 'twixt windows that looked on the sky,

Was fixed to the wall up a long winding stair,

Which needed a climb ere you found yourself there.

And just at its front was the table-pew found,

Allotted to elderly men who sat round

A table on which, as their elbows they placed,

With earnest attention the preacher they faced.

To add to its comfort a stove was supplied,

With a long pipe to carry the smoke to the side,

And pleasant it was on a cold frosty day,

If your seat chanced to be very near that way.

Round three sides of the building the gallery ran,

Which I'll try to describe, if I possibly can.

There facing the preacher were organ and choir -

They were close to the ceiling and could not be higher

Grave men and women, maidens and boys,

All joined in the singing, producing a noise

Which, if not melodious, did certainly raise

The services louder in song and in praise.

The clerk read the hymns out, a verse at a time,

Then singers and people would heartily join;

And good old tunes we can never forget

To the choicest of hymns were invariably set.

At one end of the building, were vestry and room

Where friends met for prayer and would welcome you soon,

There tea meetings often enlivened the scene,

Those were happiest days that have ever been seen.

But they have all gone, with faces we knew,

Those men of the past who to conscience were true.

The Meeting House, too, is a thing of the past,

Like things of the earth that are not meant to last '

This article has spotlighted Preston’s association with the Independents. The religious spirit of

independence manifested by Preston folk has already been commented on – probably provoked by

the lack of a local chapel of ease and the high-handed attitude of the clergy of St Marys, Hitchin in

1688 (See Links: Preston and religion; Conflict with St Mary’s).

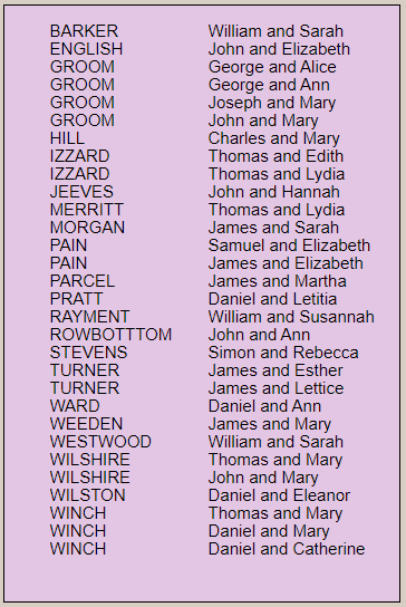

The birth and baptismal records of Back Street (thanks to their adherence to the doctrine of infant

baptism!) have the welcome notes of the place of residence of parents so that a list of Preston

worshippers from 1788 - 1837 can be compiled (For a full list of baptisms: Link: Back St baptisms).

They included the following couples: