Almina, Countess of Carnarvon and

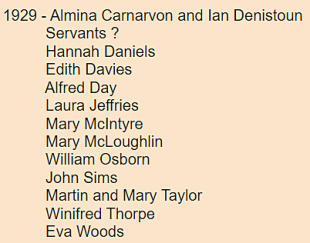

Lt Col Ian Dennestoun at Temple Dinsley 1929 - 1935

Searching for apt adjectives to sum up the lives of Almina, Countess of Carnarvon and

Ian Dennistoun is a challenge. If one is limited to just two, perhaps ‘colourful’ and ‘newsworthy’

vie with several others as the best choices.

Almina had links to the rich Rochchild family - far more than links, actually. After her marriage to

the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, she became the real-life mistress of Downton Abbey (aka Highclere

House) in Hampshire for more than twenty-five years.

During this time, she financed the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamum by Howard Carter,

which grabbed the world’s attention.

After the death of the Earl, she married Ian Dennistoun, who had been rapidly promoted in the

Army, thanks to his first wife’s ‘efforts’. But soon they found themselves embroiled in one of the

most sensational and salacious legal cases of the twentieth century.

They arrived at Temple Dinsley, Preston in late 1929 and stayed intermittently for six years,

during which time it now transpires that Ian pursued an unlikely hobby.

After his death in 1938, Almina struggled to rekindle her recognition by High Society, whilst

fighting a rearguard action against bankruptcy. She died the kind of death she had dreaded.

This is a tale which is difficult to tell because so much has been written about their lives by

people with seemingly different agendas.

The carefree couple in 1925 - when inquisitive and prying eyes were intruding into their lives

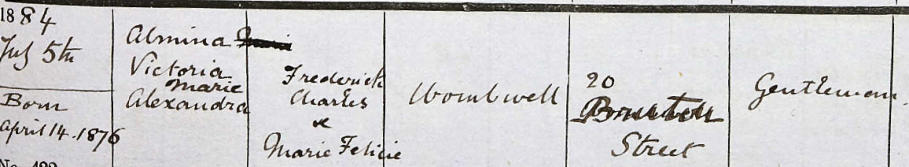

Almina was born at Battersea, London on 14 April 1876, but a smokescreen swirled around her

baptism eight years later on 5 July 1884 at Hanover Chapel, Regent Street, London:

Almina’s (pictured right) mother was Marie Boyer, the daughter of a French

financier from an old aristocratic family. Marie married Frederick Wombwell, a

‘rakish man, stalked by debt’, however, the couple parted eight years before

Almina’s birth.

The true identity of Almina’s father is probably concealed in archives beyond

the public domain. The pool has been muddied by Marie’s friendship with the

wealthy banker, Alfred Rothchild. It has been boldly stated in several books

that he was Almina’s father. He was certainly Almina’s entree to the higher

echelons of Society and was extremely generous to her. After Almina married

Lord Carnarvon, it suited his family to trumpet her Rothchild ancestry. It is

undeniable that Alfred Rothchild was Almina’s father-figure and effectively her

guardian. Under his tutelage, she was presented to Queen Victoria

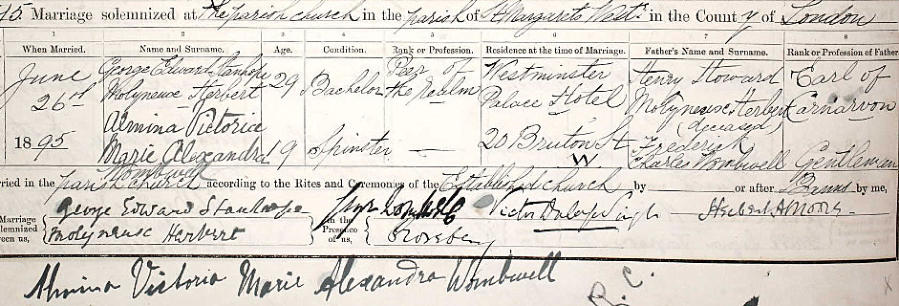

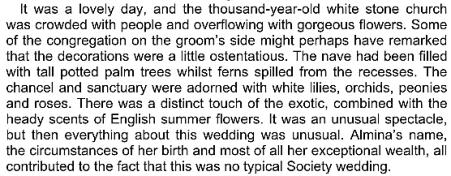

At a Buckingham Palace State Ball, Almina caught the eye of her future husband – the heir to the

Earldom of Carnarvon. His family seat was Highclere Castle, Hampshire and he also owned Bretby

Park in Derbyshire. They married at St Margarets, Westminster on 26 June 1895.

The Earl had signed a marriage contract with Alfred Rothchild and, as a result, Almina was ‘protected

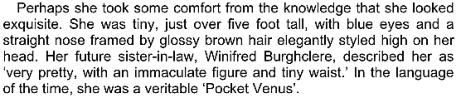

by a level of wealth so stupendous that it could buy respectability and social acceptance’. She entered

the church as an illegitimate child and emerged as the 5th Countess of Carnarvon.

The future Lord Carnarvon was no academic, being lax and lazy, preferring the racing form book. In

1889, he visited Egypt for the first time and developed an interest in ancient art, photography and Cairo

whorehouses and smoking dens. As the fifth Earl of Carnarvon, his title was his prime asset as he

suffered with poor health, a pock-marked complexion and impending insolvency.

When they wed, Almina gained a title; the Earl acquired access to wealth - and so began twenty-two

years of loveless marriage.

The young Almina successfully entertained the

future King Edward VII at Highclere as she

mastered her role as mistress of a country house

and estate. The couple flitted between their

English home and France. In 1898, while visiting

Egypt, Almina became pregnant and gave birth to

a son and heir. She then threw herself into a whirl

with the best of society until a second child, a

daughter, was born in 1901. Meanwhile, the Earl

continued to cultivate his interest in Egyptology. In

1905, he met the former Director of Antiquities at

Cairo Museum, Howard Carter, and for several

years he and Almina visited Egypt. In London,

Almina was consolidating her reputation as a

delicate beauty and loving mother.

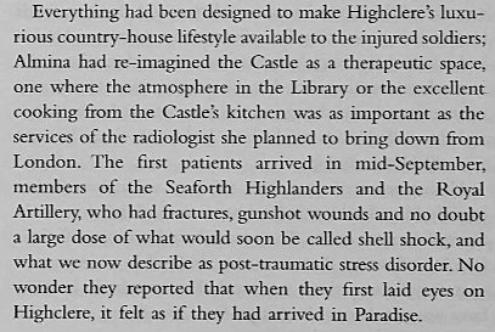

During the First World War, Almina re-invented herself as a Society lady who devoted herself to

caring for the injured in combat – Highclere was transformed into a hospital.

In 1918, Alfred Rothschild died and left a substantial part of his vast estate to Almina. Included was his

magnificent London home with its works of art and furniture which were worth hundreds of thousands

of pounds. The following year, peace having been declared, Almina closed her London hospital. The

Earl used some of their fortune to fund continuing excavations in Egypt.

The creation of a nursing home was a pivotal moment in Amina’s life - it was a template which was to

be used in increasingly less grand surroundings during the rest of her life. After Highclere, she moved

on and opened a new hospital at Bryanston Square, London.

Recuperating patients at Highclere

Administering hospitals and nursing homes is an expensive operation - especially for someone such as

Almina who considered charging patients for the cost of their stay to be bad form. She subsidised her

activities by selling items from her treasure trove of Alfred Rothchild’s estate, perhaps never dreaming

that this ready reservoir of funds would ever dry up.

We are fast approaching the moment when the orbits of Almina and Ian Dennistoun collided, so we will

break away from Almina’s exploits to examine Ian’s life until the early 1920s.

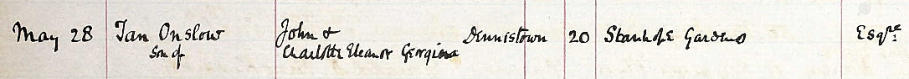

Ian was born on 29 April 1879 and baptised on 28 May 1879 at St Marylebone, Westminster.

His grandfather had been a Member of Parliament and his father,

John Dennistoun (a gentleman of highest commercial standing and

experienced business aptitude), was a merchant banker - a director of

Dennistoun, Cross and Co (est. Glasgow 1790, ‘well-known and

respected) of Threadneedle Street. In 1891, Ian and his family were

living at Horton Lodge, Epsom (right) with an army of servants and

maids. When John died in 1924, his (and Ian’s) address was Stanhope

Gardens, which is a stones-throw from the Natural History Museum in

South Kensington where a two-bed flat sells for £1.1m today.

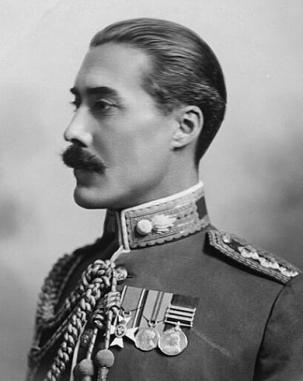

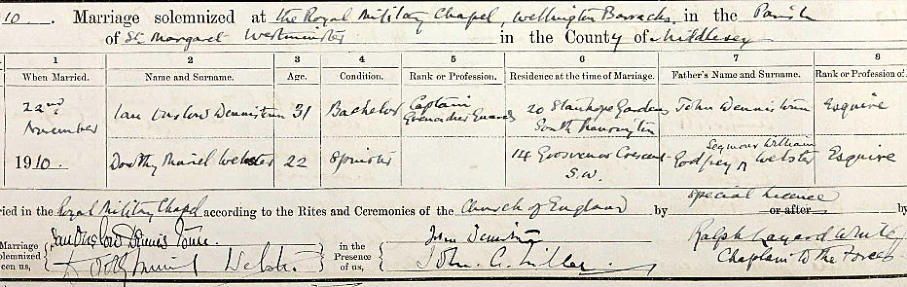

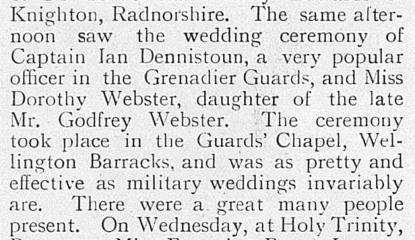

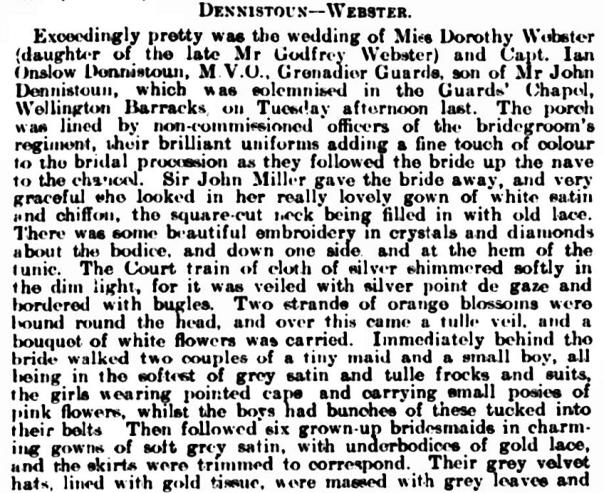

Ian joined the Army in which, aged nineteen, he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant,

3rd Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers in September 1898. Then, he was involved with the Boer War

as a Grenadier Guard. By 1910, Ian was a Captain. He married Dorothy Murial Webster at the Royal

Military Chapel, Wellington Barracks, Westminster on 29 November 1910. The marriage was

announced and reported by The Tatler and other magazines and newspapers, which demonstrates the

social significance of this union.

Queen magazine, which also showed sketches of the

dresses worn.

The Tatler

Ian’s subsequent military career was marked by rapid, some might say ‘improbable’, promotion - Major

in 1915; Lieutenant Colonel in 1919.

However, trouble lay ahead. Ian had broken his hip during war-time, from which he never recovered.

The Dennistoun finances crumbled from a healthy beginning and ‘the couple’ began living separate

lives, each having embarked on several affairs. They divorced in 1921 in Paris to avoid negative

publicity in England and Ian stayed there, scratching a meagre living in the wine trade.

Among Almina and the Earl’s circle of friends was Sir John Cowans, the paymaster-general of the

Army. When Cowans became ill, Almina rushed to his bedside where she first met Dorothy

Dennistoun. The two women became extraordinarily close, Dorothy living with the Carnarvons for

about eighteen months. Almina began to use Ian Dennistoun’s bank account to hide money from the

tax authorities.

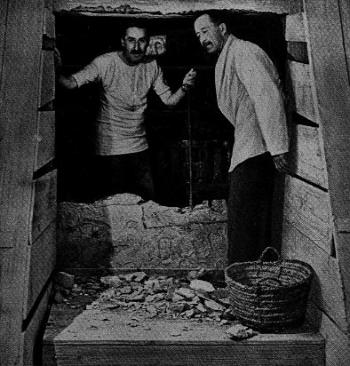

Meanwhile, in Egypt, the Earl’s optimism, Howard Carter’s instincts and Almina’s money hit the

jackpot: they found the tomb of Tutankhamum - ‘golden beds and couches of state, golden caskets,

chariots, candlesticks, furniture, statues, clothes, weapons and a magnificent throne, encrusted with

gold, silver and jewels’.

The Earl of Carnarvon relaxing in Egypt and leaving Highclere to film in Egypt

The Earl and Howard Carter at the entrance of the tomb and some of the glorious treasures

Four months later, in April 1923, the Earl was dead – the victim, some said, of the curse of King Tut

and others, of blood poisoning caused by a mosquito bite. He bequeathed all of his Egyptian relics to

Almina, who announced that she now wished to be known as Almina, Countess of Carnarvon, thus

cementing her place in English society. She also purchased a home in her own right: Alvie Lodge,

Kincraig, Inverness-shire.

Ian Dennistoun, although divorced from Dorothy, met her several times during 1923 and was clearly

still infatuated with her. His situation was complicated as Almina had set him up in an expensive

apartment in the West End of London.

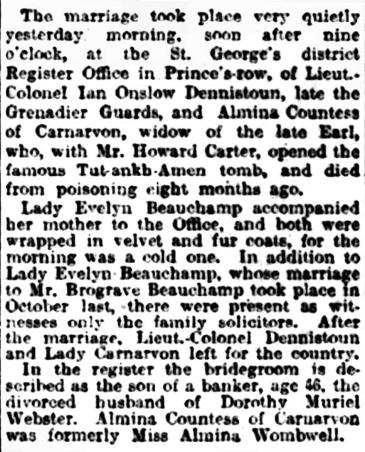

On 19 December 1923, Ian and Almina married at a Registry Office at Princes Row:

Four days later, Dorothy wrote a letter in which she inferred that Almina and Ian had committed

adultery when Lord Carnarvon was alive and demanded that Ian keep his financial promises to her,

using Almina’s fortune. Almina viewed this as an attempt at blackmail.

In 1924, Dorothy issued a writ against Ian claiming £13,000 and a backlog of support promised in

1921. The ensuing Court case, Dennistoun v. Dennistoun, exposed the dirty laundry of all involved. Its

revelations titillated the nation (and many in the USA).

Left, Ian Dennistoun with his counsel;

middle, Dorothy; above, Ian with Almina

It was alleged that Col Dennistoun had encouraged his wife’s liaison with General Cowans in order to

obtain appointments (ie Secretary to the Governor of Jamaica). Mrs Dennistoun was asked, ‘Did you

pay the price?’ Murmured reply, ‘Yes’. She was Cowans’ mistress from 1916 until 1921. Various letters

from Ian were read out in court - ‘O girlie darling, I hate you using that lovely little body of yours as a

gift….it does make me so despise myself…no-one else would have done what you have done and gone

through all you have to make Tiger Boy happy…’. Later, Cowans arranged a promotion for Col

Dennistoun in the Labour Corps in France. He emerged from WW1 with the Victorian Order of the Legion

of Honour and the French Croix de Guerre.

When they married in 1910, Mrs Dennistoun had brought £10K to the marriage, her father paid rent on

their flat and allowed them £800 a year while Mrs Dennistoun also received £250 a year from him. Yet,

by 1912, the couple were in debt. From 1914 to 1916, Mrs Dennistoun was living with her in-laws.

Both alleged that the other had been immoral - Col Dennistoun avowed that his wife had affairs with

seven men, and was pregnant by one of them, Mr Bolin (a Spaniard), when they divorced.

Further details about Col Dennistoun came to light. He had a problem with sciatica during the trial, being

absent one day and limping badly, leaning on his stick on another. He was penniless in 1920/21. When

Almina first saw him, she described him as ‘the thinnest, most emaciated creature possible’. Around the

time of their marriage, Almina gave Col Dennistoun a total of £90K which was raised by the sale of some

of the works of art that Alfred Rothchild had left her. He had spent more than £40K in the second half of

1923.

The jury decided that Mrs Dennistoun should receive £5K damages, but this was over-ruled by the

judge. He granted Mrs Dennistoun only £472 18/-, with respect to amounts she had given Col

Dennistoun. The two protagonists were left to settle their legal bills which were estimated to be between

£30K - £40K.

The King of England wrote to the Lord Chancellor of his “disgust and shame” about the proceedings. As

a consequence of this court case, in 1926, Parliament passed the Judicial Proceedings (Regulation of

Reports) Act prohibiting the detailed reporting of divorce cases in newspapers.

It seems appropriate at this juncture to assess Ian Dennistoun’s character. As a man who pimped his

wife, he was viewed as weak-willed and a ‘chancer’. The following published comments are offered,

with the caution that their writers may be biased:

Ian was featured in a book titled, Military Misdemeanors: Corruption, Incompetence, Lust and

Downright Stupidity and also selected as a subject in the book, The Lives of the English Rakes.

There was one additional repercussion for Almina during these

tumultuous years in the ‘Roaring Twenties’ that is pertinent to our

study because relations between Almina and her son, the new Earl

of Carnarvon had become frosty.

He disapproved of his mother selling so much of her inherited wealth

and also her quick and unseemly marriage to Ian. Indeed, he didn’t

attend his mother’s re-marriage. By the terms of his father’s will, he

was the new master of Highclere. Almina had to find a new home for

herself and Ian.

Ian had lost his army commission and ‘retained no rank’. Several of Almina’s friends severed their links

and she squandered part of her inheritance to pay for the litigation. She and Ian retreated to Alvie in

Scotland to lick their wounds and sold more of Alfred’s legacy at Christies. By 1927, a new idea for

self-promotion was hatched - Almina decided to open another nursing home, Alfred House, at Portland

Street, London. It was funded by the sale of some Egyptian antiquities and her Alvie estate. This

philanthropy went some way to restoring her reputation in Society.

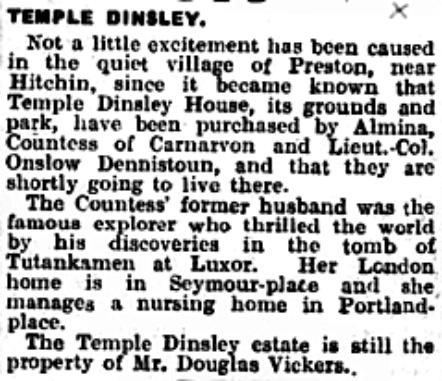

In 1929, it was decided, for the sake of her husband’s health that the couple would move to Temple

Dinsley at Preston, Herts. On 12 December 1929, The Times announced that the couple had ‘arrived

at Temple Dinsley, Hitchin, which is now their permanent address’.

December 1929

This paragraph explains why the couple moved to Temple Dinsley - but the house is not mentioned,

which is curious. The Wikipedia entry for Almina also doesn’t include Temple Dinsley, although they

owned the mansion for six of their fifteen years together. Perhaps chroniclers only found references to

them living in London - and it is a fact that they were often absent from Preston.

While the villagers were excited about the new arrivals, this didn’t prevent an early clash. The Preston

Scrapbook states, “The Countess of Carnarvon bought the house and part of the grounds around it

from Mr. Vickers. Her interests lay chiefly elsewhere, but her husband Colonel Dennistoun did much for

Preston. She greatly frightened the people of Preston by asking them to help mount some of the

Tutankhamen relics on black velvet, a request which met with a complete refusal.” Daisy in the Broom

adds that Almina ‘brought mummies with them from the pyramids, which villagers, either squeamish or

superstitious, refused to help unwrap.’

In 1930, Ian was appointed as Parish Council representative on Board of Managers, replacing the

departed Mrs Vickers.

It’s easier to chart where the couple were, rather than when they were at Preston between 1929 and

1935 (when they left) and then one may draw one’s own conclusions.

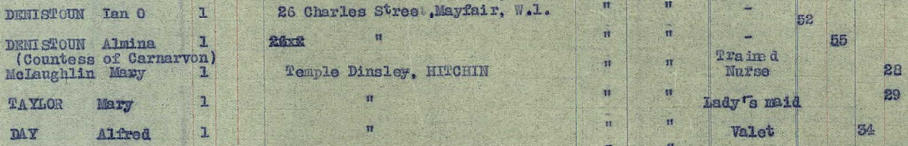

Firstly, from the 1930 electoral

register, the composition of the

Temple Dinsley household:

On 22 January 1932, Ian and Almina together with three servants left Southampton on a cruise to the

West Indies on the Duchess of Richmond. They had returned to London by 11 March:

In late December 1929, Ian was at a hunt at Broadwater, Herts. In January 1930,

Almina attended a ‘When We Were Young’ Ball at the Savoy Hotel and then the

Bucks County Farmers Invitation Ball. In April 1930, Almina and Ian travelled once

more to Egypt, but this year saw the end of her involvement with Egyptology. In

July she attended a cinema matinee at Teddington, London; an ‘at home’ in

London; a ball at Claridges; sold French clocks at Christies and held a garden

party at Temple Dinsley for 250 visiting Bradford Liberals. In October, she was at a

dress show at Tiziana’s. On each occasion, neither was accompanied by their

partner. In 1931, Almina attended a Society wedding at St Margarets, Westminster

in April and a luncheon/tea dance for 300 guests on board Empress of Britain at

Southampton in May.

Almina in 1932

In April 1932, Almina attended a funeral at Sloane Street, London; a wedding at St Margaret’s,

Westminster and, in July, gave a reception in London for the Duchess of Aosta.

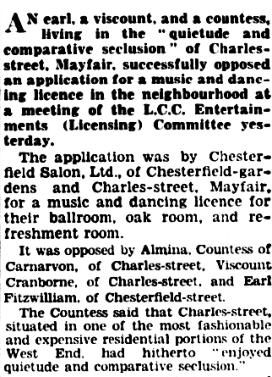

By 1933, Almina and Ian were living at 23 Charles Street, Mayfair

when Almina opposed an application for a licence (see right) in

January. I note that Douglas Vickers and his family were living a few

doors further down the street at No 18b.

Almina attended a garden party in July 1933 at Glynde, Sussex,

which was thrown by the Earl of Warwick. Her gift was a Georgian

tray. In that same month, she was a guest at a ‘congregation of

celebrities’ wedding at Eaton Square.

In September, she was among the throng at the funeral of a popular

sportsman at Lambourne.

In July 1934, both Ian and Almina held a dinner party at the Ritz Hotel

to which many of the gentry were invited.

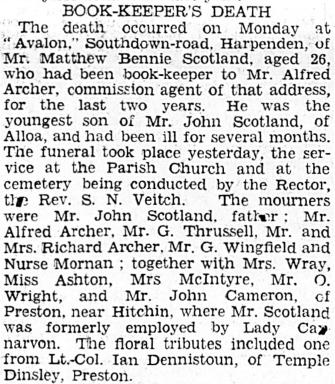

During the preceding month, the following news item appeared:

So, Ian spared a thought for someone who had been employed by his wife. The Preston folk

mentioned were Miss Ashton (daughter of the village baker), Mrs McIntyre (who was part of the

Dennistoun’s retinue and John Cameron, who was living at The Cottage, Preston in 1930. The surprise

for me is that a Mrs Wray is mentioned as one of the Preston people who attended Mr Scotland’s

funeral. My first thought was that she may have been my grandmother - but it was unlikely that she

would have travelled to Harpenden without a member of her family. On further reflection, I believe she

was my uncle Frank Wray’s wife, Margaret, who, like Mr Scotland, was from Scotland and worked as a

housemaid for Mr Vickers at Temple Dinsley. Also at Preston in 1934, on 29 June, Jean Georgina

Clare Dennistoun (aged 16 hours) was buried at St Martin’s. William Cross has established that Jean

was the daughter of one of Ian Dennistoun’s cousins who died at the London nursing home.

How had Ian been occupying his time when Almina was in Town? The answer is perhaps surprising.

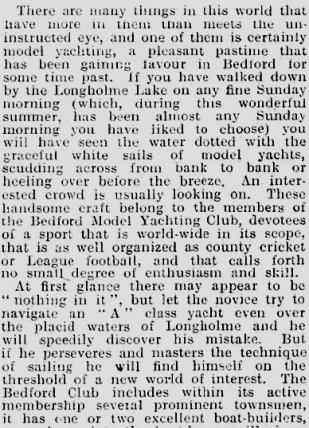

The hobby of sailing and racing model yachts was popular in the second half of the nineteenth century

into the twentieth century not only in Britain, but also in America. This is a typical scene in Central

Park, New York even today:

Before WW2, a race was likely of two legs on a suitable body of water. Boats were carefully set-up,

maybe using mechanical contraptions linking sails and rudder to make the most of the prevailing

conditions - adjustments could not be made after the yachts were floated. In those days, there was

little or no radio control. The setting of the steering gear and sheet positions had to be adapted to the

wind conditions - and this is a subtle art to master. This attention to detail, and the design of the

yachts was the winning formula. Among model yachtsmen the designing and the construction of the

boats was as important and interesting a part of the sport as the actual sailing. These hobbyists were

innovative, scientific and competitive. And, of course, they had their own monthly magazine.

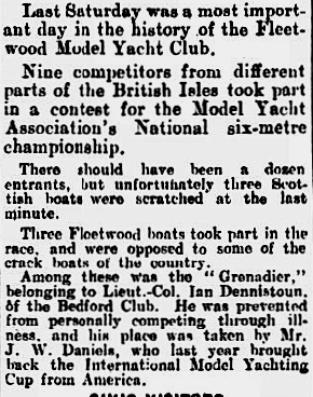

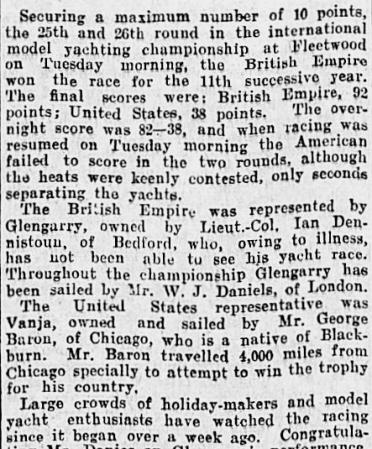

After moving to Preston, Ian became closely involved with the Bedford Model Yacht Club which was

the closest Yacht Club to Preston. In September 1932, from Fleetwood, Lancashire there was the first

public intimation of Ian’s interest in the sport:

It is clear from this report that Ian was not a well man. On several occasions he was unable to attend

events. Instead of experiencing the pleasure of sailing the yachts that he owned and designed, he

entrusted this to JW Daniels, who later wrote a book about building and sailing model yachts. Over

the next few years, Ian entered several boats in events: Grenadier, Glengarry, Fusilier, Lochness and

Plover. As Ian was racing at this level, this probably had been a hobby for some years.

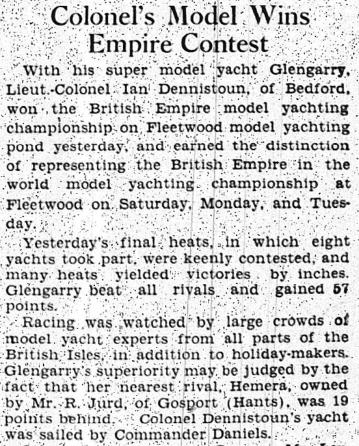

In 1933, it transpired that Ian was President of Bedford Model Yacht Club and a generous patron.

4 August 1933

9 August 1933

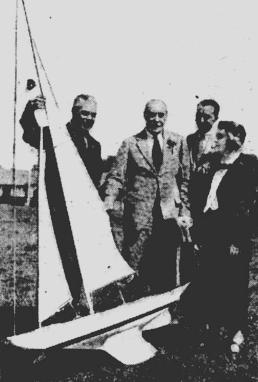

Following this notable success, the Bedfordshire Times carried a keynote article about the Bedford

Club and yacht racing, together with a photograph of Ian and Almina with the winning yacht.

Ian’s successes continued in 1934, although he resigned the Presidency of the Model Yacht Club:

4 August 1934

9 August 1934

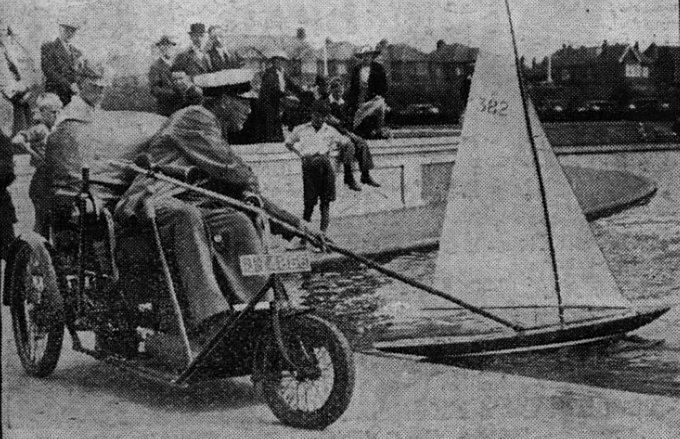

Ian sails his yacht from a bath chair, “being an invalid”

1935 was another successful year, but the pinnacle of Ian’s achievements came in 1936 when, after

another win, the Model Yacht Association selected his yacht Fusilier to represent them at the Olympic

Games. The British team won the six-metre model yacht competition, beating Norway by one point.

So, during Ian’s sojourn at Temple Dinsley, he was occupied designing and sailing model yachts and in

frequent contact with the Bedford Yacht Club. One wonders whether he sailed yachts on the large

pond or the pool beside the mansion.

Looking back, the Dennistoun’s departure from Temple Dinsley was inevitable. Almina was

concentrating on retaining her social position and administering her nursing home. A cartoonist

described it as ‘the immensely chic but slightly wayward nursing home run by Almina’ – she was

running a discreet abortion service! Life at Preston, when he was often alone, was probably tedious for

Ian - and his health was obviously deteriorating. They finally broke all ties with Temple Dinsley when

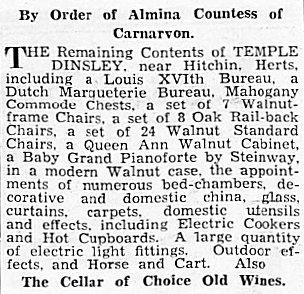

they sold some of their possessions there in June 1935:

On 29 June 1935, this announcement was

made:

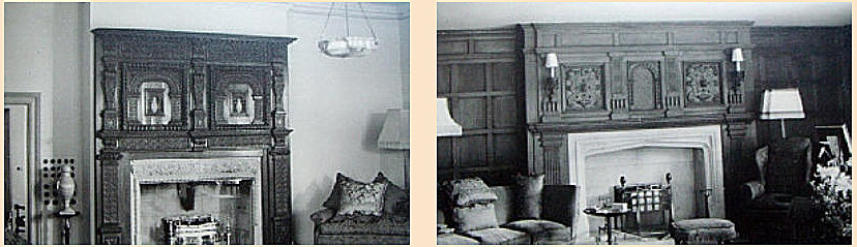

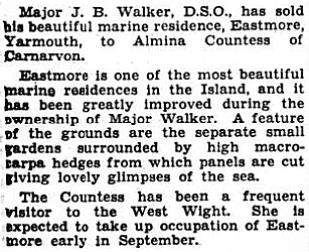

Almina and Ian moved to Eastmore, a property on the west side of the Isle of Wight between Yarmouth

and Bouldnor, for its healthy sea air, however they retained some memories of Temple Dinsley as two

of its fireplaces were dismantled and installed in their new home.

Almina attended a Society wedding at Westminster Abbey in May 1938, but in the middle of the month

Ian fell ill and died at her Portland Place nursing home on 22 May.

Less than a year later, Almina sold up, moved from the Isle of Wight and took

a lease at Regent’s Park, London. The burden of running Alfred House

necessitated another sale at Christie’s and she also sold her interest in Alfred

Rothchild’s £500,000 fund.

The threat of German bombs during the Second World War, led to Alfred

House being closed and then destroyed in 1940. Almina opened a new, small

hospital at Hove, Sussex but this too was deemed to be in the firing line so

she moved on to The Glebe, Barnet, Herts., which became her latest nursing

venture.

She also retained the lease on her London house where, in 1942, she set up

home with James Timothy Stocking (JTS) who, although almost thirty years

her junior, was Almina’s latest beau. He was to be her constant companion for

twenty years though their relationship was concealed from even her closest

family. Once again, Almina’s creditors pressed and she left Regents Park. She

lacked skill in the financial management of her nursing homes having no

reliable accounting system. She considered it bad form to send bills for her

less affluent patients.

Finally, The Glebe closed as she had run out of money. Almina headed for the

Quantock Hills in Somerset, to a thatched cottage near Taunton with an

orchard of six acres. Her plan was to start a market garden run by JTS. It

made a continual loss. Despite this, she borrowed £5,250 from her son, the

6th Earl of Carnarvon and tried to live on her annual allowance of £6,500. But her life was hum-drum

and tedious. To escape, she travelled to London most weeks attending several functions but repulsed

attempts from her circle to visit her in Somerset.

In 1948, Almina’s spend-thrift lifestyle caught up with her. She had sweet-talked loans from a bank

where she had also run up an overdraft. To settle, she sold the cottage, but failed to repay the loan

from her son. He furiously accused his mother of being a scheming swindler and issued a writ for the

monies owed.

Almina and her household moved to a farm near Minehead, Somerset where the descending cycle into

debt continued. She had spent a king’s ransom but now faced total ruin. The tax man hovered, alerted

by her son. He claimed unpaid tax of £22,000 – her liabilities amounted to more than £30,000. The

proud Almina was bankrupt. She called in favours and leased a cottage at Cleeve. Her contemporaries

died or hurtfully shunned her when she appeared at old haunts. Almina was allowed £60 a month on

which to live and in 1954 her grandson was persuaded to buy her 19 Hampton Road, Bristol – a three-

bedroomed home in a row of Victorian terraced houses.

For about ten years Almina cadged money from her family for holidays to the South of France, but her

time was often spent at home gossiping on the telephone. There was also the occasional visit to the

races. JTS was found dead in bed after a heart attack in 1963. In his will he left £500 to Almina’s

housekeeper, Anne – he had been cheating on Almina, and had also seduced Anne’s sister.

In April 1969, Almina, aged 93, (who dreaded swallowing fish and chicken bones) choked on a piece of

gristle in a home-made chicken stew. It couldn’t be dislodged so her lower esophagus was removed.

She lingered for three weeks until her death.

William Cross’ appraisal of Almina: She led a tumultuous life – striving for ‘more money, more

status, more happiness’. It was ‘a fulfilling life when things went her way, especially when she was

nursing’ but she ‘plunged herself into doomed situations and relationships....Money had a way of

slipping through her fingers...She was strong-willed, resilient..delighting in surrounding herself with

notable figures...mostly men, for she loved men...She had genuine feelings for some members of her

family but was unable to commit to them beneath the surface...She was, despite her faults, a very

great lady, a strong-willed old world aristocrat, a Countess through-and-through’.

Acknowledgement: sections of this article have been distilled from William Cross’ book, ‘The Life

and Secrets of Almina Carnarvon’. I am also grateful to him for supplying the photographs of

the Temple Dinsley fireplaces and for allowing the other photographs shown above to be used.

They are from the collection of Tony Leadbetter, Almina’s godson.

1945

1930

Mud

In retrospect, this earlier event in the village was the final one with which the Dennistouns were

involved: